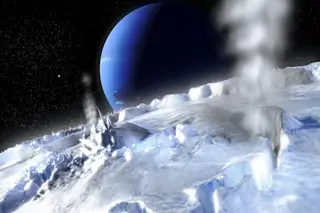

An eruption of Sakurajima volcano in Kagoshima, Japan.Getty Images We all love to get excited about new scientific discoveries. You see that in news articles all the time, that breathless tone that describes the latest studies as if we're reinvented the wheel. Suddenly everything is clear and we've solved all the problems! Or, oh no, we now know about new problems and we're all doomed! We're living in a world of shocking findings that will forever change the planet as we know it. Yet, really, it isn't actually that way. Day in, day out, scientists all over the globe are doing great work that isn't splashing across the headlines. Or, in particular, their work can't be easily sensationalized into something that gets easy clicks. Scientists aren't declaring predictions for an eruption or earthquakes in their papers. They aren't declaring long-standing science problems solved. They are presenting their data and hypotheses ...

How to Be a Savvy Science Reader

Learn about the Sakurajima volcano eruption predictions and the real science behind magma accumulation threats in Japan.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe