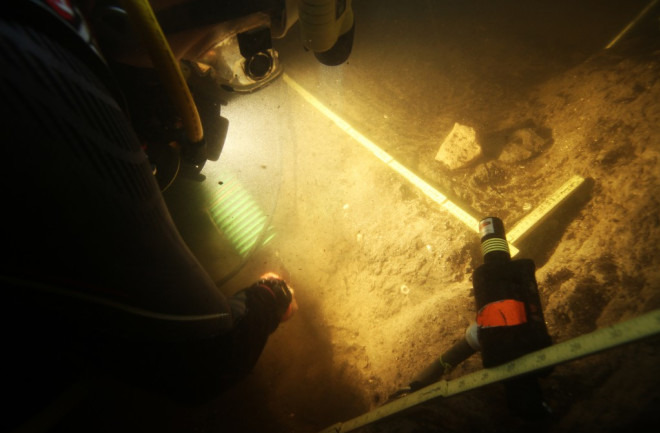

The challenging Page-Ladson archaeology site, the oldest evidence of humans in the southeastern U.S., is 30 feet underwater with zero visibility. Only a handful of archaeologists across the continent have the skills — and the fortitude — to do the careful, laser-guided excavation work. Credit: S. Joy, courtesy of CSFA. Out of murky water comes a clearer picture of when the Americas were populated. Numerous 14,550-year-old finds from 30 feet underwater in a Florida river represent the oldest archaeological site in the southeastern U.S. — and the latest direct challenge to one archaeo-camp's long-standing belief about when the first people arrived on the continent. The site yielded stone tools, including a knife-like cutting implement, and a mastodon tusk with cut marks that suggest it was butchered by humans eager to get at the highly nutritious tissue in the tusk's pulp cavity. Yum. The Page-Ladson site, in the Aucilla River near Tallahassee, was first excavated in the 1980s and '90s. Those early digs yielded some tools and the mastodon tusk, all dated to more than 14,000 years ago. Mainstream archaeologists at the time scoffed at the results because the prevailing theory — until fairly recently — was that the Americas were first settled around 13,000 years ago by the Clovis people, known from distinctively shaped tools and projectiles found at locations across much of the continent.

First Americans: Underwater Butchering Site Dices Timeline

Newsletter

Sign up for our email newsletter for the latest science news

0 free articles left

Want More? Get unlimited access for as low as $1.99/month

Stay Curious

Sign up for our weekly newsletter and unlock one more article for free.

View our Privacy Policy

Want more?

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Already a subscriber?

Find my Subscription

More From Discover

Stay Curious

Subscribe

To The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Copyright © 2025 LabX Media Group