(Credit: imit Virdi/Shutterstock) When a chimpanzee sees a leopard, its reaction is appropriately intense and immediate: run away. Millions of years of evolution have embedded a natural fear of predators in our closest evolutionary ancestors' minds. However, a parasite found in cat feces, Toxoplasma gondii, may cause them to act irrationally bold when faced with real danger. Researchers in France and Germany examined the way chimpanzees infected with the T. gondii parasite reacted to leopard urine, and found an intriguing correlation: Those with the parasite displayed a marked lack of fear when confronted with signs of their most dangerous predator, compared with chimps free of T. gondii, who appropriately kept their distance. A link between infection and predation suggests that a similar process took place in prehistoric humans, who also counted big cats among their enemies.

Parasite Hitches A Ride

The parasite's life cycle begins when a feline eats an animal infected with T. gondii. Once consumed, the single-celled organism lives out the majority of its life in the feline digestive system, which is the only place it is able to reproduce. The parasite produces offspring, called oocytes, which eventually escape the cat via its feces. Smaller animals, in turn, ingest the baby parasites and are preyed upon by cats, starting the cycle anew. To boost its odds of reproductive success, the parasite, research has shown, infiltrates the brain of its host to influence behavior. Decades ago, researchers demonstrated T. gondii's hypnotic power in rat and mouse studies. Parasite-free rats turned tail at the first whiff of cat urine. But rats infected with T. gondii possessed a surprising level of bravado in the presence of cat urine — it didn't trigger a flight response. In some cases, rats even displayed sexual attraction to their age-old enemies, leaping into the clutches of a hungry cat.

In Chimpanzees

Some 30 percent of chimpanzee deaths are attributed to leopards, making them prime suspects for parasitic mind control. Researchers in the most recent study exposed 33 (nine infected and 24 non-infected) chimpanzees to leopard urine at the Centre International de Recherches Médicales de Franceville in Gabon, and found that infected subjects seemed unfazed by the warning signs of a deadly predator. Human, lion and tiger urine were used as controls, as none of them prey on chimpanzees. Infected chimps seemed to spend more time investigating leopard urine than the control samples.

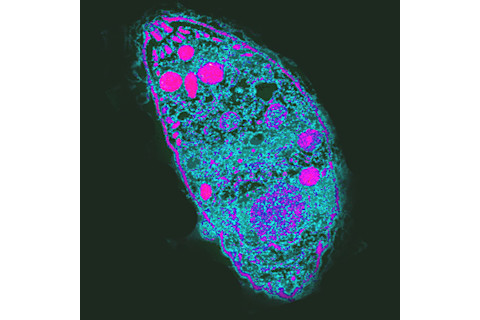

An image of Toxoplasma gondii. (Credit: AJ Cann/Flickr) This was in stark contrast to the healthy chimpanzees, who stayed away from the leopard urine samples as soon as they were noticed. Ignoring clear warning signs that a predator is near could increase the odds that infected chimpanzees are eaten, conveniently passing along the T. gondii oocytes and allowing them to reproduce. Researchers published their findings last week in the journal Current Biology.

In Our Heads

The chimpanzee study follows on the heels of recent research shedding light onto the sneaky ways T. gondii affects human health. Scientists now believe that the parasite can hitch a ride on white blood cells and steer them toward the brain. There, they coax the brain into producing the neurotransmitter GABA — a chemical linked to lower levels of fear and anxiety. GABA may also play a role in diseases such as schizophrenia. The researchers note that their study does not provide definitive evidence of a link between T. gondii infection and leopard predation. Their study didn't account for the full range of variables that could be affecting chimp behavior, they say. Further, tallying the number of chimps that are killed by leopards in the wild is near impossible. The study was also conducted with a small sample size. “I’d have to file this, at best, in the ‘interesting but nowhere near convincing’ file,” Michael B. Eisen, a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, told the New York Times.

Widespread in Humans

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that roughly 60 million people in the U.S. are infected with T. gondii, which can be acquired by eating uncooked meat, drinking contaminated water, or even from a domestic cat's litter box. In most cases, the infection in harmless and goes unnoticed, as our bodies defenses keep the parasite in check, according to the CDC. But in people with weak immune systems, it can lead to flu-like symptoms, altered risk behaviors and perhaps even schizophrenia. A study published in 2007, for example, linked T. gondii infection in humans with impaired concentration and reaction times — possibly affecting a persona's driving skills. The study in chimps, though conducted on a small scale, serves as further evidence to support a link between T. gondii and its potential to affect human behavior. In today's world, fearlessly approaching house cats carries very little risk. But in prehistoric times, big cats posed a very real threat to our ancestors. The same process that carries the parasite from cats to rats and back again may have played out similarly between ancient humans and predatory felines. In other words, our ancestors may have served as useful vehicles to complete a parasitic circle of life.