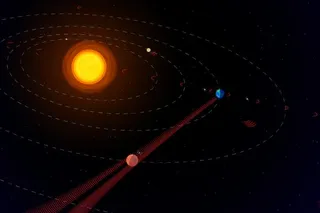

In 2012, scientists announced they’d found a planet, 55 Cancri e, that was made out of diamond. The idea was based on estimates of the planet’s size and density.

Soon after their work was published, however, other research suggested they’d been wrong.

Roger Clark, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, explains that to come to these kinds of conclusions, scientists work backward, starting with the size and mass of a planet. They use that information to estimate density, and then work to determine what kind of materials could produce that density. But, he says, “it’s not proof that those materials are there.”

While the entire planet of 55 Cancri e may not be made of diamond, there is good reason to believe that diamonds do exist outside of Earth, throughout the universe, along with other precious stones like opal, rubies, and sapphires.

“We can form all ...