Just as nature abhors a vacuum, humans can’t stand things not having names.

As soon as naturalists spy a never-before-seen creature or explorers stumble upon a new land, they set about christening their discoveries. This undeniable urge has led to some, shall we say, issues over the naming of exoplanets, the worlds beyond our solar system.

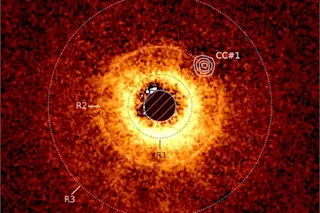

For the past 22 years, ever since finding the first exoplanets, researchers have generally preferred alphanumeric scientific designations blessed by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) — we’re talking exoplanetary handles like UScoCTIO 108b and TrES-3b. But now that scientists are finding thousands of new worlds, the populace is rising up to demand more prosaic names.

The ruckus over popular exoplanetary names finally reached a boiling point last year. The startup company Uwingu (meaning “sky” in Swahili), composed of several prominent astronomers — and IAU members — publicly thumbed its nose at the IAU. It ...