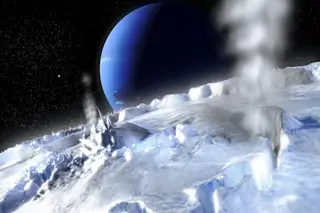

Getty Images Dangerous volcanoes are everywhere. But, how dangerous is dangerous or deadliest? Recently, I tried to tackle that notion and codify some ideas about what makes one volcano dangerous when it erupts, while another is merely spectacular. It turns out you can condense a lot of the hazard into a few main factors---and many of them depend on how many people make their homes near these volcanoes. To start building my list of most dangerous volcanoes, I mined the Smithsonian Institute/USGS Global Volcanism Program database. I found 63 volcanoes with over 10 million people living within 100 kilometers (62 miles)—and 14 of those have erupted in the last 200 years. Gede-Pangrango in Indonesia has over 40 million people living within 100 kilometers of the volcano. And 32 of the 63 volcanoes with 10 million people living within 100 kilometers are in Indonesia. If we expand this and think about ...

All the Ways To Know If That Volcano Might Kill You

Discover the dangerous volcanoes worldwide and how population density influences eruption risks and their devastating effects.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe