Late last year, psychologist Gary Wells was watching an oral argument before the United States Supreme Court. He wasn’t enjoying it.

Wells, who has the countenance of a boxer and the mind of a Talmudic scholar, had come with a group of scientists affiliated with the American Psychological Association, along with lawyers from the Innocence Project, for the appeal of a convicted New Hampshire burglar. The case involved a middle-of-the-night car break-in. Police had apprehended Barion Perry in a parking lot carrying a couple of car radio speakers. One officer stayed with him while another went upstairs to question a woman who had reported a “tall black man” peering into cars. Although she had identified Perry only from her distant vantage on a third-floor balcony, her testimony was used successfully to convict him.

To Wells and his fellow scientists and lawyers, the case illustrated the weakness of many eyewitness convictions. The woman saw the suspect only briefly and in the custody of police; naturally she would assume he was a criminal. The psychologists agreed with Perry’s attorney that the witness’s memory was so unreliable that the judge should have held a pretrial hearing to determine whether it should be admissible at all. Now they wanted to go much further: They hoped that the Supreme Court justices would use the case to reexamine the whole legal question of eyewitness memory—a question the court hadn’t considered since 1977.

Wells, who is a distinguished professor of psychology at Iowa State University, is also an internationally ranked pool player and has developed the habit of looking at lots of situations from every possible angle. Before the hearing he did some research on patterns of Supreme Court discussions. He had learned that the sooner the justices interrupted an attorney, the more likely they were to rule against him. When Perry’s lawyer had spoken for barely 30 seconds before the justices began peppering him with questions, Wells knew it wasn’t going well.

Then the justices’ questions kept flying: What makes eyewitness testimony any less reliable than other forms of evidence? If a witness makes a mistake, can’t the lawyers reveal it during cross-examination? The courts already have rules for excluding witnesses who were coached or coerced by the police. Why is eyewitness testimony so unreliable that even without police misconduct it requires special jury instructions or a pretrial hearing? In January the Supreme Court ruled against Perry, 8 to 1.

It was a difficult case for Wells, and it won’t be the last. As one of the leading scientists in the esoteric field of eyewitness psychology, he has spent decades trying to overturn conventional wisdom and centuries of legal precedent.

Wells has a big job. eyewitness testimony has been a mainstay of justice since biblical times. Even today it holds almost magical power over judges and juries. As Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan wrote in 1981, “There is almost nothing more convincing than a live human being who takes the stand, points a finger at the defendant, and says, ‘That’s the one!’ ”

But according to hundreds of studies over the past 30 years, there is almost nothing less reliable than what an eyewitness thinks he saw. Memory is not videotape. We may believe that we remember things precisely, but most of our memories are a combination of what we think we observed and information we have been exposed to since then. The situation becomes worse at crime scenes, where variables such as stress and the presence of a weapon interfere with accuracy. If you regard memory as trace evidence—which most of the field’s psychologists do—it is the most delicate and easily contaminated kind. Yet police take less care in collecting and preserving memory than they do with, say, blood smears or partial fingerprints. And most courts pay scant attention to how memory-evidence was collected and retrieved.

Of the 297 cases that have been overturned by DNA evidence in the United States, more than 70 percent were based on eyewitness testimony. Those witnesses were not liars or jailhouse snitches but ordinary people utterly convinced that their memories were accurate. And this may be the tip of the iceberg. Tens of thousands of people are indicted every year because a witness has picked them out of a lineup. The implication: Across the legal system, a frightening number of people are being mistakenly arrested.

Wells’s early exposure to law enforcement often involved staring into the face of a furious policeman, because he grew up, as he gently puts it, “on the misbehavior end of the spectrum.” Raised in the rough-and-tumble town of Hutchinson, Kansas, Wells got into fights and hung around pool halls. By his early teens, he was making good money hustling adults. “Everyone there was drunk and dangerous—armed with a pool cue,” he recalls. “I learned to stay one stick-length away.” He hustled enough money for tuition at Kansas State, and by the time he was 21 he was married and had a kid. He developed a passion for social psychology, enough to earn him a cum laude degree and a graduate fellowship to Ohio State.

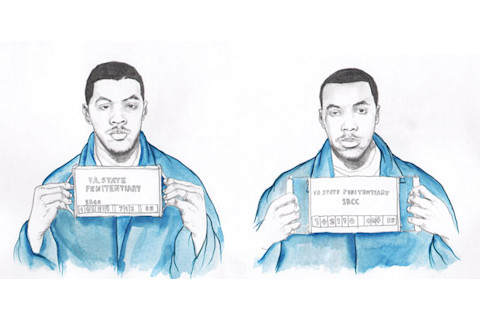

Thomas Haynesworth (left) was convicted in 1984 for a series of rapes after five women independently identified him as their attacker. He remained wrongfully imprisoned until 2011, when DNA evidence showed that the culprit was Leon Davis (right), a serial rapist who called himself the Black Ninja.

Wells traces his interest in eyewitness testimony to a chance encounter at grad school. An attorney from Cincinnati was walking the halls of the Ohio State psych department showing everyone he met a photographic lineup. “He said, ‘My client was misidentified in this lineup,’ ” Wells recalls. “‘You guys study memory. How could that happen?’”

Wells was intrigued. “I said, you’re right—we do study memory, but we don’t know anything about this.” Several months later he and some colleagues decided to enhance their knowledge by staging a simulated crime. They put out the word that they were recruiting students for a big study. When a student arrived to be interviewed, a member of Wells’s group was sitting in the waiting room. At one point, Wells’s confederate would put down a calculator and go to the men’s room—those were the days when calculators cost several hundred dollars—and another team member would come in and walk off with it. The idea was to see how many of the students could later pick the thief from a six-person photographic lineup. The result, after 65 trials: Despite good lighting and the proximity of the suspect, nearly 70 percent of the participants identified the wrong person.

Wells’s finding built on earlier studies that demonstrated how startlingly unreliable memory can be. In the early years of the 20th century, the renowned Harvard psychologist Hugo Münsterberg randomly staged crimes in his lecture hall and then asked students to remember the details. The responses were so varied and inaccurate that he realized that direct witnesses can have drastically different versions of the same event. That insight was reaffirmed by several psychologists who came of age during the 1960s and 1970s, most notably Robert Buckhout, a professor of psychology at Brooklyn College in New York. At one point, Buckhout persuaded a local television station to broadcast a simulated mugging and then ask viewers to pick the suspect from a lineup. Of the 2,145 viewers who called in, only 14.1 percent picked the correct man. Buckhout highlighted the experiment in an article he playfully titled “Nearly 2,000 Witnesses Can Be Wrong.”

More recently Elizabeth Loftus at the University of California, Irvine, demonstrated that memory is not only fallible, it is changeable. She showed that changes in the way people are questioned—even when the change amounts to a single word—can alter what they think they’ve seen. In a now-classic series of experiments, Loftus showed volunteers a video of a car crash and asked them to estimate the impact speed. The answers depended on whether she said one car “hit” or “smashed” the other. As her experiments grew in complexity, she found she could induce people to “remember” entire episodes from childhood (such as being lost in a shopping mall and rescued by a kindly old man in a flannel shirt) simply by dropping subtle verbal cues. Eventually she became embroiled in the notorious recovered memory controversy of the 1990s, in which adults thought they had discovered repressed memories of sexual abuse during childhood. Loftus testified that therapists sometimes created those memories by unwittingly dropping cues.

Studying those findings, Wells felt frustrated. Although eyewitnesses could be challenged at trial, no one was able to stop the errors up front. So he proposed a new way of structuring eyewitness research according to two practical categories of memory-based evidence. The first category included things beyond a detective’s control, including conditions at the crime scene, such as darkness, distance, or stress. Wells called these “estimator variables,” because their effects could be estimated only after the fact. A second category, labeled “system variables,” involved things a detective could control—for instance asking leading questions or deciding what kind of photos, lineups, or information witnesses saw.

Wells’s paper served as an organizing principle for the growing field of eyewitness psychology, and it has defined his career path ever since. Over the next several decades he ran more than 60 experiments involving more than 10,000 volunteers, all devoted to a single task: taking apart the controllable procedures and testing them one piece at a time.

When I visit Wells at Iowa State University, he is examining the effect of “confirmatory feedback,” the sense of certainty you get when you are told that you have answered a question correctly. Nicole, a student volunteer, watches a video of a man switching a bag with another passenger at an airline counter, presumably leaving behind drugs or a bomb. A student named Liz plays the detective. She shows Nicole a six-person photo array on the computer and asks if the suspect is among them. Nicole drums her fingers, hovers over several choices, then clicks on number four. “Good job,” says Liz reading from a script. “You got the right guy.” Nicole smiles briefly.

In the office next door another grad student, named Laura, follows up and asks Nicole how she feels about her decision. “Pretty certain, about 75 percent.”

“Did the detective say anything after you made the ID?”

“That I was right!” Nicole says, her fist raised triumphantly.

“And how did that make you feel?”

“Even more sure.”

What Nicole does not know was that she got the wrong guy. The real suspect’s photo had been left out of the lineup. Had this been the real world, Nicole would have fingered an innocent man; the jury would most likely have believed her because of her certainty.

That is what happened in 1985, when a young woman from Georgia named Jennifer Thompson testified with absolute certainty that a man named Ronald Cotton had raped her. Well-meaning police had encouraged her when she chose the suspect from a photo array and then again at a physical lineup. “By the time I went into court, everything added up for me,” she wrote in a memoir. “I was definitely confident that Ronald Cotton was the one.” Cotton spent 10 years in jail before DNA evidence proved another man’s guilt.

Wells has found that witnesses who make the wrong choice but get confirmatory feedback often feel more certain about their decision than witnesses who made the right choice but get none. A witness who wavers when making the original id but is praised by police will say at a trial two years later, “I’ll never forget that face as long as I live.” Such is the malleable nature of memory.

Other factors can distort a witness’s memory as well. Psychologist Roy Malpass at the University of Texas at El Paso found that the instructions given to witnesses can greatly affect the choices they make. Most people feel compelled to pick a photo from the lineup, even if they are not certain the guilty party is there. In one experiment, Malpass found that simply saying “the suspect may or may not be in this lineup” reduced wrong choices by 45 percent. Additional experiments have convinced psychologists that police should use double-blind methods when running lineups so as not to influence a witness’s choices: The officer who shows the witness a photo array should not be the one who is working on the case.

Wells’s most pivotal and controversial experiments have dealt with the structure of the lineup itself. In conducting simulated lineups over the years, he identified two pathways by which people make decisions. One involves absolute judgment, the kind of instant recognition in which someone might immediately cry out, “That’s him!” The other is a more deliberative process, in which the witness compares one face to another. “People would say things like, ‘I know it can’t be numbers one, two, four, five, or six, so it must be number three,’” Wells says. He calls that process “relative” judgment, since it involves deciding which face resembles the witness’s memory relative to the others.

In order to compare the two kinds of decision making, Wells and his colleague Rod Lindsay at Queen’s University in Ontario designed a new kind of lineup. Rather than showing six photographs together, they presented the photos one at a time. In other words, they replaced the traditional simultaneous photo array with a sequential one. In this way a witness would have to recognize the culprit instantly rather than pick him out from a group (thinking that the suspect had to be among them).

In the first of many trials, Wells and Lindsay showed a staged crime to 240 students and had half the students pick from simultaneous lineups and half from sequential ones. The sequential lineup reduced mistaken IDs by nearly half. Dozens of studies throughout the country have since confirmed that effect.

Wells says the distinction between “relative” and “absolute” judgment has applications beyond the lineup. Composite sketches, long a staple of police shows on TV, are notoriously inaccurate in real life. Unlike the way we recall other images—for instance, a two-story red-brick house with a screened-in porch and green awnings—humans are not programmed to construct faces by components. “The baby recognizes either ‘Mom’ or ‘not Mom,’ ” he says. “Not ‘Mom has that kind of eyebrows.’ ”

To demonstrate the point, Wells sits me down at an office computer and boots up one of the standard software programs that police departments use to create composite sketches. (Computers have almost entirely replaced human sketch artists.) “Imagine the face of someone you really know, like your father,” he says. “Now we’re going to build it.”

I summon a picture of my father in middle age: wavy hair, square jaw, hazel eyes. Wells clicks, and several hundred facial shapes appear on the screen. “Pick one,” he says. Instantly I see the difficulty of the task. Nothing in my mind’s eye corresponds to the featureless shapes on the screen.

“Just pick,” he says. “We can tweak the images as we go along.”

I pick one image that sort of looks like the right facial shape and ask Wells to alter it to my specifications. The next screen displays several dozen disembodied eyebrows. We repeat the process for many other features, including mouths, hairlines, eyes, noses—the program has 3,850 facial elements in all—until I give up in frustration.

“You start to realize you just don’t friggin’ know,” Wells says, laughing as he presses the print button. The sketch that emerges looks more like an ape-man than a person. “This is not how we store faces. We don’t store them in features. We store them intact.”

Wells says that anything that pushes us from absolute to relative judgment makes our testimony less reliable. To identify the tipping point where we go from recognizing a face to comparison-shopping for one, he has embarked on the biggest experiment of his career, testing nearly 1,600 people under 16 different conditions. In some cases, he will show videotaped crimes with blurred or darkened images; in others, lineups with blurred faces. The idea is to push the boundaries of instant recognition, identifying the point where a witness no longer recognizes the suspect but talks himself into committing to a near match.

Wells is convinced that by documenting that transition—by recording decision times and having test subjects vocalize their internal dialogue—he will be able to devise methods that can separate reliable from unreliable testimony.

These days, wells travels about 26 weeks a year as the unofficial head of a loosely affiliated cadre of academics, lawyers, and police officers proselytizing new procedures for judging eyewitness testimony. One goal is persuading detectives to see themselves as scientists. After all, Wells tells them, “You’ve got a researcher, hypothesis, design, procedure, subjects. You execute procedures, get results, and make interpretations.” He urges them to adopt rigorous protocols such as conducting lineups as double-blind studies: “We do this in medical research all the time.”

Wells’s efforts have begun to pay off. Thirteen states have mandated new, scientific procedures for lineups such as double-blind or sequential lineups, or have assigned commissions to create policies based on the new social science; five have signed on in the past year alone. And more than 40 percent of the nearly 18,000 police departments in the United States—from rural sheriff’s offices to metropolitan police—have adopted some or all of Wells’s suggestions for lineups, according to a survey by the Police Executive Research Forum. Attorney Barry Scheck of the Innocence Project contacted Wells more than 15 years ago and has been working with him to promote science in the legal system ever since. “His approach on system variables is in sync with my own,” Scheck says. “He has the tone and the approach that could change the field.”

Not everyone is a fan. Several prominent psychologists and attorneys say that laboratory experiments reflect neither the stress nor the confusion of real-world situations, and argue that Wells’s techniques have not been tested thoroughly enough to recommend as a legal policy. “I think he claims far more for sequential lineups than can be supported by the science,” says Roy Malpass, who has written several papers criticizing Wells’s conclusions. Malpass notes that in a 2006 field test of the lineup in several police stations, the state of Illinois actually found sequential lineups slightly less accurate than traditional photo arrays.

Wells and his colleagues from several other universities responded that the Illinois study was sloppily conducted. To prove their point, they collaborated on a field study of their own. The researchers selected four police departments—Austin, Tucson, San Diego, and Charlotte, North Carolina—and gave them laptop computers programmed to randomly administer simultaneous or sequential studies. Witnesses then conducted the lineups themselves, clicking through instructions and options on the computers. With no human directing the interaction, the data-gathering was consistent and double-blind. The results, released last fall, showed that sequential lineups produced the same rate of instantaneous identifications as traditional lineups. More important, the sequential lineups led to significantly fewer false identifications of people known to be innocent.

The implications of this research are enormous, and not only for the untold thousands of innocent people who have been convicted. As Wells puts it, every mistaken ID creates a “double injustice”: one for the convicted person but also another for the rest of us when the person who committed the crime remains free.