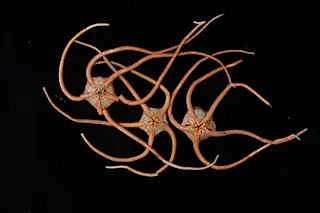

A scanning electron microscope image of an American house dust mite. Our world is quite literally lousy with parasites. We are hosts to hundreds of them, and they are so common that in some ecosystems, the total mass of them can outweigh top predators by 20 fold. Even parasites have parasites. It's such a good strategy that over 40% of all known species are parasitic. They steal genes from their hosts, take over other animals' bodies, and generally screw with their hosts' heads. But there's one thing that we believed they couldn't do: stop being parasites. Once the genetic machinery set the lifestyle choice in motion, there's supposed to be no going back to living freely. Once a parasite, always a parasite. Unless you're a mite. In evolutionary biology, the notion of irreversibility is known as Dollo's Law after the Belgian paleontologist that first hypothesized it in 1893. He stated ...

Irreversible Evolution? Dust Mites Show Parasites Can Violate Dollo's Law

Discover how house dust mites surprisingly abandoned a parasitic lifestyle, challenging long-held beliefs in evolutionary biology.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe