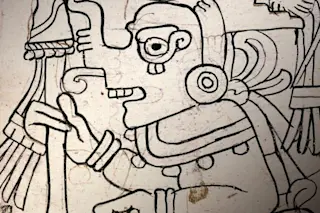

A detail of an image from page 4 of the Grolier Codex with red underpainting visible. (Credit: Justin Kerr) The Grolier Codex, a much-disputed Maya manuscript, is indeed the real deal, which makes it the oldest book discovered in the Americas. A team led by a researcher from Brown University performed a comprehensive analysis of the Grolier Codex, a collection of 11 sheets of bark paper discovered in 1965 in a cave in Chiapas, Mexico. They say that a number of factors point to the pages being authentic, putting to rest a debate that has gone on for over four decades.

Shady Past

Much of the debate centers on the initial discovery of the Codex, which was by looters, not archaeologists, and the checkered path it has taken since. The two men who discovered the Codex sold it to a Mexican antiquities aficionado named Josué Sáenz, who would eventually display it at the Grolier Club in New York in 1971, where it got its name. From there, the Codex disappeared, only to pop back up in 1977 after Mexican customs officials launched an investigation to find out why it had ever left the country in the first place. It sat for years in the basement of the Mexican National Museum of Anthropology.

Proving Its Authenticity

A 2007 analysis of the Grolier Codex couldn't verify its authenticity. In that study, the researchers affirmed that the paper it was written on was genuine, but raised concerns that modern-day forgers might have made the the drawings. Suspicious cuts on the outside of the pages and the absence of certain themes common in Maya iconography further suggested the Codex was a sham. After using radiocarbon dating and exhaustively analyzing the Grolier Codex's content, Brown researchers concluded that the manuscript is real, according to a press release. The deities depicted within the Codex weren't known when the manuscript first came to light, and are drawn too similarly to other representations to be coincidence. In addition, the composition of one of the pigments used, Maya blue, was not known at the time either, making forgery impossible. The Grolier Codex's radiocarbon-dated origin of 1230 AD, and the meticulously accurate depictions of Maya weapons all point to its authenticity as well. The researchers published their work in the journal Maya Archaeology.

Inside the Codex

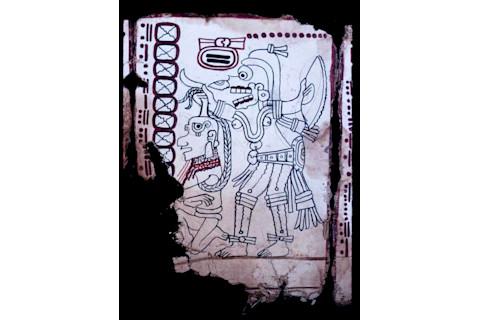

The Codex itself is composed of 11 figures, one to each page. Each figure faces left and is armed with a weapon; many grasp a chain tied to the neck of a prisoner. The Codex was likely used to track the movements of Venus in the sky, as the Maya based their calendar off the planet's movements. A series of markings down the left side of the page and numbers on the top tracked Venus' movements in the sky and marked its progress through various positions, each meant to foreshadow certain events. Venus was a harbinger of unfortunate events for the Maya, hence the foreboding demeanor of the drawings. In all, the calendar contained within spans 104 years, or 13 synodic cycles of Venus — the time it takes to come back to the same position in the night sky. The Grolier Codex breaks down each cycle into various phases, each associated with different events, and provided a means of organizing and predicting their cycle of rituals. The pages are in poor condition — only the top two-thirds or so remains of each, and the bottoms are water damaged. They are torn loose from the binding that once held them, and nine of the original 20 pages have gone missing.

The sixth page of the Grolier Codex. (Credit: US-PD/Wikimedia COmmons)

An Old Tome

This latest study makes the Grolier Codex the oldest ever discovered in the Americas, but it has aged company. Three additional Maya codices likely brought back by the conquistadors are currently housed in various museums in Europe: the Dresden, Paris and Madrid Codices, each named after the city where it resides. They contain depictions of rituals, horoscopes and prophecies, most tied to astronomical observations in the same way as the Grolier Codex. The European codices are much larger and more detailed than the Grolier Codex, and obviously better made, which was a key argument against the authenticity of the Grolier. However, the researchers are certain of the veracity of their findings, saying that they have addressed nearly every argument against the Codex's veracity. "A reasoned weighing of evidence leaves only one possible conclusion: four intact Maya codices survive from the Pre-Columbian period, and one of them is the Grolier," they write.