Sometimes good things come in small packages. Researchers say they've developed a nanoparticle that can deliver cancer-fighting drugs to a tumor's blood vessels with laser-like precision, and that studies in mice show that this system could stop tumors from metastasizing, or spreading through the body.

Researchers say that packaging a toxic chemotherapy drug in nanoparticles for specific delivery to cancer cells, rather than a larger, wide-acting dose, could make for safer and more potent cancer treatments. "There are many drugs that companies have made that have fallen by the wayside or been shelved due to toxicity," says [study author] David Cheresh [New Scientist].

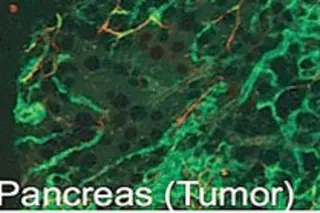

For the study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [subscription required], researchers examined mice with aggressive forms of pancreatic and kidney cancers. They used a nanoparticle that zeroed in on a tumor's blood vessels and delivered a payload of the chemotherapy drug doxorubicin, which can have serious side effects when given in traditional doses and delivered through the blood stream.

Using the nanoparticles, researchers found that a much smaller dose of the drug was effective, and it wasn't accompanied by "the collateral damage of weight loss or other outward signs of toxicity in the patient," said Prof Cheresh [Telegraph].

The mechanism's impact on metastatic tumors is of great interest to doctors, as these secondary tumors are harder to treat and are often the ultimate cause of a patient's death. A biotech company called Kereos hopes to commercialize similar nano-drugs, and plans to start clinical trials in humans within a few years. For insight into another nanotech approach to fighting cancer, check out this article from DISCOVER: "Killing Cancer With Red Hot Nanotubes." Image: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Researchers pointed out that the nanotech system didn't have a dramatic effect on the primary tumors, but that it did drastically shrink new metastatic tumors forming in the mice's spleens, livers and lungs; those shrunk 91 percent on average.

Cheresh said that newly forming tumors, still too small to be detected, depend on a fresh supply of blood. With doxorubicin rendering them unable to form blood vessels, the tumors didn't grow [Wired News].