. . . and maybe even a drop to drink on some of them. The first planets discovered around other stars, though, don’t much resemble Earth.

Only a year ago astronomers were wondering when they would ever find planets around other stars. Now planets seem to be popping up everywhere. Last October came the discovery of one around the star 51 Pegasi, 57 light-years from Earth. And at a recent astronomy conference in San Antonio three more stars were reported to have planets. San Francisco State University astronomer Geoff Marcy was in on two of those finds. We are at the gateway of a new era of science, he told the throng and the television cameras in San Antonio. Marcy had reason to be excited: whereas 51 Peg’s planet probably has a climate like a blast furnace, both of Marcy’s planets are far enough from their stars that their surfaces could conceivably bear liquid water--the prerequisite, as far as we know, for life.

Nobody has seen any extrasolar oceans yet. Like the planet at 51 Peg, the new planets are lost in the glare of the stars they orbit. Marcy and Paul Butler of the University of California at Berkeley used a highly sensitive spectrometer to look for the gravitational influence a planet would have on a star. Just as stretching and compressing an accordion changes the distance between its pleats, the motion of a star pulled slightly toward and away from Earth by an orbiting planet can squeeze and stretch the light waves it emits.

For years now Marcy and Butler have been collecting such data, laboring without occasion for televised announcements. They had always expected the search to take a long time. For them to detect a planet, it would have to be at least the size of Jupiter, and they and other astronomers didn’t expect such a behemoth to be much closer to its star than Jupiter is to the sun. Jupiter takes nearly 12 years to orbit the sun, so to see a Jupiter pull a star back and forth you would have to watch for at least six years and probably even longer--or so it was widely assumed.

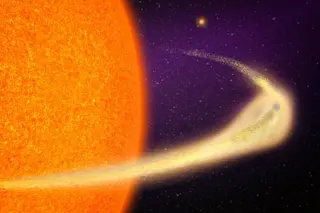

The planet at 51 Peg shattered that assumption. It is Jupiter- size but so close to 51 Peg that its orbit takes just four days. The wobble it produces in the star is huge; Marcy and Butler were able to confirm it by observing 51 Peg for a long weekend last fall. They knew then that it was time to start combing their own large data set in earnest.

By December they had their discoveries. At 47 Ursae Majoris, a star 42 light-years away in the Big Dipper, they found a planet three and a half times Jupiter’s size--yet orbiting its star at only twice Earth’s distance from the sun. The new planet at 70 Virginis, 60 light-years away in Virgo, could hold eight Jupiters. Yet it lies less than half the Earth- sun distance from its star.

Judging from their size, both planets may be gas giants like Jupiter, but from their orbits, both could support liquid water, like Earth. Marcy calls the planet at 70 Virginis Goldilocks; with an estimated temperature of 185° F, it is neither too cold nor too hot--and not just for water. This temperature is not too warm to prohibit the existence of complex molecules--perhaps organic molecules--on the surface or in the atmosphere of the planet, he says. Of course, he is speculating. It will be years before astronomers answer such questions.

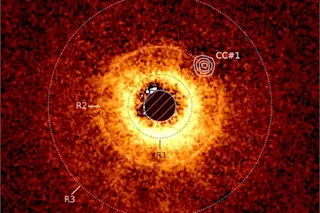

Meanwhile another giant may be lurking in a dusty disk surrounding the star Beta Pictoris, 50 light-years away. A Hubble telescope image made by Chris Burrows of the Space Telescope Science Institute and his colleagues shows that the inner disk is slightly tilted with respect to the outer disk--perhaps because the dust is being pulled by a planet. A planet of Jupiter’s mass and orbit, Burrows calculates, might do the trick.

If so, that would make Beta Pictoris the only new planetary system remotely like our own; the others all have giant planets in the wrong places. But astronomers still haven’t found enough specimens to know what a normal planetary system looks like. Right now this is stamp collecting, Butler says. We find a planet--great! But where does it fit in the greater scheme of things?

By the decade’s end he may know, when several teams using the world’s largest telescopes will have surveyed 1,000 stars. And in San Antonio, NASA administrator Daniel Goldin announced that the space agency was making the search for Earth-like planets (as opposed to Jupiter-like ones) a priority. In ten years or so, he says, we should have the technology to identify planets like our own and determine if they have life.