It's a warm September morning in the year 2019, and you snap on NPR's Morning Edition to catch a few minutes of the news before biking off to work. But an older and wiser Steve Inskeep has grim news for you today. The Global Extinction Awareness System, a supercomputer that accurately predicted the extinction of red squirrels several years ago, has run the numbers for our own species through the computer, and our odds of survival aren't good. According to GEAS, Homo sapiens may go extinct by the year 2042.

That's the scenario that greets players in the forthcoming online game Superstruct, which is being run by the think tank Institute for the Future. Beginning on September 22^nd, players will be invited to plunge into the troubled world of 2019, and to begin to work towards solutions that could buy our species a little more time on the planet. They're forced to cope with five "super-threats" that are wearing down our civilization, including devastating outbreaks of a pandemic respiratory disease, climate refugees who have fled homelands made unlivable by global warming, and legions of hackers who exult in bringing down global information networks.

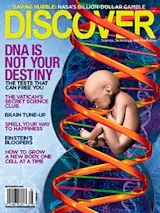

Image courtesy of Institute for the Future

But this isn't just a chance for gamers to flirt with the dark edge of disaster; they'll also be participating in a cutting-edge experiment that tries to harness the wisdom of crowds for a higher purpose. Superstruct is what the institute calls the world's first "massively multiplayer forecasting game." The Institute for the Future doesn't like to put it this way, but it's essentially trying to use crowdsourcing to predict the future.

The Palo Alto-based institute doesn't have a problem with the crowdsourcing lingo; distributing creative work to the masses is all the rage these days. It's the idea that the institute tries to predict the future that raises hackles. While the non-profit institute does keep itself afloat largely by selling its 10-year forecasts to corporations who are very interested in what the future may hold (and what it augers for their brands), institute employees say that forecasting is a very different thing than prediction.

"Future forecasting is all about testing strategies—it's like a wind tunnel," says Jamais Cascio, one of the game directors for Superstruct. "We create scenarios with different kind of challenges that may come to pass, and you cantest your strategy." Now, instead of having that wind tunnel be designed and constructed by what Cascio calls "our little hermetic cabal of thinkers," the institute is handing the toolbox to the unruly mob. For a think tank that has taken pride in doling out expert opinions, giving control to the multitudes is a dramatic step.

The idea of using the masses' collective intelligence to peer into the future isn't new; prediction markets (modeled after stock markets) already exist to let people bet on the possible success of presidential candidates, sports teams, and Hollywood blockbusters. But such prediction markets can only get you so far, says Jane McGonigal, another of the game's directors, because they can only ask questions in which the entire range of outcomes has already been determined. "We want to ask questions where we have no idea of the range of outcomes," McGonigal says. In Superstruct, the players will be presenting their ideas on how to cope with the crisis of 2019, and McGonigal hopes they'll come up with solutions and outcomes that she never imagined. "That's why the tagline for the game is 'Invent the Future,'" she says. "Because the future doesn't just happen, somebody makes it."

The game came together quite naturally, explains Kathi Vian, director of the institute's Ten-Year Forecast Program. The institute wanted to join the open source revolution and experiment with more participatory methods of forecasting. Cascio, a futurist and scenario planner who often works with the institute, wanted to give people a venue for brainstorming ideas, in the continuation of a mission he began five years ago when he co-founded Worldchanging, a popular publication about environmental solutions.

Superstruct's other mastermind is the institute's resident game designer, Jane McGonigal, who joined the think tank several years ago because she "takes play seriously" and believes that impassioned gamers can accomplish amazing things. She has previously worked on a game that asked players to role-play their way through an oil crisis. And she's fresh from directing a triumphant alternate reality game that was sponsored by McDonald's and the International Olympic Commission as a promotion for the Beijing Olympics, in which she convinced players on every continent except Antarctica to run labyrinths blindfolded in order to save the world.

The team called the new game Superstruct because "society's existing structures and organizations aren't up to the incredible challenges facing us in the 21^st century," Vian says, and players will have to build new structures on top of the old. The threats the players will confront are based on the institute's own research about how things could go horribly wrong for humans over the coming decades. "There are some scenarios out there that talk about the real threat of human extinction by the end of the century," Vian says. "So the circumstances present in the game world are a little exaggerated, but it's a plausible worst-case scenario."

This isn't the kind of game where your avatar whips out a magic potion to ward off a bad case of bird flu. Instead, players will essentially imagine themselves into the future, and will tell other players what they're seeing, feeling, and doing through blog posts, videos, or whatever medium suits their purposes. And while there will be some traditional game elements, such as missions to accomplish and points to win, it can just as easily be viewed as a kind of "collaborative storytelling," Cascio says.

"You've heard of LARPs—live action role-playing games—where people run around in capes, saying, 'Lightning bolt! Lightning bolt!'" he says. "This isn't quite that bad, but this is in some respects a LARP. We're asking you to take on the role of yourself, some years from now, and live in that moment for awhile," says Cascio (who admits that he learned a lot about managing people by acting as the God-like dungeon master while playing Dungeons andDragons).

In Superstruct, players will bring their own personal knowledge and experiences to the table. "We don't need everybody to be experts on how climate might change and how the economy might be impacted," says McGonigal. "If you're a teenaged girl, tell us how a teenaged girl would respond to this crisis. We need that personal intelligence from everybody." The players will help imagine and document the world of 2019, and will work together to come up with solutions to the challenges that are presented throughout the six-week game. Cascio says that his highest hope is that the collaborating players will come up with innovative ideas that have applications here, in the real world of 2008. "The mass of ideas can become almost an epiphany engine," he says.

The game is projected to have a couple of different payoffs for its sponsor: It will test this method of crowdsourced forecasting and will produce scads of ideas that might make it into the institute's expert-produced 10-year forecast.

But Cascio says the players—even the world at large—may reap a greater reward from playing Superstruct. "A lot of the challenges we're dealing with this century have a very long lag time," Cascio says. "Even if we were to stop putting out greenhouse gases right now, we'd still face decades of warming." Most humans aren't in the habit of acting on consequences they can't see, he says; they have to be coaxed into saving money for retirement or into supporting climate change legislation that will raise energy prices.

"According to some neuroscientists, our capacity for long-term thinking emerged in the parts of the brain that were initially involved with throwing rocks at moving objects," a skill first developed further during harsh ice ages, Cascio says. "If you look at the major advances in the Hominid line—advances in tool use, language, and art—most of these were triggered by environmental changes," he says. "Foresight turns out to be a critical adaptive strategy for times of great stress."

There's little doubt that our world is under stress, and a little human evolution right now could help a lot. Cascio, McGonigal, and the institute are banking on the idea that a game can get people into the habit of thinking far into the future. If all goes well in the game world of 2019, players may realize that for thes pecies to survive, we must all become futurists.