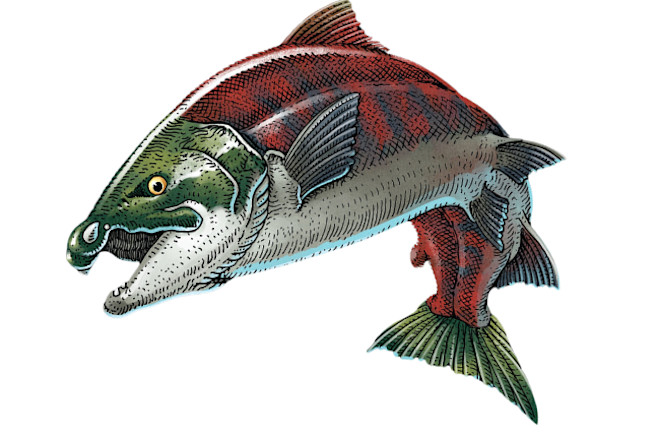

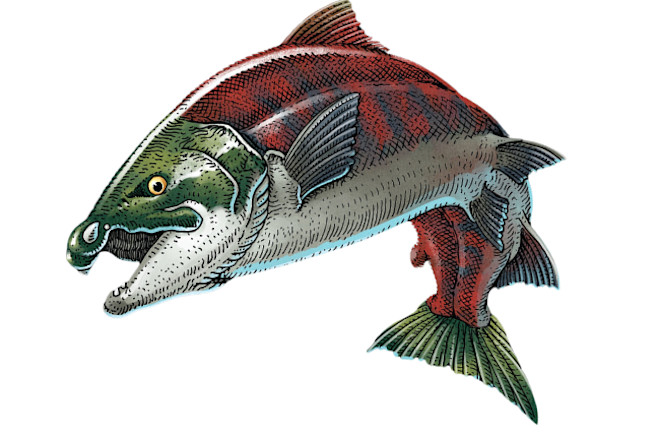

Artist’s rendering of complete female iconic fish with accurate spike-tooth configuration. (Credit: Ray Troll, Claeson et al., 2024, PLOS ONE)

A giant, tusked salmon was once thought to resemble a fish version of a saber-toothed tiger. But turns out, it looked more closely to an aquatic warthog.

A newly reported fossil find is now prompting paleontologists to rethink the nickname of the largest known salmon species — Oncorhynchus rastrosus, according to an article in PLOS ONE. The fish, which grew to nearly nine feet long, lived 3 million to 5 million years ago in the Pacific Northwest.

Oncorhynchus rastrosus. (a) CT model of holotype, skull in right lateral view with a stylized drawing of the originally proposed “sabertoothed” position of the isolated premaxilla; (b) anterior view of skull, prior to complete preparation and CT scan; (c) artist’s rendering skull of male iconic fish with accurate spike-tooth configuration; (d) artist’s rendering of complete female iconic fish with accurate spike-tooth configuration.

(Credit: Claeson et al., 2024, PLOS ONE)

A Saber-Toothed Salmon?