An illustration of NASA's Stardust probe. | UC Berkeley/Andrew Westphal

Our solar system began as a swirling cloud of dust and gas, the remainders of exploded stars. In 1999, scientists launched a spacecraft called Stardust to take a better look.

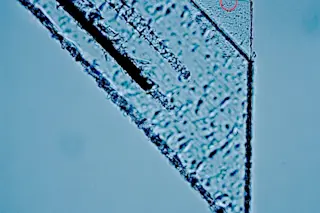

Three interstellar dust grains dug channels (the third is in the red circle above) within NASA’s Stardust probe. | NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

Stardust rocketed more than 3 billion miles around the solar system. Throughout the mission, particles of dust smacked into the spacecraft’s sample collectors, where they became lodged in an ultralightweight spongy material called aerogel. Seven years later, the probe returned to Earth, landing in Utah with its tiny precious cargo.

Last year, scientists announced that seven of those teensy dust particles — stuck in the Space Age gel — seem to come straight from the solar system’s original embryonic cloud, based on initial analysis. They are likely ...