Stepping out onto the riverbank, with his fellow travelers watching expectantly and the goats bleating querulously in the canoe behind him, the farmer must have felt a surge of relief. They had paddled 20 miles up the small river from the sea. They had been at sea for weeks or perhaps months before that. Now, stretching before them in this dry season, they saw the river's source, a large lake of clear, sweet water. The low hills around the lake were carpeted with oak and laurel, ash and alder—all the wood they could ever need. And right around the river, sloping gently down to the lakeshore, was a floodplain of silt and clay. The dirt felt lovely and rich in the farmer's fingers. This will do, he thought. Bring the goats ashore. Also the sheep, the large pots of seeds, the flint-bladed sickles and the greenstone axes, the women and children and dogs. The settlers unloaded the contents of what was perhaps a small flotilla of large dugout boats, and they proceeded to do what settlers do. They cleared away patches of shoreline and forest and planted them with wheat and barley. They built huts of wattle and daub, driving foot-thick oak posts seven feet into the ground, for they meant these homes to last. They had no intention of leaving. And that made the settlers quiet revolutionaries: the vanguard of what was arguably the greatest change human history has ever seen. The place is now called La Marmotta; it's a few hundred yards outside the village of Anguillara Sabazia, which is on Lake Bracciano, less than 20 miles northwest of Rome. The time was roughly 5700 B.C., early in the Neolithic Period, five millennia before the founding of Rome. By then, biologically modern humans had lived in Europe for tens of thousands of years. Many archaeologists would call them culturally modern as well, insofar as Lascaux and other painted caves show they were capable of symbolic expression. But another essential human characteristic was still missing in these people. They painted animals, but they did not tame them; they manipulated symbols but not the world. They lived wild, nomadic lives. Like animals, they hunted and foraged. Unlike us, they left the world as they found it. Europe thus remained mostly wild, primeval forest. The change, when it finally came, was so fast and deep it is called the Neolithic revolution. Around 11,000 years ago in the Near East, some people stopped roaming and began farming—domesticating wild plants and beasts, living in permanent settlements. By 9,000 years ago, or 7000 B.C., the revolution had arrived in Greece, and by 4000 B.C., it had spread across Europe into Britain and Scandinavia. Fly over Europe today and you see what the Neolithic revolution has wrought: The land is mostly farms, a tidy patchwork of dun, green, and ochre. On the whole continent, there are but a few tiny islands left of primeval forest. It is difficult to imagine a moment when the situation was reversed, and such farms as existed were islands on the edge of a vast sea of wilderness. That moment is what is preserved at La Marmotta. Since the sixth millennium B.C., as the climate has grown wetter, the water level in Lake Bracciano has risen more than 25 feet, and so the ruins of the Neolithic lakeshore village are now buried in bottom mud 400 yards offshore. For the past decade, a team of divers led by archaeologist Maria Antonietta Fugazzola Delpino, director of the Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography in Rome, has been uncovering those ruins. What Fugazzola's team has found is a large, rich village that was established, she thinks, by pilgrims who had come to central Italy from far away—from Greece or even the Near East. Their settlement survived for at least four centuries before it was abandoned, suddenly and mysteriously, in about 5230 B.C. "Nothing like this has been found in the Mediterranean before," Fugazzola says. "I believe it was a real colony. They arrived here by boat, with animals that were already domesticated and with a large collection of plants. And they found here an ideal place."

At the La Marmotta dig, which archaeologists have divided into five-foot-square parcels using white plastic tubes, a diver vacuums sediment off two of the 3,000 oak posts found embedded in lake-bottom mud. The posts are what held up the houses at La Marmotta, and the large number of them indicates it was a sizable settlement. "This was not just any old village," says archaeologist Maria Antonietta Fugazzola Delpino. "It was something bigger, more important." Photograph courtesy of Soprintendenza Speciale al Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico "L. Pigorini."

Even today Anguillara Sabazia is a surprising bit of paradise. The commuter train from Rome gets you there in 45 minutes; you pass drab apartment blocks and cookie-cutter suburbs before fields and pastures take over at last. Perched on a promontory above Lake Bracciano, Anguillara is a relatively unspoiled pile of medieval houses, cobbled alleys, and curving stairways. On summer evenings, swallows fan out from the old church to fly in crazy circles above the town; conversations and the urgent noise of televisions pour out of open windows; old people cluster on lawn chairs in narrow alleys. From a belvedere lined with blooming oleander on the eastern side of Anguillara, you can gaze out over the cove where Fugazzola's divers are now uncovering the first settlement in this region. Lake Bracciano is a spring- and rain-filled volcanic crater that is just under six miles wide and more than 500 feet deep. It has two outlets. One is the Arrone River—dry this year but navigable in the Neolithic Period—which exits the lake at the end of the cove and curves around to the Tyrrhenian Sea, 20 miles away to the southwest. The other outlet is a man-made aqueduct, the first of which was built under the Roman emperor Trajan in the second century A.D. Fugazzola's staging area, her worktables covered with charts and potsherds, is directly next to an old aqueduct, a few steps away from the Arrone. She and her crew store diving gear near an 18th-century pump house. Fugazzola started working in Lake Bracciano in the mid-1970s. She is a pretty, fiftyish woman with warm, gray-green, slightly droopy eyes, an easy smile, and a soft-spoken manner that does not convey determination—and yet she must have quite a bit. She has become the director of a museum, the president of the Italian Institute of Prehistory and Protohistory, and, in spite of her initial lack of interest, an accomplished diver. "I didn't particularly like either lakes or diving," she says. "But there are many villages submerged under this lake." Most of them, however, date from the Bronze Age or the Iron Age. And though Fugazzola had managed, by the time she got her big break in 1989, to partially excavate a Bronze Age tumulus from the second millennium B.C. at a place called Vicarello, the government had not exactly submerged her in funding. In 1989 the Roman electricity and water authority, ACEA, decided it wanted to build a new aqueduct to tap a strong spring near the center of the lake. It applied to the regional Soprintendenza Archeologica—the government agency responsible for ensuring that Italy's undiscovered archaeological treasures are not carelessly destroyed—for permission to lay the pipe in a trench along the lake bottom. Fugazzola, who then worked for the regional Soprintendenza, dove along the path of the proposed trench with a young colleague, Fabio Faccenna. They saw mud and tall algae and nothing else. They gave ACEA the OK. Italian law requires, however, that an archaeologist monitor construction as it proceeds. One day in April, Faccenna arrived at the site to find that the dredging machine was bringing up large pieces of wood and scattering them on the surface of the lake. He ordered the work stopped immediately. Fugazzola dove into the lake, expecting another Bronze Age site that no one would pay her to excavate properly. She came back to the surface surprised and elated. In the large mounds of mud the dredge had excavated that day and deposited on either side of the 26-foot-wide trench, there were pieces of ceramic along with the wood. Some of those potsherds had distinctive decorations—Fugazzola recognized them right away—made by a potter who had pressed the edges of a cockleshell into the wet clay. That type of pottery had already been found at various archaeological sites along the Mediterranean coast; it's called Cardial pottery, after the cockle Cardium edule. It all dates from thousands of years before the Bronze Age—from the early Neolithic Period. No early Neolithic sites had ever been discovered in central Italy. More important, none had been discovered anywhere at the bottom of a lake. The overlying water and mud, Fugazzola knew, might have protected wood and other fragile artifacts from oxidation and decay, from erosion by wind, and from the depredations of later farmers, who might otherwise have churned the soil. At many Neolithic sites, all you find are potsherds, stone tools, and the post holes that reveal the plan of the houses—the posts themselves and the other wood and plant remains having long since rotted away. Under Lake Bracciano, Fugazzola had a chance of finding something unique in Neolithic archaeology. That summer she and her colleagues spent 40 days picking through underwater mounds of mud the dredge had dug up in a single day. They found lots of wood—huge posts and roof timbers, and also utensils. They found pots that were still full of plant remains. Some of the pots were not decorated with seashell impressions but instead were painted: The yellow-brown clay was striped with reddish, black, or white parallel lines. That was puzzling; painted Neolithic pottery had never been found in central Italy. But it was widely used in Greece during the early Neolithic. The most intriguing find of all that summer was also made of ceramic, but it was no ordinary pot. It was a boat, about 10 inches long. Fugazzola was astonished; model boats were not something that had been reported before in the Neolithic literature, and real boats from the Neolithic were extremely rare and nonexistent in the Mediterranean. After they brought the model boat back to shore, Fugazzola set it adrift in the shallow water next to the pump house. In spite of its high, thick sides, the little boat floated happily; it had been well crafted. "We're going to find some real ones too," Fugazzola remembers saying to herself.

"I'm very brave," jokes Fugazzola, who had limited skills as a diver when she began excavating La Marmotta a decade ago. Along with her breathing apparatus, she carries white polyester paper and a pencil for making underwater sketches.

Ten thousand years from now, maybe there will be archaeologists around to argue about who we were, us modern Americans. Were we descended mostly from recent immigrants from Europe and other places? That would account for the obvious affinity between our culture and the older, European one. Or were we descended mostly from Native Americans who had occupied the North American continent for many millennia—and had then come into contact with Europeans, trading with them and adopting aspects of their culture, such as cities and factories? If all our archives have turned to dust in 10,000 years, both views may seem defensible. Much the same debate has been going on in Neolithic archaeology in recent decades—a debate about the identity of Europe's first farmers and the way in which farming spread across the continent. There is no question that it started in the Near East; the wild ancestors of sheep, goats, wheat, and barley were all native to that region and not to Europe. But were they spread through Europe by immigrant farmers? Or were they acquired through trade and intermarriage by the hunter-gatherers who already lived there? "These people were takers of opportunities," archaeologist Alasdair Whittle of Cardiff University in Wales has written of the foragers, "and could have got wind of changes in settlement, subsistence, and other aspects of life." Whittle and others have argued that it was mostly farming culture that spread across Europe rather than farmers themselves. In the Mediterranean region, however, there is strong evidence that the Neolithic revolution was spread by seafaring pioneers. For one thing, Neolithic sites in the region tend to be near the coast, and some of the oldest are on islands such as Cyprus and Sardinia. For another, the spread seems to have happened very rapidly, especially in the western Mediterranean—so rapidly, according to a recent analysis by Portuguese archaeologist João Zilhão, it must have happened by sea. For a third, we actually have an example of the sort of boat the pioneers may have used. It's on display in the vast entrance hall of Fugazzola's Pigorini National Museum. It took Fugazzola until 1992 to get permission to come back to La Marmotta and begin a formal excavation. She discovered right away that it was going to be hard work. The site was at a depth of 25 feet on the lake bottom, and the artifacts were buried under another 10 feet of dense clay that had been deposited since the Neolithic, after the lake waters had risen. Dredging that clay would inevitably disturb the artifacts; instead, Fugazzola and her colleagues would have to vacuum up the mud with suction hoses. It was near the end of the 1993 season, while preparing to close the site for the winter, that a diver happened on a piece of buried wood that seemed larger than a post or roof timber. It turned out to be much larger—more than 30 feet long. One end protruded from the mud. It looked as if it could be the stern of a boat. What emerged from the mud, after several months of careful vacuuming in 1994, is the 35-foot-long dugout canoe that is now in the Pigorini. Three and a half feet across at the stern, tapering to two and a half at the bow, it was carved from a single massive oak trunk; along the rough and wavy floor, you can see the marks left by stone axes and adzes. (The Neolithic was the last period of the Stone Age, and metal tools didn't exist.) The boatwrights left four transverse stripes of oak, an inch or so high, at intervals along the floor. Those must have acted as ribs to strengthen and stabilize the canoe. Three trapezoidal blocks of wood with holes pierced in them were also found loose in the bottom of the canoe; they may have been used for fastening sails—though the only direct evidence are a few small fragments of fabric found nearby. "These people navigated up and down the Mediterranean," Fugazzola believes. "They knew about sails." They may also have fastened two canoes together to make a catamaran, she says, with a deck of planks. With or without sails, as a catamaran or a monohull, there is no doubt the settlers' canoe was seaworthy, not just lake-worthy. Several years ago, a team of Czech archaeologists led by Radomir Tichy built a copy of it, using replicas of Neolithic stone tools. They proceeded to sail their dugout nearly 500 miles along the Mediterranean coast, from Italy to Portugal. Head winds forced them ashore on occasion. High seas, Tichy recalls, once put them "in a complicated situation. All members remained in the boat, but water was in the boat too." Yet they arrived in Lisbon without serious mishap, convinced that their Neolithic forebears could have made a similar journey, even with goats aboard.

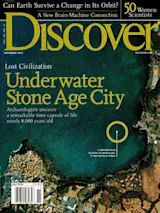

A cove in Lake Bracciano, where La Marmotta is now buried in mud 400 yards offshore, would have shielded Stone Age settlers from heavy winds. Photograph from Space Imaging.

Fugazzola is convinced that the people who settled at La Marmotta had come from across the sea. In addition to the painted pottery, which she says looks like early Neolithic pottery found in Thessaly in northern Greece, she has recently uncovered another striking bit of evidence: a statuette carved in soapstone. It portrays an "abundant woman," as Fugazzola puts it, and it resembles earlier sculptures from the Near East and Greece—sculptures that many archaeologists interpret as representations of a mother goddess. If settlers from one of those places brought their religion to La Marmotta, however, they adapted it to local conditions. Fugazzola thinks the model boats she has found—five so far, the last one just last summer—were neither toys nor mere prototypes. Instead, they may have been ceremonial vessels destined to be set adrift on the lake, filled with offerings for a lake god. The strongest evidence that the Marmottans came from far away is simply that their culture was advanced. At some sites, especially in northern Europe, archaeologists have discovered clear signs that local hunter-gatherers did indeed adopt aspects of Neolithic culture in a piecemeal fashion—sheep or pots, say, but no cultivated plants. But in the region around Lake Bracciano, says Fugazzola, there is no sign of any hunter-gatherers before the settlement was built at La Marmotta. And whoever built the village had at their disposal, from the start, the entire "Neolithic package"—domesticated animals and plants, ceramic pots, polished stone tools—just as if they had unloaded all those things from the boats on the very first day. They did not live off sheep, goats, wheat, and barley alone. They brought pigs and cows with them, too, and two breeds of dog, and they planted a wide variety of crops and collected others in the woods. "They had everything," says Fugazzola. "They ate grains, vegetables, and also lots of fruit—apples, plums, raspberries, strawberries." Especially in winter, they supplemented their diet with acorns, which they stored in large ceramic jars. They cultivated flax to make linen. They planted opium poppies, and whether they used the opium for medicinal or ritual purposes, or maybe just for fun, is difficult to say. Fugazzola has some evidence that they made wine too. It was a big village—Fugazzola's surveys suggest it covered more than five acres. The 3,000 pali, or oak posts, she has found so far give an idea of the scale of the place. The people lived in rectangular houses held up by those posts. The houses were roughly six by eight meters, or 20 by 26 feet, though Fugazzola is now excavating a 32-foot-long building. (It may have served a ritual function; the goddess statuette was found there.) The six or so houses she has dug up so far appear to have been laid out on a single street, which may have been joined at right angles by little alleys. "It was a well-organized village," she says. "There was a plan. It wasn't just a hut here and a hut there." She guesses that maybe 500 people lived at La Marmotta. As the divers dig through the 10 feet of clay that cover the village, the first sign of the plan they come across are the oak posts, still upright in the mud. Between the posts, they uncover a layer of collapsed roof timbers and walls. Finally, they reach a series of several floors, each corresponding to a period of occupation, each one containing the fragmented remains of human life during that period. It is there they find the pots of grains—the Marmottans planted five different kinds of wheat and barley—and the bones of the many different animals, domestic and wild, that the villagers ate. Some pots contain both grains and bones, the remains of Neolithic stew. Scattered among the pots are a large variety of tools. The elegant little sickles with wood handles and blades of flint were made with local materials. But the obsidian, the black volcanic glass that the villagers fashioned into their sharpest knife blades, came either from the Aeolian Islands off Sicily or the Ponza Islands, which are closer to Rome. And the greenstone that they polished into fine ax blades came from northwestern Italy. What such artifacts reveal, Fugazzola says, is that La Marmotta was not, or did not long remain, an isolated outpost on the Neolithic frontier. Centrally located in Italy and the Mediterranean, it may even have been a crossroads for trade. "This was not an ordinary village," she says. "The people were in touch with other communities in the Mediterranean. We picture it as a kind of highway—there were many ships coming and going." That coming and going lasted at La Marmotta for more than 400 years—the tree rings in the house posts confirm that. The outer ring in each post records the year the tree was cut. By comparing many posts and looking for particular years that left recognizable marks in many of them—years of drought or fire, for instance—Orazio Tinazzi of the National Research Center in Verona is pinning down the relative ages of the posts and thus establishing a year-by-year chronology of the village. Eventually, Fugazzola will be able to say exactly how it grew—when each house was built and even when the roof was repaired on one or the room expanded on another. And by combining the tree-ring chronology with carbon dates for each post, she can fix the chronology in absolute time and with great precision. So far, the oldest post Fugazzola has at La Marmotta dates from around 5690 B.C., but she thinks ongoing work may yet reveal the village to have been born a century or so earlier. She is more certain of when it died: within a decade or two of 5230 B.C. The Marmottans abandoned their village then, and judging by what they left behind—valuable tools, pots of food, the large canoe and at least two smaller ones—they left hastily. "Something extraordinary must have happened," says Fugazzola. Perhaps a fire? Or a flood? Whatever it was, it transformed La Marmotta into a ghost town, one that very fortunately was engulfed by Lake Bracciano before it could be reduced to dust.

Above: A 35-foot dugout canoe from La Marmotta on display at Rome's Pigorini Museum was soaked for three years in polyethylene glycol to prevent the wood from disintegrating as it dried. Below: Sheep and goat bones from the dig are the remains of domesticated animals butchered for meals.

The clay laid down by the lake was the savior of La Marmotta; grateful as she is for it, it is also Fugazzola's bane. Each spring, before the real archaeological work can begin on a new section of the site, her team has to spend two months digging through several hundred tons of the hard, compact stuff. Head down in the water, a vacuum hose in one hand, they paw at it with the other, groping all the while in blinding clouds of mud. "When we see the top of the posts, we stop," says Filippo Invernizzi, a graduate student from the University of Florence. Then they wait two or three days for the water to clear. Only then comes the fun part. The divers lay a grid of plastic tubing over the site and begin systematically excavating each five-foot square—slowly now, delicately fingering the mud, and taking care never to set foot on it for fear of causing a work-stopping whiteout. The mud they vacuum up travels to the surface, where it passes through an iron sieve with two-millimeter meshes. The sieve catches things too small for the divers to pick up individually, especially the seeds and other plant remains. As it is, the divers often pick up hundreds of artifacts in a single square. They record the nature and position of each one on waterproof charts; back on shore, two young archaeologists named Giovanna Fois and Laura Benedetti transcribe these jottings onto large master charts. Everybody on the dozen-member team dives, including Fugazzola—although this year, a bad back has sometimes kept her ashore. Time is starting to weigh on her, as it must inevitably weigh on any archaeologist confronted with a dig too vast for one career. In 10 years, Fugazzola has excavated no more than 5 percent of La Marmotta. She would like to complete at least one distinct part of it, but she also must find time to study the material she has found already—and above all, to publish her findings. She has published relatively little so far, and much of it has been in Italian. As a result, even archaeologists specializing in the Mediterranean Neolithic are unfamiliar with the site. Some of them are frankly skeptical about Fugazzola's claim that its inhabitants came all the way from Greece or the Near East. How long will Fugazzola continue to dig? "You know, my back hurts," she says, "and I'm old." Which is not quite true but true enough to make it fortunate that she is training the next generation. Invernizzi is doing his Ph.D. on the wood artifacts of La Marmotta, and his biggest problem is that he has nothing to compare them with. "This is unique material in the world," he says. Laura Benedetti has been diving at La Marmotta for nine years and has not yet tired of it. "The emotion—I don't know if I can describe it," she says in halting English. "When you dive down, it is like you can read a book of the past. We see everything. We see their food! It is an extraordinary site."

Anguillara Sabazia, a medieval village, overlooks the cove where La Marmotta lies 25 feet underwater. Established more than six millennia after the demise of La Marmotta, the hilltop settlement now thrives on summer tourism, though no recreational boating is allowed. The posts in the water are a barricade erected by commercial fishermen who catch coregone and luccio, deepwater fish that are rare regional delicacies.

The Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography Web site: www.pigorini.arti.beniculturali.it.