Evolutionary biologists have long been interested in the dimensions of the human noggin, and more specifically the size of the brain tucked inside. The human cranium is so big, they point out, that it poses risks during childbirth, and it takes a lot of energy to keep that big brain humming along. Most researchers assumed that the large size must deliver a major evolutionary advantage, like the capacity for increased intelligence, to make up for these disadvantages. Now a study published in Nature Neuroscience [subscription required] suggests that it wasn't an increased number of brain cells that gave humans such an evolutionary boost, but rather the increased complexity in the synapses between brain cells.

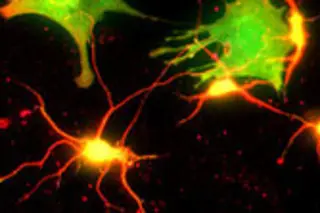

[Synapses are] the junctions between nerves which transfer electrical signals -- and information -- from one brain cell to the next via a series of biochemical switches. Most research to date has assumed that synapses, made ...