October 2022 Places

Trinity Site: White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico 505-678-1134

The National Atomic Museum Albuquerque, New Mexico

Twice a year the pilgrims come, thousands of them, to the remote New Mexican desert that early Spanish settlers called La Jornada del Muerto—The Journey of the Dead. Long caravans of cars snake across the land where hunger, thirst, and Apaches were once killed without mercy. There's a solemnity to the procession as if the desert were enforcing its own silence and gravity upon the travelers. All are drawn to one of the most haunting places on Earth, where more than a half-century ago an elite group of scientists working on the top-secret Manhattan Project unleashed a weapon that melted more than three square miles of desert sand into barren glass.

The place is named Trinity. Here, on July 16, 1945, at 5:29:45 a.m. mountain time, the world's first atomic bomb exploded, creating a false dawn in skies as far away as Albuquerque, 100 miles to the north. These days you no longer need top-secret clearance to visit. Anyone can come, although the trip requires careful planning. Trinity lies on the White Sands Missile Range, where weapons are still actively tested, and opens to the public only on the first Saturday in October, as well as the first Saturday in April.

Ground zero, where the bomb was detonated, is just a few hundred yards beyond a visitor's parking lot. I set out on foot with dozens of other pilgrims; our conversations dwindle, then cease, as we approach a zone where imagination fails. Nothing spectacular awaits our eyes. But the sheer history of the place weighs upon us.

Here, where we stand, temperatures once soared to tens of millions of degrees, hundreds of times hotter than the sun's surface, marking a horribly bright beginning to a dark new period in history. Here the first terrible atomic mushroom cloud appeared. The weapon Manhattan Project physicists dubbed "the gadget" blasted out a crater almost 1,200 feet across and up to 10 feet deep. Years of erosion have left only a large, shallow depression, and a chain-link fence now surrounds a 400-foot-wide central area from which the radioactive debris was removed long ago.

An obelisk of black volcanic rock marks ground zero's exact location. Nearby, some stubby, twisted iron rods that are just a few inches from the earth are all that remain of a 100-foot-tall tower from which the first atomic bomb was suspended. It was detonated above ground to simulate the effects of the aerial blast planned for Japan. Most of the tower disintegrated instantly. The iron nubs survive only because they were below ground at the time of the explosion, encased in thick concrete blocks.

Photos depicting the history of the Manhattan Project hang from the chain-link fence around the crater. Today, as 500 people contemplate the photos, the weather looks much as it did that summer morning 57 years ago: a deep blue New Mexican sky, feathered with a few high cirrus clouds. Several of us stare at one photo. It shows a gaunt, almost spectral Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist who led the effort to create the first atomic bomb. He is at ground zero, wearing a fedora, suit, and tie about two months after the test. Some military officials stand with him; all are grim-faced, gazing at the twisted remains of the test tower as though standing above a grave site.

A sense of unease still permeates the air here and serves as a reminder that the Manhattan Project never really ended. By today's standards, the bomb that exploded at Trinity was a small, ineffectual thing. We now have far more terrible weapons. You can see some of them for yourself at an unusual museum just two hours to the north that, unlike Trinity, is open year-round.

For security reasons, the National Atomic Museum moved after September 11 from Kirtland Air Force Base, just south of Albuquerque, to new quarters on a quiet side street near the city's Spanish colonial Old Town. Its displays are informative, often sobering. Illustrations and photographs trace the history of atomic physics, from the first insightful speculations of the ancient Greeks to the race to build the bomb during the Second World War. There are copies of correspondence between Albert Einstein and President Roosevelt and accounts of how more than 1,000 rural families were displaced in Tennessee and three towns demolished in Washington to make room for uranium and plutonium processing plants.

Most fascinating of all are the museum's full-size replicas of bombs and warheads, as well as unarmed versions of actual weapons, including the upper three stages of a Trident I missile. The submarine-launched missile carries eight independently targetable 100-kiloton warheads, each able to destroy a city, and navigates by the stars, which it can see even in daylight. The protective nose cone, I'm surprised to learn, is made not of some high-tech alloy but mostly of Sitka spruce, which, because it doesn't conduct electricity, better protects the missile's circuitry.

The weapons arrayed here embody a fierce amount of killing power, a fact the museum does not shy from. Prominently displayed is a quote from the Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard, who worked on the Manhattan Project: "A nation which sets the precedent of using these newly liberated forces of nature for purposes of destruction may have to bear the responsibility of opening the door to an era of destruction on an unimaginable scale."

October 2022 Science Fashion

Bug Apparel Neckties, $24.95-$39.95 Scarves, $24.95-$39.95 Boxers, $15-$19.95

A new fashion trend is catching on in The age of anthrax anxiety: germ wear. A line of silk ties from Infectious Awareables (www.iawareables.com) features magnified images of anthrax and various other microscopic subjects of biomedical research such as (A) malaria, (B) neuronal cells, and (C) the Ebola virus. Additional designs in the collection include cholera, tuberculosis, and rhinovirus (the common cold). Roger Freeman, who takes the colorful images off slides or micrographs from the Centers for Disease Control and other labs, donates 5 percent of his company's profits to disease research and prevention and includes a "learning note" on the reverse side of each tie.

Behind the swarms of disfigured red blood cells on Freeman's personal favorite—the malaria tie—the note reads: "Malaria kills nearly 2 million people every year, and is becoming increasingly resistant to treatment." Infectious Awareables also sells scarves and boxer shorts, which sport gonorrhea, plague, and testosterone designs, and plans to introduce greeting cards, dubbed Bionoteables, in time for the coming holiday season. However, Freeman won't include his anthrax design in the first batch of cards. It's a bit too soon to be sending that particular virus—in any form—through the U.S. mail. — Lauren Gravitz

Photograph by Jens Mortensen

October 2022 Books

Darwin at Downe Tracing the fitful origins of the theory of evolution

By Bruce Stutz

Charles Darwin: The Power of Place By Janet Browne Knopf, $37.50

Charles Darwin: Voyaging, the first installment of Janet Browne's epic biography, chronicled the coming-of-age of a member of the Cambridge sporting set who caroused, rode, hunted, and, by his own account, "sometimes drank too much, with jolly singing and playing at cards." Browne recounted Darwin's transformation during his five-year expedition in the 1830s aboard the HMS Beagle from something of a wastrel into a naturalist with a penchant for tireless exploration, specimen collecting, and original analysis.

Darwin emerges in this second and final volume of Browne's biography as a man transformed yet again—this time into a settled country gentleman of Downe, a village just beyond the suburbs of London. He is married with eight children and struggling more than two decades after the voyage of the Beagle with an unfinished manuscript, "a great pile of paper on his study table that he ruefully called his 'big book on species.'"

Photograph by Jens Mortensen

Over the years, Darwin cloisters himself behind bulwarks of wealth, family, and friends, these last including the best liberal scientific minds of Victorian England: the geologist Charles Lyell, the botanist Joseph Hooker, and the eminent biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, who becomes one of Darwin's most staunch and effective proponents.

Together they cajole him to complete his monumental treatise, though Darwin himself leans toward the life of a dilettante naturalist, collecting specimens, puttering in his garden, and dithering with his microscope. Ensconced in Downe, he seems destined not to rise above the legacy of his grandfather Erasmus, a prominent physician, or surpass the expectations of his overbearing father, who once told him: "You care for nothing but shooting, dogs, and rat-catching, and you will be a disgrace to yourself and all your family."

What finally jolts Darwin out of his languor is a thin package that arrives at his door one morning in June 1858. It is from Alfred Russel Wallace, a field naturalist traveling through the Dutch East Indies. A year before, Darwin had asked Wallace to send him some skins of Malayan poultry. "But the package contained nothing of the sort," writes Browne. "Although Wallace's words were unassuming and polite enough, they had acataclysmic effect. . . . What the packet enclosed was a short handwritten essay which, line by line, spelled out virtually the same theory of evolution by natural selection that Darwin believed was his alone."

Here Browne traces the odyssey of Darwin's great work, On the Origin of Species, the impact of his subsequent writings, and the accompanying storm of controversy. The genius of Browne's book is that she sequesters us in Downe with Darwin—the dyspeptic general in his bunker, marshaling his troops against the scientific and ecclesiastical establishments. He writes thousands of letters, goading his detractors and urging on his defenders, all the while maintaining his positions with little compromise. From Darwin's compound, we get to see the Victorian world—imbued with its sense that God created every creature—grappling with Darwin's new, godless world order.

Philosopher Herbert Spencer used the theory of evolution to champion ideals of "progressive advance," a first foray into social Darwinism. Henry David Thoreau "experienced the Origin of Species as a revelatory text." Karl Marx sent a copy of Das Kapital to Downe inscribed to "Mr. Charles Darwin on the part of his sincere admirer." Alfred, Lord Tennyson changed a line of the poem "In Memoriam" from "Since Adam left his garden yet" to the less biblical "Since our first sun arose and set."

When the battle dies down, we understand why Darwin seems happy enough to return to investigations of climbing vines and earthworms. But we also sense that Darwin remains alone with the lingering doubt that while many have finally come to accept his version of the origin of species over that of the Bible, the most basic principles of evolution as he saw it remain unappreciated even by his most ardent supporters. These tenets are, first, that natural selection doesn't occur for "the good" of the species but rather for the good of the individual. And second, that evolution has no direction, for the good or toward the best. These misconceptions persist today—from the purveyors of creationism and from advocates of the equally spurious theory of intelligent design.

The intensity of Browne's focus on Darwin and his coterie sometimes leaves the reader as fixed in time and place as the players about whom she writes. Although Darwin wasn't aware that Mendel had solved the problem of inherited characteristics in a paper published in 1866, the reader might have benefited from an account of that seminal discovery. And following the vivid portrayals of Darwin's family and members of his inner circle, an afterword that revealed the fate of these major players and of Darwin's work might have given the reader a better sense of closure. But Browne is true to her subject, to his time and his place. We're afforded the privilege of seeing the world through Darwin's eyes; when his eyes finally close, we awaken anew to our own.

October 2022 Science Movies

Techno Kingdom Fast-forward to a digital world gone wild

By Alan Burdick

NAQOYQATSI Miramax Films, October release

The most powerful sequence in GODFREY Reggio's new film about the perils of technology unfolds as a camera closes in on a giraffe galloping across the African veld. A running giraffe viewed from the rear is an improbable sight, all legs and neck, swayingly off-kilter; the only thing more absurd is the doggedness of the cameraman. The giraffe veers left, then right, then turns its head to see if it has lost us; it kicks up clods of dirt that fly straight into the camera, a rebuff to the viewer. The scene would be merely stirring or comic if not for an added element: With digital techniques, Reggio has swapped the color palette so that a green-spotted giraffe races against a sky as orange as industrial rust. The viewer careers through a landscape gone wrong, where technology advances with ruthless pleasure and nature runs for its life.

Photograph courtesy of Miramax Films

Naqoyqatsi, which draws its name from the Hopi term meaning "life as a battle," is the third in Reggio's trilogy of films about global change, following Koyaanisqatsi ("life out of balance") and Powaqqatsi ("life in transformation"). It is not a movie in the conventional sense: There is no plot, no narrator, no cast of characters. Rather, it's a spray of images, hundreds upon hundreds, assembled from a wide variety of existing footage (the giraffe, above right, might have run straight from a PBS nature show) and extensively manipulated—slowed down, sped up, colorized, bleached. It's a dizzying journey that evokes genetic enhancement, crowd violence, television advertising, urban decay, rural decay, and the overall digitalization of society, all without a single word spoken.

Picture The Matrix on acid. Some of the reworked footage—such as a recolored sequence of parachutists spilling from a cargo plane like seeds from a dandelion—is artfully sublime. And it's worth the price of admission simply to see snippets from The Human Figure in Motion, Eadweard Muybridge's classic (1901) early experiment in motion-picture photography. Spliced into Naqoyqatsi, the naked, jumping men of Muybridge's day become heralds of a new era: the dawn of modern science—man as studious observer, recorder, analyzer, manipulator—and of a new, aggressive desire to capture the world visually. Man starts out innocently studying his navel; next thing you know, he's chasing the giraffes with his camcorder.

The film's promoters have worried that Naqoyqatsi is "too cerebral." Certainly, it will make you think. Naqoyqatsi is nothing less than a meditation on the human condition. We humans are a bipedal paradox, simultaneously the products of nature and, with our big, fat brains, the sole outsider observers of it. "I may either be the driftwood in the stream or Indra in the sky looking down on it," Thoreau wrote. Estranged from nature, we exploit it outright, or approach it with such intense curiosity that we batter it in the process. In the old days, we'd go after the giraffes with clubs. Our video tools, Naqoyqatsi suggests, are hardly an improvement.

The argument is worth absorbing, but in Naqoyqatsi it lacks subtlety. The film's mood is uniformly morose, and the omnipresent score—by composer Philip Glass, performed by cellist Yo-Yo Ma—offers little relief. That's not to say an art film about technology should be peppy and bright. But it does call for a richer emotional palette. Humans observe, manipulate, use tools—that's what we do, that's how we're defined. If that trait alone constitutes violence against nature, how then should one proceed in this world? The filmmakers offer no insight and admit they are portraying the devil using the devil's own digital paintbrush. All the more reason, one might think, to add a few pale shades of sympathy.

October 2022 Science Best-sellers

1. Tuxedo Park: A Wall Street Tycoon and The Secret Palace of Science That Changed the Course of World War II By Jennet Conant, Simon & Schuster

2. A New Kind of Science By Stephen Wolfram, Wolfram Media

3. The Universe in a NutshellBy Stephen Hawking, Bantam

4. The Theory of Everything: The Origin and Fate of the Universe By By Stephen Hawking, New Millennium Press

5. I Have Landed: The End of a Beginning in Natural History By Stephen Jay Gould, Harmony

6. The Next Fifty Years: Science in the First Half of the Twenty-First Century Edited by John Brockman, Vintage

7. A Matter of Degrees: What Temperature Reveals about the Past and Future of our Species, Planet, and UniverseBy Gino Segre, Viking

8. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory By Stephen Jay Gould, Harvard University Press

9. Linked: The New Science of Networks By Albert-László Barabási, Perseus

10. How the Universe Got its Spots: Diary of a Finite Time in a Finite Space By Janna Levin, Princeton University Press

* Source: Barnes & Noble Booksellers

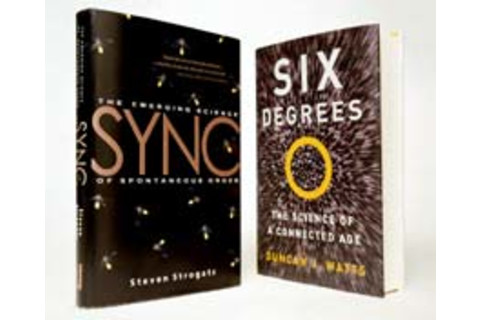

We also like...

Flash! The Hunt for the Biggest Explosions in the Universe Govert Schilling Cambridge University Press, $28

Gamma-ray bursts are fleeting and enigmatic. Schilling chronicles three decades of research that suggests these enormous blasts of energy from dying stars may be the precursors of black holes.

Travels in the Genetically Modified Zone Mark L. Winston Harvard University Press, $27.95

Winston, a biologist, argues that the various scientists, farmers, environmentalists, government officials, and consumers involved in the debate about the safety of genetically modified foods have gotten so caught up in defending their narrow convictions that they've hindered agricultural progress.

Elephantoms: Tracking the Elephant Lyall Watson W. W. Norton, $25.95

Drawing upon his personal observations during numerous expeditions to Africa, Watson portrays some of the surprising social aspects of elephant behavior—their extended childhood, their extraordinary capacity for memory, and the rituals they observe for their deceased relatives.

Unlocking the Sky: Glenn Hammond Curtiss and the Race to Invent the Airplane

Seth Shulman HarperCollins, $25.95

Shulman rescues Glenn Curtiss, a largely forgotten aviation pioneer whose inventions included wing flaps and retractable landing gear, from the shadow of the Wright brothers.

The Hungry Gene: The Science of Fat and the Future of Thin Ellen Ruppel Shell Atlantic Monthly Press, $25

Shell presents the current state of research into the genetics and biology of fat, the behavior of eating, and the politics of pharmaceutical companies that have invested billions of dollars in the treatment of obesity, which afflicts more than 19 million Americans. — Maia Weinstock

The Web site of the Atomic Museum includes a virtual tour and information about exhibits: www.atomicmuseum.com.

And to learn more about our nuclear heritage, see americanhistory.si.edu/subs/weapons/ballistic, energy.gov/aboutus/history/manhattan.hist. html and www.library.csi.cuny.edu/westweb/ pages/atomic.html.

Find Godfrey Reggio's biography and a host of information about the Qatsi film trilogy at www.koyaanisqatsi.org/films.