Contemplating world hunger from the vantage point of a well-laden breakfast table is certainly comfortable, if odd. One morning last January, executives of Iowa-based Pioneer Hi-Bred International, the world’s largest developer, producer, and marketer of genetically improved seed, gathered at the Friend of a Farmer café in downtown Manhattan for a discussion about global food security. Amid the restaurant’s rustic decor—dried hydrangeas in earthenware pots, autumn gourds tumbling from rush baskets, exposed brickwork—the three officials and a group of journalists sat dining on maple syrup–soaked buttermilk pancakes, muffins, corn bread, omelettes, and apple butter as Pioneer’s chairman and ceo, Chuck Johnson, outlined his vision of the future. The business we’re in is ensuring that the world has the capacity to have the food it needs to survive, he explained. That future capacity, he is convinced, can come only from the crops that companies such as Pioneer are producing: high-yield, insect-resistant ...

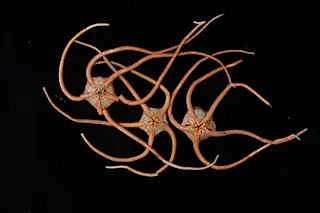

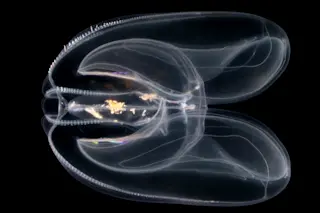

The Great Gene Escape

The seed companies say the plants they've created are safe. But who's to know what will come from a romp in the field with an untamed weed?

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe