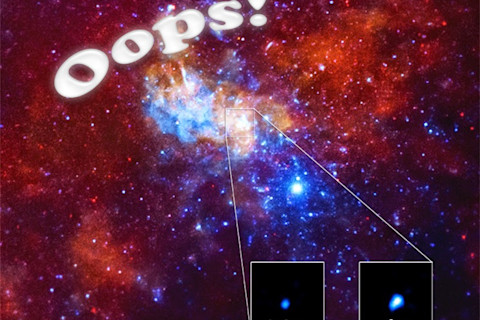

NASA/CXC/Amherst College/D.Haggard et al

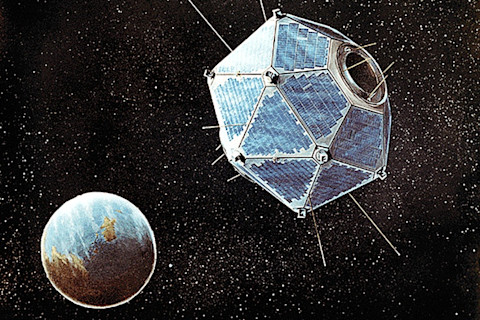

Courtesy of HEASARC, at NASA/GSFC

HEASARC, at NASA/GSFC

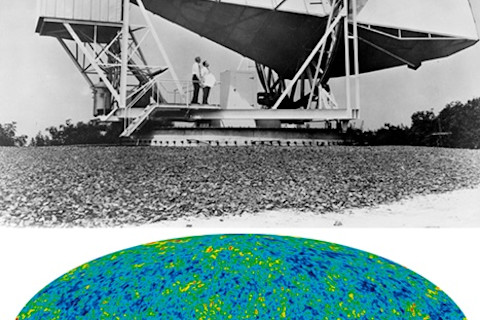

NASA / WMAP Science Team

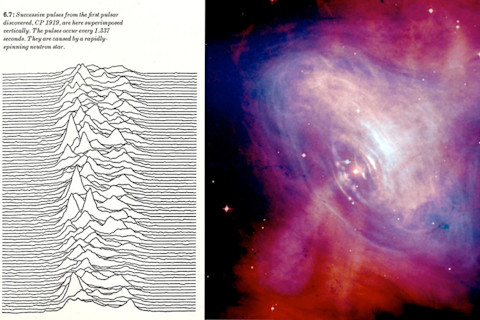

Right: Optical: NASA/HST/ASU/J. Hester et al. X-Ray: NASA/CXC/ASU/J. Hester et al.

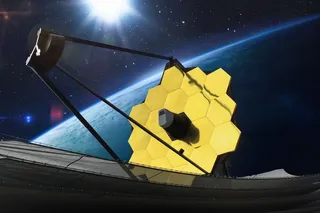

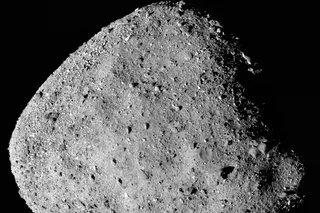

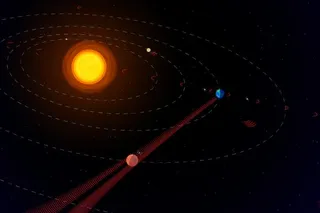

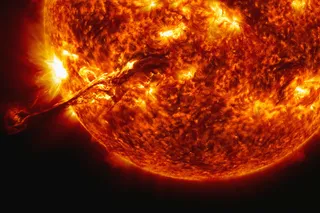

NASA

National Radio Astronomy Observatory

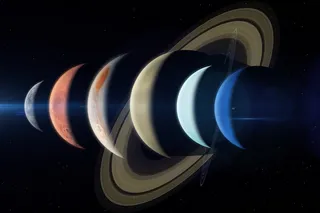

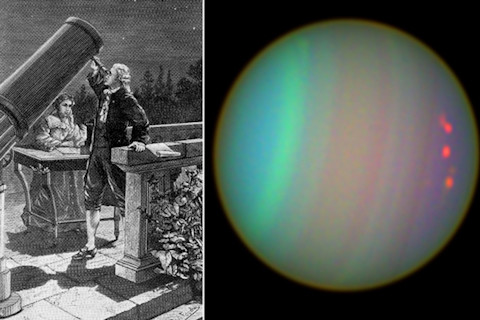

Right: NASA and Erich Karkoschka, University of Arizona

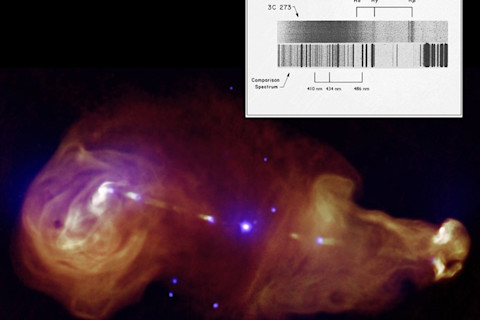

X-ray: NASA/CXC/Tokyo Institute of Technology/J.Kataoka et al, Radio: NRAO/VLA

NASA