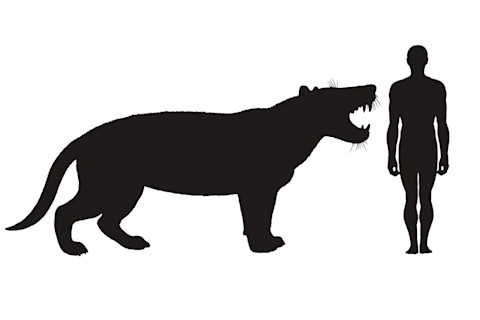

Simbakubwa kutokaafrika, was the lion-like king of Kenya 22 million years ago. The enormous carnivore, not actually a feline, is known from recently rediscovered partial fossils, including most of its jaw and pieces of skull, that had been languishing in a museum drawer. (Credit: Mauricio Anton) Take a polar bear. Take a lion. Mash them together and chuck them in a time machine, sending them back 22 million years to what's now Kenya and you've got the massive carnivore Simbakubwa kutokaafrika. The enormous bitey mammal was identified only after researchers rediscovered partial fossils of it, forgotten in the backroom of a museum. To be clear, Simbakubwa is neither a bear nor a member of the extended feline family, even though its name is Swahili for "big lion." Instead, the massive Miocene mammal was a hyaenodont, a now-extinct lineage of carnivores. Hyaenodonts emerged in the wake of the mass extinction that offed non-avian dinosaurs some 66 million years ago. (Hyaenodonts are not, by the way, related to modern hyenas, but they do have similar dentition.) During the Miocene (starting 23 million years ago), they spread across much of the world and some members super-sized. The hyainailourine hyaenodonts, in particular, are some of the largest terrestrial carnivorous mammals known to science. Paleontologists have placed Simbakubwa among the hyainailourine hyaenodonts, also called the hyainailourines. The massive animal is the oldest of these gigantic hypercarnivores from the region. They estimate that it may have been larger than a polar bear and weighed more than 3,000 pounds — that's much bigger than the modern lions it resembles.

A Simbakubwa silhouette contemplates the deliciousness of a modern human silhouette. (Credit: Mauricio Anton) The partial specimen — most of the jaw, some of the skull, additional teeth and a few other bones — appears to be that of a young adult, suggesting the animals could have reached even larger proportions. Hypercarnivores typically wear down their teeth as they age (crunching and shearing bones will do that), but because the animal died early in adulthood, its teeth are in great shape. Having relatively unscathed chompers to study means that researchers can use them to identify often subtle dentition differences among hyainailourines. This could help clarify their family tree, known mostly from fossil fragments and worn teeth. Lying In Wait Although not formally described until now, the Simbakubwa fossils were not a recent find. They were unearthed during a dig at Meswa Bridge, in southwestern Kenya, some 40 years ago. The focus of the excavation at that time was on finding Miocene primates, so Simbakubwa's remains were collected but then set aside without formal classification. (It's a great example of dark data: valuable scientific finds already in museums but not yet studied.) Paleontologists exploring the backroom collections at the National Museum in Nairobi found the undescribed fossils and recognized their importance. Yes, Simbakubwa was big, but size isn't the only thing that matters about this specimen. Finding a gigantic hyainailourine specifically in eastern Africa and during the very start of the Miocene tells paleontologists that the animals got larger earlier than thought. And the time when Simbakubwa lived was kind of crazy. Thanks to plate tectonics, Africa and Eurasia, once separate, were coming together, and animals from both sides crossed over landbridges into new territory, encountering alien species they had not evolved alongside. It's likely that some ecological niches got crowded. The very existence of Simbakubwa at this time and place helps scientists flesh out an early Miocene landscape that must have been rich in megaherbivores, similar to modern elephants and rhinos, to sustain the massive hypercarnivore. The study appears today in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

The skull of a modern lion (top) could have almost fit inside the enormous jaws of Simbakubwa, known from a partial fossil (bottom). (Credit: M. Borths)