The earliest scorpion in the fossil record, Parioscorpio venator, also may have been the first to experiment with terrestrial living, according to new research in Scientific Reports. Preserved specimens include parts of the digestive, circulatory and respiratory systems, giving researchers clues about how the species lived.

Paleontologists believe that scorpions were among the first animals to leave marine environments and set all eight legs on dry land. The timing and details of that epic shift in lifestyle have been uncertain, however, because fossil evidence of the earliest scorpions is sparse.

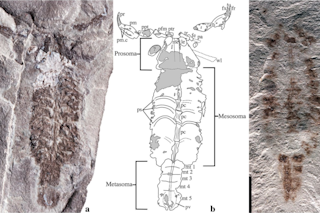

Parioscorpio fills in some of those details. The research team obtained two specimens from shallow marine sediment uncovered at a quarry in southeast Wisconsin. The layer preserving the pair dates to 437 million years ago, during the early Silurian. The newly described species is about two million years older than the previous titleholder of Earliest Scorpion.

One of the specimens preserves an incomplete telson, the final portion of its "tail." In living species, the telson includes a venomous stinger. Although Parioscorpio's telson appears to contain an enlarged area interpreted by the authors as a "poison vesicle," no stinger was present.

Internal Anatomy Clues

According to the authors, both fossils included some elements of internal anatomy that appear "essentially indistinguishable from those of present-day scorpions." One had what they interpreted as a gut tract. The other, more complete specimen retained a structure similar to a living scorpion's pericardium, which surrounds the heart.

The more complete fossil also preserved what might be mistaken for ribs by a casual observer (of course, as invertebrates, scorpions do not have ribs). The strut-like elements are actually cavities, or sinuses. In living scorpions and some other arachnids, these pulmo-pericardial sinuses connect the circulatory system to the animal's book lungs, a pair of respiratory organs that consist of thin, alternating layers of tissue and air pockets.

Alas, neither specimen of Parioscorpio preserved the book lungs themselves, which would have given researchers greater insight into whether the animals lived on land.

However, after comparing the fossils to both living scorpions and horseshoe crabs, which leave the sea to spawn, the authors believe that, even if not fully terrestrial, Parioscorpio would have been able to spend extended periods of time on land.