The day João Magueijo began to doubt Albert Einstein started inauspiciously. It was a rainy winter morning in 1995 at Cambridge University, where Magueijo was a research fellow in theoretical physics. He was tramping across a sodden soccer field, suffering from a hangover and mumbling to himself, when out of the gray a heretical idea brought him to a full stop: What if Einstein was wrong? What if, rather than being forever constant, the speed of light could change? Magueijo stood there in the downpour. What would that mean?

Until this strange notion intruded, Magueijo had been mulling over the most fateful moment in the history of the cosmos, an inconceivably brief instant between 10^-37 and 10^-34 second after the Big Bang. During that tiny interlude, most theorists agree, the universe exploded a second time, doubling in size over and over until a cosmos far smaller than a single proton grew to the size of a grapefruit. It has been expanding ever since, albeit at a more leisurely pace. Inflation, as that primordial growth spurt is called, has dominated cosmological theory for the past 20 years because it explains why the universe looks the way it does today.

But Magueijo never liked inflation theory. The idea that the universe expanded from a subatomic mote in less than a billionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a second seemed unlikely at best to him, and there are obvious problems with the theory. It relies on a mysterious inflationary field and a weird antigravity particle called an inflaton, neither of which has ever been detected. Magueijo decided there must be a better explanation, and on that wet winter morning eight years ago, it came to him. Cosmologists wouldn't need to invoke inflation if they could bring themselves to give up one of their most sacrosanct laws: The speed of light is, was, and ever shall be 186,282 miles per second.

Magueijo now believes that for a few moments at the beginning of time, the universe's extreme heat made photons—particles of light—zip along much faster than 186,282 miles per second, at almost infinite velocities. Then, as the universe began to expand and cool, its physical properties abruptly changed, just as water suddenly transforms into ice at the freezing point. When the temperature dropped below a critical transition value, light "froze" at the lower speed we now observe.

"It's an act of brutality against the framework of physics," he admits. "You're conflicting with Einstein's theory of relativity—it's very line one. You have to be careful."

Magueijo's ideas have come under heavy fire from some physicists, but no one takes issue with his brilliance. Even before he developed an alternative speed-of-light theory, he was among England's most promising physicists, honored by a succession of prestigious scholarships. "João is quite courageous," says John Moffat, a theoretical physicist who recently retired from the University of Toronto. "He's pushing the envelope, saying, 'Let's see what we can get out of this.' He's not just following the standard route."

Ironically, the same could have been said of Alan Guth, who, as a young physicist at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, created the theory of inflation. Guth's ideas were decidedly out of the mainstream when he first formulated them in the late 1970s. Now there are tantalizing clues that Magueijo, too, may be onto something. Observations by an Australian astronomer suggest, indirectly at least, that the speed of light may indeed have changed over the past 12 billion years. If those results hold up, the implications are far richer than even Magueijo could have imagined on the soccer field that morning: Black holes may still be black, but they aren't holes; travel to the stars may not be an impossible dream. The theory even predicts how the universe might end—and how it may be reborn.

João Magueijo read his first copy of The Evolution of Physics, by Albert Einstein and Leopold Infeld, when he was 11. Seventeen years later, he set out to take that evolution one step further. | Mark Mattock

Magueijo is a handsome man of 35 with an easy smile, neatly trimmed black hair, and an athletic build honed by years of karate practice. He was born in Évora, Portugal, a small town southeast of Lisbon that dates to pre-Roman times. His father was a professor of classics, but Magueijo gravitated to science at an early age, mastering Einstein's theory of relativity when he was just 14. By the time he earned his Ph.D., his work in physics was so impressive that Cambridge awarded him a scholarship that had previously been given to Abdus Salam, a Nobel laureate, and the British physicist Paul Dirac, who helped build quantum theory.

Magueijo describes himself as an anarchist—he hates meetings and bureaucracy—yet he quickly adapted to the rigor and eccentricity that characterizes Cambridge. He remembers hearing that one student, citing an obscure, centuries-old university regulation, requested—and received—a beer while taking an examination. Still, there were limits.

"Along the corridors in the physics department I would tell everyone about my big idea," Magueijo says. "The reaction was so negative. People either laughed or looked at me like I was mad. Usually physicists have this natural curiosity. This didn't trigger natural curiosity. The only thing it triggered was laughter." When Magueijo began referring to his theory as VSL, short for varying speed of light, one physicist quipped that it really stood for "very silly."

The disdain threatened more than Magueijo's pride. His research position at Cambridge was near ending, and he needed to find a permanent academic post. Certain that no university would hire him if he openly pursued his theory, Magueijo concentrated instead on cosmic strings—extremely dense threads of matter and energy that may crisscross the universe. "I had to find a job," he says. "This was the main reason I left my theory on the side for a bit." At the time, many theorists thought cosmic strings might provide a noninflationary explanation for the development of the early universe. Magueijo's research seemed to show otherwise—while cosmic strings may exist, they can't replace inflation. "I wrote a paper that was the death blow to cosmic strings," he jokes. Nonetheless, he might have continued to work on them if not for an unexpected boon. In May 1996 he was awarded a prestigious Royal Society Fellowship. It fully supports a scientist for as long as a decade and allows him to work wherever—and on whatever—he wants. "It meant freedom," he says. "I wasn't going to be under the pressure of applying for a job for a long time, which means I didn't have to solve problems everyone wanted me to solve."

Magueijo soon decided that he'd had enough of cloistered Cambridge and moved to London to join the physics faculty at Imperial College. There he found a sympathetic colleague. "I needed a collaborator," Magueijo says. "These things aren't the product of a single brain. Theoretical physicists don't do experiments—we need someone to talk to, someone who will tell you: This is rubbish."

That collaborator was Andreas Albrecht, then the leading cosmologist at Imperial. Albrecht had made pivotal contributions to the theory of inflation, but he wasn't convinced that it held the final answer. "The way science really produces satisfactory results is when you have competing ideas playing out against each other," Albrecht says. "And then after a lot of work and tension and competition, one clearly wins out." No one had ever devised a significant alternative to inflation.

Albrecht and Magueijo worked in secret at first. If they were going to second-guess Einstein, they had to have something solid before going public. Their idea was revolutionary, but their methods were old school. They worked as Einstein did, on paper or blackboard, betting on the power of pure thought. "For more than a year and a half, I hardly did anything else," Magueijo says. "It was very depressing sometimes because to the outside world suddenly I had stopped being productive. Of course I hadn't, but I didn't tell anyone what I was doing."

The physicists assumed their theory affected only the very early universe. Once the speed of light froze at its current rate, the standard rules of physics would apply. But in that brief initial moment, a variable speed of light would solve two fundamental puzzles of cosmology.

The first is something physicists call the horizon problem: No matter which way astronomers look in the sky, the universe—at the very largest scales—looks the same. Clusters of galaxies spangle the cosmos in a remarkably uniform manner. How is it possible for opposite sides of the universe to be so similar? According to Einstein, the force of gravity, which determines the arrangement of everything in space, travels at the speed of light. How could such widely separated regions affect one another when the effects of gravity and other forces wouldn't have enough time to journey across the universe and back?

The theory of inflation solves the problem by suggesting that the regions of the universe once were in direct contact—back when the universe was only a few inches around, shortly after the Big Bang. Inflation simply blew them up, preserving the overall uniformity that astronomers still see.

What Magueijo realized was that variable light speed offered an easier solution. If light traveled much faster in the early universe, so would effects like gravity and temperature, which would have connected different regions of the cosmos without the need for inflation. "That was my first thought walking across that field," Magueijo says. "A varying speed of light could actually explain where the cosmic unity of the universe comes from."

The second challenge facing Magueijo and Albrecht's theory was more daunting. Cosmologists say that the shape of the universe is "flat," meaning that it's delicately poised between two extremes: eternal expansion and imminent implosion. If it had less matter—and therefore gravity—to brake its expansion, it would eventually swell to the point where we could no longer see any galaxies outside our own. If it had too much matter it would cave in on itself, crushing everything into an infinitely dense speck. Only a universe with just the right amount of matter and gravity would slow the expansion and reach a state of equilibrium.

In the four-dimensional mathematics that physicists use to describe the shape of the universe, each of these three possibilities corresponds to a unique geometry. A universe that collapses is the four-dimensional equivalent of a sphere; a runaway expansion produces a saddle-shaped universe; the third alternative is flat, like an infinite plane. "We basically have two catastrophes, a big crunch and an empty universe, looming over us," Magueijo says. "The universe really wants to fall into disaster if left on its own."

By vastly increasing the size of the cosmos just after the Big Bang, inflation skirts both catastrophes. It stretches out space-time in a single, magnificent burst—imagine a saddle or a sphere being pulled from all directions until it completely flattens out. But how could a varying speed of light possibly affect the flatness of the universe?

Despite months of trying, Magueijo and Albrecht couldn't find an answer. Everything they tried seemed to produce nonsensical, contradictory equations. "As soon as you allow for a varying speed of light inside any physical theory, it's such a mess that you can't imagine it," Magueijo says.

One obstacle was most worrisome. By letting the speed of light vary with time, the VSL theory broke another fundamental law: the conservation of energy. In conventional physics, the total amount of energy in the universe never changes. On the scale of electrons and neutrons, energy and particles of matter can spontaneously manifest out of sheer nothingness, but only for a few fleeting instants, and they promptly vanish again. That wasn't the case with Magueijo and Albrecht's theory. Energy could appear out of the vacuum and remain permanently in the universe. It could also drain away into the vacuum, leaving the cosmos forever.

This was bad news. Aside from varying the speed of light, Magueijo and Albrecht hoped to affect conventional physics as little as possible. The last thing they wanted to do was violate another basic law. They were at a dead end.

In April 1997, Magueijo left London for a three-week vacation in Goa, a former Portuguese colony on India's west coast. If we live in a flat universe, much of Goa seems to inhabit a cosmos of its own, a special space-time where the 1960s never ended. "It's a fun place, very psychedelic," Magueijo says. "The hippie scene is completely crazy. Some of them live in the tops of trees and go around completely naked."

It was just what Magueijo needed. After unwinding for a few days, he found himself scribbling on menus and jotting equations on napkins. "Most of my insights came from this period," he says. "It happens all the time. You try and try and it doesn't work. You stop thinking about it and it just comes." Back in London, Magueijo told Albrecht about his new inspiration: The solution to the flatness problem lay in the very violations of energy conservation that had seemed such a problem.

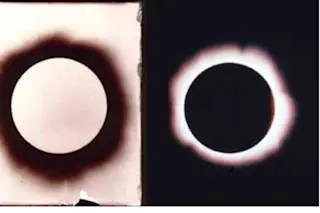

Magueijo's reasoning, ironically, harked back to Einstein. According to the general theory of relativity, space isn't a vast, empty theater; it's more like a hilly landscape, a cosmic terrain pocked by planets, stars, and galaxies. The greater a planet's mass or a galaxy's energy, the deeper the curvature in space-time. Before Einstein, celestial objects were thought to be tugged and towed by a mysterious gravitational force as they moved through space. After Einstein, they simply followed the invisible contours of space-time, dipping into shallow troughs around small planets or plunging into deep valleys around stars. Even light swerves when it passes a star: In 1919, during a total eclipse, astronomers observed light from a distant star bending as it shot by the darkened sun, confirming Einstein's theory.

If energy and matter distort space-time, then the spontaneous creation or destruction of energy and matter, in Magueijo's theory, would change the curvature of the universe accordingly. His cosmos is something like an enormous spring: When stretched or squashed, it naturally wants to resume its original shape. Because of the creation and destruction of energy through the varying speed of light, the universe rebounds spontaneously to a flat space-time.

According to Magueijo's equations, it works like this: If the nascent universe has too much matter, its overabundance turns into energy, which simply vanishes into the vacuum. Less matter means less curvature, so the universe flattens out. If the universe has too little matter at the beginning of time and is on the verge of being blown open, then it draws energy—and thus mass—from the vacuum. The increase in mass reins in the runaway cosmos, again flattening it out.

Magueijo hastens to note that energy conservation was violated only in the very early universe (and perhaps will be again in the distant future). At all other times, the usual laws of physics hold true. As for the vacuum itself—this strange region that spontaneously creates and destroys energy—Magueijo's description of it is less opportunistic than it seems. Many physicists assume that the vacuum is a vast reservoir of energy rather than the quintessence of nothingness. It may even be the source of so-called dark energy that seems to drive the expansion of the universe.

With their theory wrapped up, Magueijo and Albrecht were ready to go public. In 1997 they submitted a paper titled "Time Varying Speed of Light as a Solution to the Cosmological Problems" to the journal Physical Review D, the same journal in which Alan Guth had published his seminal paper on the theory of inflation in 1981. The editors, naturally skeptical of an article claiming to reinterpret Einstein, demanded several revisions before accepting it. "There was a one-year battle," Magueijo says. "Normally you get a paper through within a month. A year is very pathological."

When the paper was finally published in January 1999, Magueijo and Albrecht braced themselves for a critical onslaught. "I think it is a giant step backwards and will never catch on," says Neil Turok, a cosmologist at Cambridge University who also happens to be a good friend of Magueijo's. "You get more bang for the theoretical buck with inflation than you do with the varying speed of light."

Michael Turner, a cosmologist at the University of Chicago, feels that any alternative to inflation can be taken seriously only if it can account for all the cosmological mysteries that inflation explains. "I think we can now say that inflation has much of the truth about the early universe," he says. "Notice I said much, I didn't say all. It has passed a series of tests. The question is, how much of the truth? To get in the front door with another theory, you at least have to be consistent with inflation, and step one is being able to make predictions."

Magueijo says his theory can match inflation's accomplishments and insists inflation rests on shaky ground. "The inflationary field is a mysterious thing no one has ever seen," he says. "VSL is exactly the opposite. We don't introduce anything new in the universe in terms of ingredients. We just say the physics was different early on." Besides, he says, it's unfair to compare a two-decades-old theory like inflation with his newborn brainchild. "Things are normally not very pretty when they first come into the world. It's true of humans; it's true of everything. Then we start growing. A few hairs here and there; things start looking a bit better."

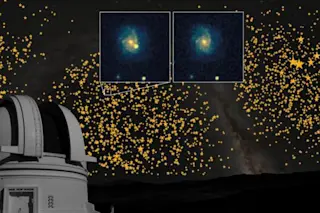

Magueijo's baby started looking much better two years ago. That was when a discovery by John Webb, an astronomer at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, made headlines around the world. "If the results are correct," Turner says, "this is certainly one of the most important discoveries in the last 100 years."

Webb used data collected by the world's most powerful telescope—the Keck, perched on the summit of Mauna Kea, 13,796 feet up on the Big Island of Hawaii. He looked at light from 68 quasars—extremely bright young galaxies—as much as 12 billion light-years from Earth. During the light's long journey to Earth, it passed through clouds of intergalactic gas. In doing so, the light's spectra changed, depending on the chemical elements in the clouds.

The details of such spectral shifts are expressed mathematically by the so-called fine-structure constant, which consists of four components, including the speed of light. The constant should remain the same no matter where or when it's measured—that's why it's called a constant. But Webb found otherwise. In the intergalactic clouds, the "constant" was smaller than the expected value by one part in 100,000. This means one or more elements of the fine-structure constant—possibly the speed of light—must have varied by the same amount. If light did travel that much faster 12 billion years ago, when it left the remotest quasars Webb studied, it would be consistent with Magueijo's theory. The difference may seem tiny, but it floored physicists around the world, including its discoverer. "I was absolutely stunned, yeah," Webb says. "I certainly didn't expect it."

Still, not many physicists are ready to give up on Einstein. "These are complicated systems they're looking at," Neil Turok says. "There are all sorts of things that can go wrong. Clouds of gas that could be turbulent; there could be lumps in the clouds, jets, and streams. Each of these things would affect what Webb measures. Personally, I think we'll need a much cleaner method if we're going to believe a result of such importance."

Webb sympathizes with the critics. "I often think that this is such an outrageous result that it must be wrong," he says. "But then again, when you look back at the history of the way things have happened in physics, even within the last 100 years, there have been equally—at least equally—outrageous results."

Right or wrong, Webb's results triggered a surge of interest in Magueijo's work. Where he once had just one collaborator, he now has several around the world. For the past two years, Magueijo has been working with Lee Smolin, a leading theoretical physicist at the Perimeter Institute near Toronto. Magueijo and Smolin are exploring whether the varying speed of light theory might help physicists achieve an elusive goal: the unification of the microscopic world of quantum mechanics with the cosmic realm described by general relativity. Magueijo suspects that physicists will never unify the two theories without breaking rules. He points to Dirac, his forerunner at Cambridge. "Dirac thought it was completely ridiculous to assume that the laws of nature have never changed," he says. "The universe might be trying to tell us something."

Sitting in his office at Imperial College one rainy October afternoon, Magueijo wonders about the end of the universe, as he once wondered about its beginning. Astronomers have recently discovered that the expansion rate of the universe seems to be accelerating, driven perhaps by the same vacuum energy that shaped the universe some 15 billion years ago. According to Magueijo's calculations, this surge in the expansion rate is but a prelude to another stupendous infusion of energy from the vacuum in the far distant future. When that happens, the universe will essentially undergo another Big Bang. This sequence of Big Bang, expansion, Big Bang, would never end. If the varying speed of light theory is right, the universe is eternal.

A phone call interrupts his musings. Magueijo talks excitedly for a few minutes, then hangs up. "That was John Barrow," he says. Barrow, a physicist at Cambridge, told him about a research team that just might be able to create an earthbound version of Webb's measurement of spectral shifts. Instead of looking for changes over billions of years, as Webb did, the researchers would set up a tabletop experiment that would run for two years. Since Webb's results suggest a decrease of only one part in 100,000 in the speed of light over 12 billion years, any change in two years would be even more minuscule—and extremely difficult to measure. But because the experiment would be done on Earth, the results would be much more convincing—and repeatable by other physicists.

"There you have it," Magueijo says. "A phone call can change everything. Only a few minutes ago I never thought an experiment on Earth would be possible. It's a surprising world." He shakes his head and remembers that rainy morning eight years ago. "Maybe if I hadn't had a hangover, I never would have thought of it."

Starships, Strings, and High-Speed Space Travel

Einstein's laws don't completely rule out the possibility of interstellar travel, but they do make it extremely unlikely. Any would-be starship captain faces two obstacles. First, nothing can travel faster than the speed of light. Since the closest star to Earth is about four light-years away, even a spaceship traveling at half the speed of light would need eight years for the voyage. (Such a starship would be about 18,000 times faster than a space shuttle in orbit.) Second, Einstein's theory of special relativity dictates that time itself would flow much more slowly on a rocket moving at near light speeds than it would on Earth. So even if we could build fast starships, would anyone want to travel in them?

"The problem with interstellar travel is not really that things are so far away—it's coming back and finding that what for you was one year was 1 million years on Earth. That is pretty depressing," says physicist João Magueijo.

Fortunately, Magueijo's varying speed of light theory could exploit a loophole in Einstein's unbreachable rules. Magueijo admits the idea is far-fetched—something he pursued for fun. But it is mathematically consistent within the framework of his theory. He calls it fast-track space travel. The tracks in this case are cosmic strings: concentrated strands of energy, thinner than an atom, left over from the Big Bang. No one has yet observed cosmic strings, but some theories predict that they should crisscross the cosmos. A three-foot-long piece of one cosmic string would weigh about the same as Earth.

According to Magueijo's calculations, the speed of light near a cosmic string would increase dramatically: A spaceship traveling on one of these fast tracks could go well above the standard speed of light—186,282 miles per second—while still traveling at a fraction of the accelerated light-speed limit around the cosmic string. The laws of special relativity would still hold—time would slow down for the travelers. But because they would be traveling at a fraction of the cosmic string's light-speed limit, the effect would be minimized; astronauts could travel to the stars and return to Earth to find that months, not centuries, had passed.

What if Black Holes aren't Really Holes after All?

In conventional physics, light simply falls into a black hole—just like anything else that wanders too near those chasms in space-time—and never comes out again. That doesn't happen in Magueijo's universe. According to his calculations, if the varying speed of light theory turns out to be right, light comes to a full stop at the very edge of the black hole; it freezes and never enters the hole. Moreover, since nothing can travel faster than the speed of light—even in Magueijo's theory—all other motion halts at the black hole's surface too. Nothing falls in. So black holes aren't really holes after all.

"A black hole is like an edge to space," Magueijo explains. "Nothing can come out, but nothing can go in either."

If an unlucky astronaut traveling along a cosmic string were to swerve near a black hole, the spaceship would seem to move more and more slowly. The black hole would remain forever in the distance, an unreachable obstacle.