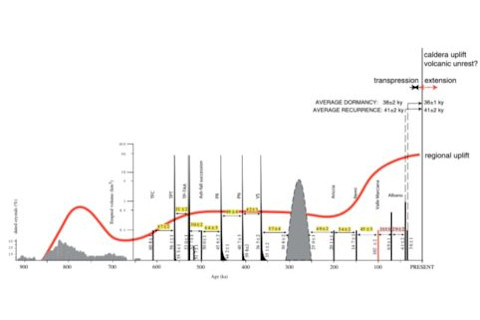

An aerial view of Castel Gandolfo, Lake Albano and the Alban Hills in Lazio, Italy.DeAgostini/Getty Images Italy has some of the most potentially hazardous volcanoes on Earth. The pair of Vesuvius and the Campi Flegrei around the Bay of Naples are a looming danger for over 3 million people when either of those volcanoes reawakens. Etna, although not as directly hazardous as Vesuvius, is one of the most active volcanoes on the planet, and its explosive eruptions can impact air travel. New research in Geophysical Research Letters by Fabrizio Marra and others is suggesting we add another to the list of potentially perilous Italian volcanoes: the Colli Albani Volcanic District on the outskirts of Rome. Now, the Colli Albani (also known as the Alban Hills) has already been identified as having a volcanic past. It consists of a large caldera (10 by 12 kilometers) that was likely created during the Colli Albani's most active period from 608,000 to 351,000 years ago. That's when it produced some massive explosive eruptions totaling over 280 cubic kilometers (67 cubic miles!) of volcanic debris. Since then, activity has calmed down, with a period from 309,000 to 241,000 years ago that was dominated by strombolian eruptions and lava flows (think Etna). The area's most recent activity has been mainly small explosive eruptions of less than 1 cubic kilometer each, forming small cones or maars (pits). This change in behavior is good news for Rome, because the Colli Albani appears to be more regular in the spacing of its eruptions than most volcanoes. In their new study, Marra and team identify dormancy and recurrence intervals for the Colli Albani that, since 608,000 years ago, have varied from 29,000±2,000 to 57,000±4,000 years, averaging 41,000±2,000 years between eruptions and 38,000±2,000 years between periods of renewed activity (see below). If you look at the last 100,000 years (Caution: small sample size!), Marra and others argue that the recurrence interval drops to ~31,000 years. Considering it has been 36,000 years since the last eruptions, they claim that the Colli Albani might be ready for new eruptions.

Figure from Marra and others (2016), showing eruptions at the Colli Albani over the past 900,000 years. The recurrence interval of eruptions is marked in yellow since ~600,000 years. The red line represents uplift in the area while the grey peaks represent the volume and duration of eruptions.Marra and others (2016), Geophysical Research Letters Why would the Colli Albani be such a well-behaved volcanic system when it comes to regularly-spaced eruptive activity? Marra and others suggest that the regional stress changes due the the tectonic setting (subduction and extension, a strange combination) of this part of Italy can cause the Colli Albani to become active again. As the stresses change, they can either seal pathways for magma to reach the surface (cause "dormancy") or open those pathways (extension), causing new magma to rise towards the surface, generating uplift and hydrothermal features. Based on observations of recent earthquakes and borehole data, it appears that the area has entered a period of extension in the last few hundred years. On their own, these ideas might be intriguing but not a cause for concern. However, studies of the land's surface around Rome by InSAR and geodetic surveys over the last ~50 years have shown 50 centimeters (~20 inches) of uplift in the parts of the Colli Albani that have seen previous eruptions. Since 1993, an area on the western side of the Colli Albani has been rising on average 2.6 mm (0.1 inches) per year. The region also saw small earthquake swarms in 1990-91. And regional geophysical studies suggest that somewhere beneath the Colli Albani—at depths between 5-10 kilometers (3.1-6.2 miles)—is a zone that could be partially molten magma. (To add to the fun, three years ago a new fumarole [vent for volcanic gases] opened near the Leonardo da Vinci International Airport, although its distance from the Colli Albani makes it a tenuous connection to this activity). So, we have a volcanic system that seems to regularly reactivate on timescales of ~31-36,000 years, and it's been about that amount of time since its last eruptions. Combine that with signs of volcanic unrest (albeit pretty mild signs), and you get an area that likely needs close attention, especially considering it is only 25 kilometers (16 miles) from central Rome. The problem here is that, although the past activity suggests this recurrence, it isn't like clockwork (or at least any good clock). We might be expecting a new eruption any time now, or be waiting for another 5,000 years. It is easy to be seduced by such statistical looks at volcanic activity, but the rubber hits the road when it comes to confidently believing in those statistical values (and I abhor saying any volcano is "overdue".) What works to Rome's advantage is the style of recent activity in the Colli Albani. Since 69,000 years ago, much of the activity has been small explosive eruptions. Those might impact people/property right around the Colli Albani, but likely won't be a direct hazard for Rome. There is the potential for ash disruptions from such eruptions and people living in the area directly surrounding the eruption might be displaced for years (or forever). However, unless something has changed at the Colli Albani, the vigor in the activity has been in decline over the last half a million years. The Colli Albani is an intriguing test case for potentially having a long lead time before new eruptions. Rome doesn't have to harbor the same apprehension that Naples must have for the Campi Flegrei* and Vesuvius. However, this would be an excellent time to start planning in case the Colli Albani does decide it is time to wake back up. *Interestingly, a recent presentation suggested that the current uplift at the Campi Flegrei is rooted in gas rather than magma moving.