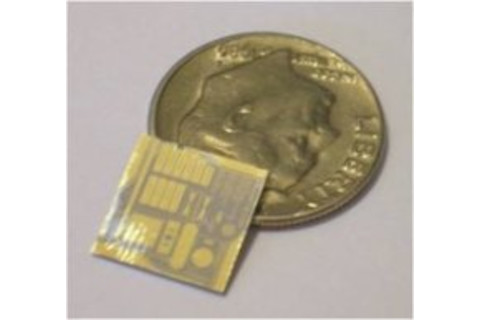

The chip at the core of the Sprite microsatellite is smaller than a dime.

What’s the News: Imagine a cloud of tiny satellites, each no larger than a postage stamp, sailing like dust on solar winds through a planet’s atmosphere and sending radio signals home, with no need for fuel. When a small patch of real estate opened up on an International Space Station experiment, researchers jumped at the chance to test the durability of such tiny “satellites on a chip,” which they hope to eventually deploy in atmospheres like Saturn’s, and three of the miniature objects are being delivered to the Space Station by Endeavor on its final flight (which was just scrubbed for today

). They will allow researchers to see how well such microsatellites hold up to radiation and other rigors of space. How the Heck:

The mini-satellites, developed by Cornell University and Sandia National Laboratories and called “Sprites,” are intended to take data about chemistry, radiation, and other properties—they could even be used to detect whether a planet’s atmosphere has any chemical signatures of possible life, such as nitrogen.

Instead of using fuel, the tiny printed squares of silicon would rely on physical phenomena already present in space to get around. The sun’s radiation pressure is one prospective source of propellant—essentially, light leaving the sun collides with small particles like dust and pushes them gently farther out into the solar system. The idea of such "solar sailing" has been around since the 1920s, and the first successful launch of a solar sail-propelled craft, IKAROS, was in 2010.

The satellites could also sail on electromagnetic effects like those that contribute to the formation of the rings of Saturn. Traditional spacecraft use fuel to surf a planet’s gravitational field to execute a flyby, while a charged Sprite chip would ride the planet’s electromagnetic field.

The three prototypes going into space on Endeavor each have a special radio signature that will let researchers tell them apart, which is key: when scientists release a cloud of the satellites into an atmosphere, each will be identifiable.

The Future Holds: While they are up there, the three Sprites on the International Space Station will be transmitting data back to Earth, and when they are returned to the researchers in several years, they will be examined for damage. Floating through space can be a dangerous business, and this experiment will help them deduce how Sprites would handle a real-life deployment. (via PhysOrg

)

Image credit: Cornell Space Systems Design Studio