Invasive species extraordinaire and one helluva toxic toad. Photo by Chris Ison At the time, it seemed like the logical thing to do. Australian farmers were desperate. It was the 1930s, and beetles were tearing through their crops, especially sugar cane. Word spread of a toad that loved to gorge itself on the problem pests, which had been successfully brought to Hawaii to manage beetles in sugarcane fields. The Australians could have turned to pesticides, sure, but pesticides are expensive and often harmful to people and the environment. And if the toad could be introduced once, why not again? Why shouldn't they fix their bug problem once and for all with a harmless little amphibian? So in 1935, two suitcases of cane toads (Rhinella marina; formerly Bufo marinus) arrived in Australia. Those toads would go on to produce more than 1.5 billion descendants, contending for the title of worst invasive species in history. The cane toads didn't eat the beetles they were brought in to eradicate, but they do seem to eat everything else that fits in their fairly large mouths (the animals can get over 1 ft long and weigh several pounds!). Equally damaging is the fact that nothing on the continent can eat them — like other Bufoid toads, cane toads are armed with a potent poison that can kill unprepared predators hoping for a quick bite of cuisses de grenouille. The type of toxins they wield, called bufotoxins, strike at the heart. When a potential predator ingests the toad's defensive slurry, the toxins make their way through the blood to the cardiac muscle, where they bind to one of the key molecular components of contraction: a pump that moves sodium and potassium ions across cell membranes. Without this pump functioning, the heart cannot beat how it is supposed to, leading to life-threatening conditions and, often, death. Predatory animals in Australia didn't evolve with these toxic toads, so they have no natural defenses to the toxins, and the results have been devastating.

An Australian goanna, one of the many predatory species being wiped out by the invasive toads. Photo provided by Thomas Madsen "I started conducting my field work at Fogg Dam Conservation Reserve and the adjacent Adelaide River floodplain in 1989," explained Thomas Madsen, a scientist with the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Wollongong in Australia. But by 2000, the invasion front had made its way near to Madsen's study site. Knowing that native predators might be harmed by the new toxic prey item, Madsen and his wife, Beata Ujvari, started counting and tracking goannas (a large native Australian reptile) to get estimates of the local population before the cane toads arrived. "In October 2005, we found the first cane toad in our study area," Madsen said. "By 2009 the goannas were virtually extinct from our study site."

A dead goanna next to its killer: a cane toad it tried to consume. Photo provided by Thomas Madsen But while Australian predators are falling victim to the toads' toxins, their relatives in Asia and Africa are able to eat cane toads and their poisonous relatives with ease. In fact, the first goannas to arrive in Australia likely were resistant to bufotoxins, too, like their cousins. So Madsen and Ujvari wanted to know what had happened in the past 15-25 million years that made the lizards so vulnerable. To find out, the pair teamed up with Nick Casewell from the Alistair Reid Venom Research Unit at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. Together, they looked at the sodium-potassium pump genes of reptiles with and without bufotoxin resistance. "We found that, compared to Afro-Asian goannas, just the change of two amino acids had made the Australian highly susceptible to toad toxins," said Madsen. The researchers discovered that resistance had evolved on at least four separate occasions, always involving the same two changes. But, they also found that as soon as members of a resistant lineage stopped eating toads — like when the goannas arrived in the originally toad-free Australia — the genes reverted back, suggesting resistance to toxins was costly. "So now we knew why the Aussie goannas died when trying feed on the introduced cane toads... the Australian goannas had lost their resistance to toad toxin," Madsen said.

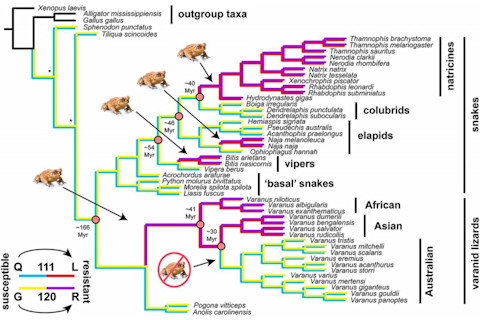

The evolution of resistance to bufotoxins occurred four different times! Figure 1 from Ujvari et al. 2015 While the reptilian results were exciting, Casewell wondered how other animals evolved resistance to bufotoxins. So he widened the search, looking at genes from insects to amphibians and even mammals. "The most surprising thing was the number of different types of animal that have evolved resistance in an extremely similar way," said Casewell. "In all of those that we were able to get data for, we found very similar resistant changes." Evolution has repeated itself over and over and over. "Its been previously described that few mutations can result in resistance to toxins," explained Casewell, "but our results here suggest that, in this system, there are limited options available for evolution and therefore when animals encounter similar strong selective pressures, resistance is funneled down repeatable pathways."

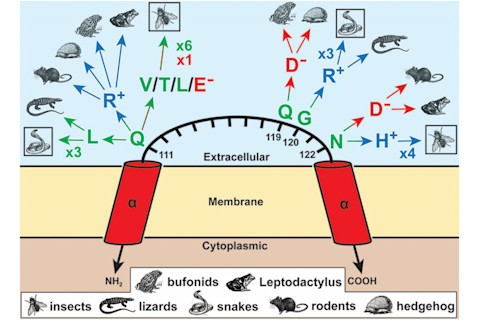

Same changes to confer resistence across many different species. Figure 2 from Ujvari et al. 2015 If evolution can be repeated, then it begs the question: can the Australian goannas regain their resistance in time to survive the cane toad invasion? "That's very difficult to predict," Caswell said. So far, it's not looking promising: Madsen and Ujvari have looked at the genes of lots of Australian reptiles, and none them have had one of the resistant mutations, let alone both. Citation: Ujvari, Beata, et al. "Widespread convergence in toxin resistance by predictable molecular evolution." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2015): 201511706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511706112 For more information on how this kind of evolution occurs, check out this awesome video from Stated Clearly: https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=2&v=DlhpvcgK_28