It is hard to think of a larger catastrophe than a gigantic volcanic eruption. The day is turned to night, seering hot clouds of ash and debris roar down, the earth shakes constantly and the landscape is buried. That's just the local impact. Globally, a giant blast might send ash around the planet and cool the climate for years at a time. You'd think it would be hard to miss the evidence of such volcanic events.

Yet, the geologic record is incomplete. The power of erosion and transport can take thick deposits of ash and erase them (or at least move them). New eruptions can bury the evidence of those that came before. The tell tale signs of such fury can be obscured so that what might have seemed like armageddon at the time is lost to history.

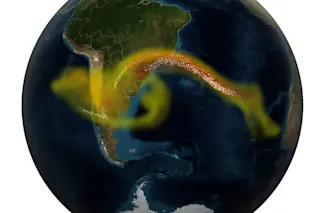

Luckily, we don't need to only rely on the rock record to ...