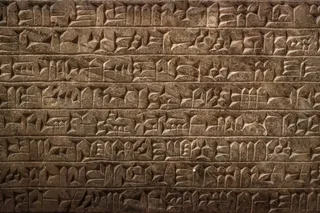

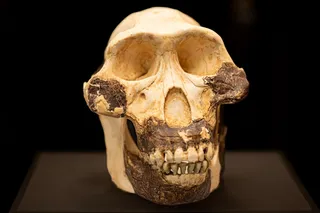

Since the invention of agriculture 11,000 years ago, human population has trended up—but the boom may be drawing to an end. Birthrates are falling around the world; by the end of the century the number of people on the planet may top out and, in an unprecedented reversal, start to decline. Good news, right? The answer is not so simple. Growing populations are associated with progress; shrinkage has often correlated with cultural decline. One stark example comes from Tasmania, an island off southeast Australia. Nearly the size of Ireland, it was colonized 34,000 years ago by people with sophisticated toolmaking skills who came across a land bridge from Australia. By the 18th century, Tasmanians used simple technology, hunting with rocks and crude clubs. In 2004 anthropologist Joseph Henrich used a mathematical model of cultural evolution to tackle this mystery [pdf]. He concluded that the island’s population, about 4,000 in the ...

100,000 Years of Dramatic Population Changes

An ever-rising population has driven cultural advancement for millennia. What will happen when global numbers drop for the first time in modern history? The past offers clues.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe