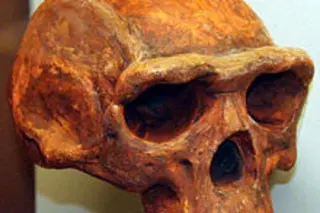

Credit: Thomas Roche By now you have probably seen the articles about how a new skull has transformed our understanding of the human family tree. The original paper is at Science, A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo. More colorfully you might say that this publication burns down the "bushy" model of human origins, where you have a complex series of bifurcations and local regional diversity, and then rapid extinction with the rise of H. sapiens sapiens ~50,000 years ago. In general I'm more in agreement with those plant geneticists who are skeptical of excessive fixation on the concept of species, so this is not a shock to me. To me a species concept is not a thing, but an instrument to a thing (i.e., I'm in interested in population and phylogenetics). The reason these sorts of findings overturn the orthodoxy has more to ...

If these bones could talk

Discover how the Dmanisi skull transforms our understanding of the human family tree and the evolutionary biology of early Homo.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe