A colorful, sputtering Perseid meteor was photographed last night by Terry Allshouse near Eustis, Florida, and posted on the Realtime Meteor Gallery. All that from something about the size of a pea! The most consistently reliable meteor shower—the Perseids—peaks tonight. Under clear, dark, unobstructed skies you might see 60 to 100 meteors an hour. And this year, nature is cooperating: The moon is a thin crescent that does not rise until dawn, meaning that the astronomical sky will remain wonderfully dark all night through. (Clouds are another matter; getting away from buildings, trees, and city lights is all up to you.) For tips on how to watch the Perseids, read through this helpful viewer’s guide prepared by our friends at Astronomy magazine. That will tell you what you need to know about how to watch. It’s a lot harder to find good information about what you are seeing. That’s why I’m here. 1. The best way to watch is to slow down. OK, I lied just now: This first item is about both the how and the why of the Perseids. Contrary to the fakery you may have seen in movies (or in the real, beautiful, but somewhat misleading time-lapse photos you may have seen circulating online), the Perseids do not create a blizzard of streaks through the sky. Remember: 60 meteors an hour means an average of just one per minute, and that includes many faint ones. If you are in a suburban location with moderate light pollution, you are more likely to see one meteor every two or three minutes—sometimes in bunches, sometimes with long dry spells. The solution is to embrace the slowness. Find a comfortable spot where you can sit or lie down and look up. Enjoy the stillness. Visit with the stars. Take in as much of the sky as you can. When each meteor streaks by, pay attention. How long did it last? How bright was it? Did it have any color? Did it leave a trail? There is a lot to see—and a lot of pleasure in simply not doing—once you settle into that frame of mind. 2. Perseid meteors are fast, but not deadly. One of the reason the Perseids are so bright is that they strike at a very high velocity, hitting Earth’s atmosphere at about 35 miles per second (roughly 60 kilometers per second). This shower also produces an unusual number of super-bright meteors, called fireballs. That may sound scary, but in reality we are talking about tiny objects. The ones responsible for fireballs might weigh as much as a walnut; the vast majority of the things you see are pea-size or smaller. Most meteors disintegrate at a height of 50-60 miles (100 kilometers or so), leaving nothing but extremely fine dust that wafts to the surface. You don’t have to worry about getting hit by a Perseid meteor…at least, not here on Earth.

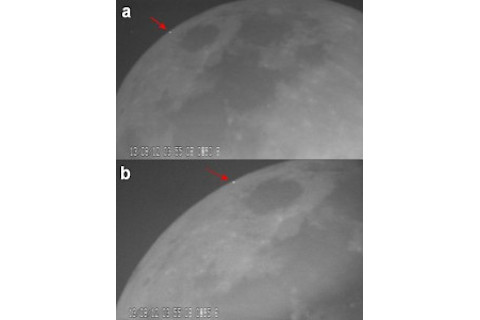

Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, parent of the Perseid meteor shower, photographed during its last bright appearance in 1992. (Credit: Gerald Rhemann) 3. The parent of the Perseids just might be a killer, though. The source of the Perseids is Comet Swift-Tuttle, which sheds bits of dust, rock, and ice each time it passes close to the sun, once every 133 years. That debris forms a cloud that slowly disperses through the comet’s orbit. Tonight’s Perseid shower represents the combined total of about 1,000 years worth of comet sheddings. They sound much prettier when you call them "meteors," don’t they? Since the debris trail of Comet Swift-Tuttle intersects with the Earth, it stands to reason that the comet itself could possibly collide with our planet as well. Possible, yes, but not very likely. The debris trail is about 10 million miles wide and 75 million miles long--huge. It’s a hard target to miss. By comparison, our planet is 7,913 miles wide, and the comet is just 16 miles across (big for a comet, small compared to the vastness of space). That said, in the year 4479 the comet will approach within 5 million miles of Earth. According to current calculations, there is a 0.0001% chance of impact. Prepare as you see fit. 4. We’ve observed Perseids striking the moon. Since it has no protective atmosphere, the moon does not ever experience meteor showers like Earth does. Instead, every incoming object makes it straight to the lunar surface. The rain of meteoroids (as meteors are called before they reach Earth’s atmosphere) creates miniature craters on the moon and steadily erodes the landscape there; it is one of the most important forms of “weathering” on the moon.

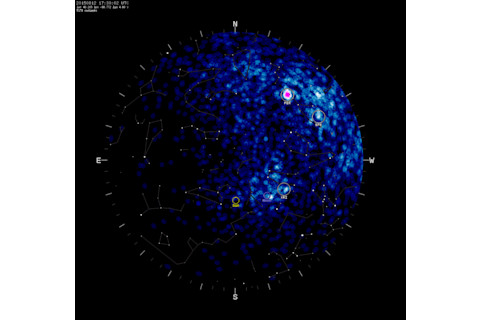

The white dot is a Perseid meteor colliding with the moon. How cool is that? (Credit: Madiedo et al, 2015) Instead of dumping all their energy in the atmosphere, Perseid meteoroids (and any other incoming objects) release their energy when they strike the lunar surface, yielding a small impact explosion. If the object is large enough, the flash is easily visible from Earth. Specialized cameras that watch the moon for impacts have recorded hundreds of such flashes, including ones specifically from the Perseids. Space probes have recorded meteor showers on other planets as well, including Mercury. 5. There is more than one Perseid meteor shower. People usually talk about the Perseid shower as one thing, but it is actually a whole family of meteor showers that are bundled together. Each time Comet Swift-Tuttle passes close to the sun it sheds material that gives rise to a new filament of debris. Subtle meteor surges and lulls occur as Earth moves through different parts of the stream, similar to what happens as you drive past rain clouds on the highway. The gradual spreading out of the filaments is why Earth plows through part of the Perseid meteor cloud up to a few days before and after the peak. If you can’t see the shower tonight, it’s still worth looking tomorrow or even the night after. 6. We've been doing this a long time. The Perseid shower has been observed at least since 36 AD, when a Chinese skywatcher reported that "more than 100 meteors flew thither in the morning.” When the shower actually first occurred is unknown. It was first identified as a recurring, annual event by Belgian astronomer Adolphe Quetelet in 1835. Just three years after the discovery of Comet Swift-Tuttle in 1862, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli realized that the Perseids have a nearly identical orbit and so much be related. Schiaparelli is better known for his detailed observations of Mars, which led him to note the existence of “canali” on the surface of the Red Planet. In Italian, canali means channels or depressions, and his description was largely correct. But canali got mistranslated into English as “canals,” wrongly implying that they were artificial constructions. Pretty soon you had American crank scientists like Percival Lowell talking about Martians and giant irrigation systems to save their dying society. Poor Schiaparelli. He was actually an extremely astute researcher. Let’s remember him for the Perseids instead. 7. You can see the Perseid meteors in radar. When a meteor races through Earth’s atmosphere, its kinetic energy is converted into heat, making it glow white hot. That is what you see as the streak of light. That heat also strips electrons off of air molecules, converting them into ionized (electrically charged) gas, known as a plasma. Plasma reflects radar, so it is possible to see meteor trails—even during the middle of the day—by bouncing radar waves off them. NASA does this routinely, and you can monitor the resulting radar meteor map online here.

Perseid meteor shower (pink spot at upper right) is visible here in broad daylight via the Canadian Meteor Orbit Radar. (Credit: CMOR/NASA) 8. You can hear the meteors...maybe. For centuries, people have claimed to hear sounds associated with meteor: hissing, sizzling, or pops. These reports were generally dismissed as figments of the imagination triggered by the feeling that a flash should be accompanied by noise. They seemed especially improbable since observers reported sound that was simultaneous with the flash; any sound waves coming from the meteor itself would take 5 to 10 minutes to arrive. Recently, some scientists have argued that the sounds may be genuine after all. One theory is that very low frequency radio waves created by the meteor could vibrate metal objects (or even hair strands) on the ground. Physicist Colin Keay at the University of Newastle in Australia claims to have been able to replicate the effect, and there are now many reputable reports of meteor sound. But there is still no consensus about the mechanism, nor even whether the phenomenon is real. There is one clear-cut way to hear a meteor: You can bounce radar off of it and convert the echo into an audible, and very spacey-sounding, bleep. 9. We’ve watched the Perseid meteors from space. In 2011, astronaut Ron Garan was keeping an eye out for the Perseid meteor shower, just like many other skywatchers, but with one big difference: He was looking down instead of up, since he was perched aboard the International Space Station. Turns out that the meteors are readily visible from above. Using his Nikon D3S, Garan got the beautiful shot shown below.

Perspective: A Perseid meteor flashes below the International Space Station on August 13, 2011. The green arc is the nighttime glow of Earth's upper atmosphere. (Credit: Ron Garan/NASA) 10. But you can also watch the Perseids from inside your house. If you have clear skies, I urge you to get out and take a look for yourself. Still, if you are rained out, or if your schedule simply does not allow it, you can still experience the cosmic connection. In addition to watching via radar (as explained in #7) you can monitor NASA’s All-Sky Fireball Network, or track the shower with expert commentary via NASA Ustream. And the Realtime Meteor Gallery lets you see the best photos from around the world. Better yet, you can share your own there, too, and become a part of the growing interplanetary community.

For space and astronomy news, follow me on Twitter: @coreyspowell