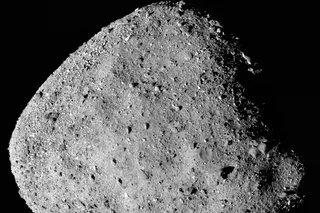

Comet 67P looks little like the illustration created by the European Space Agency before Rosetta's arrival. Reality is far stranger. (Credit: ESA–C. Carreau/Rosetta-Navcam) There is a cliche you hear all the time when scientists describe their experiments: "We expect the unexpected," or its jokier cousin, "If we knew what we were doing it wouldn't be called research." (That second one is often, but dubiously, attributed to Albert Einstein.) But like many cliches, this one is built on a foundation of truth--as the comet explorations by the Rosetta spacecraft and Philae lander keep reminding us. The latest shocks come from the huge batch of science results released last week, but the Rosetta mission has been a series of surprises going all the way back to its origins. And with another 11 months of exploring to go (the nominal mission runs to December 31) , it is safe to say that the ...

Rosetta, the Comet, and the Science of Surprise

Unlock the mysteries of Comet 67P exploration as Rosetta and Philae reveal unexpected scientific results and surprises.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe