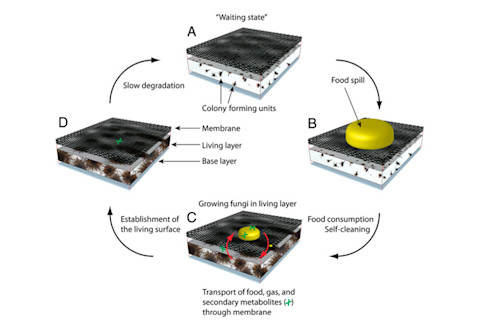

How a living material of cheese fungi sandwiched between plastic sheets works.

The crusty rind of cheeses like Camembert provide more than texture: they are miniature fortress walls, made of fungus, that protect the cheese's creamy insides from bacterial invasions. Now, taking inspiration from this delicious snack, chemical engineers at ETH Zurich in Switzerland have shown that such a fungus can be enclosed in porous plastic and will digest spills

, with implications for creating antibacterial surfaces from living material. The team sandwiched a layer of Penicillium roqueforti

---from, you guessed it, Roquefort cheese

---between a plastic base and a top sheet of plastic with nanoscale pores that allowed gas and liquids to move through, but did not allow the fungus to spread. Then, they mimicked a kitchen spill by pouring sugary broth on the surface and watched as, over the course of two weeks, the captive fungus gradually consumed the entire spill, leaving the surface clean. As shown in the figure above, the fungi can go dormant when there is no food around, so if one had a countertop of such a material, you wouldn't need to keep spilling sugar on it to keep the fungi happy. The researchers suggest that with different kinds of fungi, one could develop a surface that would degrade bacteria that ventured across it or a surface that performed some other service, with the added benefit that such a living surface could evolve to contain a population of fungi with skills appropriate to the task at hand. For instance, here's a thought experiment: let's say you live in a damp region and have problems with mold on your house's facade. If you paneled the exterior of your house with such a material, the fungi could eventually adapt to live on and efficiently degrade the most readily available food source: the mold.

Image courtesy of Gerber et al. and PNAS