Our relationship with yeast is like a college friendship that grew beyond keggers and into distinguished adulthood. We’ve partied with our eukaryotic wingmen dating back to at least 7000 B.C., using them in foods and head-spinning libations. In 1680, Anton van Leeuwenhoek, godfather of microscopy, gazed upon yeast for the first time; that’s when we started moving past the party years.

We still throw down with yeast, but we’ve grown up and have jobs now. These days, the fungus is a laboratory champion, an engine of industry. It underpins Nobel Prize-winning breakthroughs and churns out biofuels and novel medicines. Indeed, yeast may someday save our lives.

What Is Yeast?

There are over 1,500 species of yeast. The microscopic, single-celled, eukaryotic fungus is found everywhere, and we know it well. Beer barons control its evolution, and scientists fiddle with its DNA. One-third of yeast genes have counterparts in the human genome, many of which are associated with diseases, such as cancer. And given that yeast is inexpensive, reproduces quickly and is easy to work with, it’s the most well-studied organism known to humans.

Winning Nobel Prizes

Yeast is basically the MVP of lab organisms. It’s helped scientists claim five Nobel Prizes in the 21st century (2001, 2006, 2009, 2013 and 2016). Yoshinori Ohsumi, the most recent prizewinner, used baker’s yeast to identify genes crucial in autophagy, the process by which cells recycle their components. Diseases like Parkinson’s, Type 2 diabetes and cancer have been linked to disruptions in this cellular recycling process. The autophagy machinery in yeast cells is similar to that in human cells, and Ohsumi’s work, which began in the 1990s, gives scientists new targets for possible treatments.

BioSentinel Mission 2018

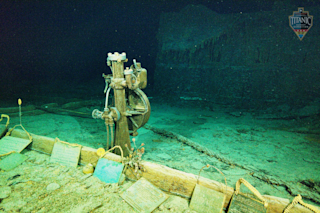

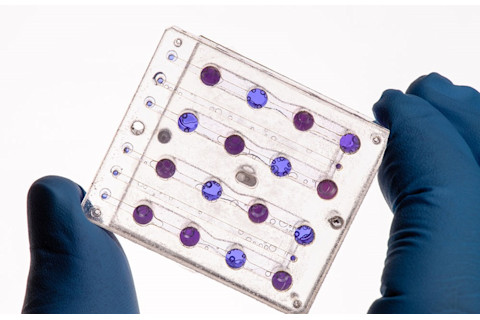

Planned for launch in July 2018, NASA’s BioSentinel spacecraft (below) will expose yeast to the ravages of interplanetary radiation. Cards dotted with a series of microwells housing three strains of yeast will be activated (via a hydrating injection) at different points along an 18-month timeline. Scientists will track the yeasts’ growth and metabolic activity.

The experiment will be replicated aboard the International Space Station and on Earth for comparative samples. It’ll be the first experiment elucidating the biological effects of radiation beyond low Earth orbit in over 40 years, according to NASA.

(Credit: NASA)

NASA

Pasteur’s Revenge

Soaked in the vinegar of defeat after the Franco-Prussian War, French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur vowed to avenge his homeland by hitting the Germans where it hurt: the beer.

A pioneer of immunization and food sterilization, Pasteur (below) also experimentally proved in the 1850s that yeasts drove the fermentation process, gobbling sugars to produce ethanol, carbon dioxide and a host of other compounds essential to beer. He identified microbes that could spoil a batch of beer and devised methods to keep them out, preventing contamination and enhancing beer’s flavor.

By the time the war broke out in 1870, Pasteur, jaded by personal losses, forbade publishing his brewing secrets in German, hoping to give French brewers enough scientific artillery to threaten Germany’s chokehold on the industry. Pasteur wanted France to produce the world’s finest beer, or what Pasteur dubbed “the beer of revenge.” His work inspired a generation of beer barons, including J.C. Jacobsen, who founded Carlsberg in Denmark.

In the 1880s, scientist Emil Hansen isolated a yeast strain and named it Saccharomyces pastorianus in homage to Pasteur — a man who, reportedly, didn’t even like the taste of beer.

Louis Pasteur (Credit: Wellcome Library)

Wellcome Library

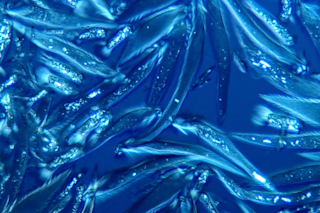

Spider Silk

In the lab at Bolt Threads in Emeryville, Calif., technicians are using yeast enhanced with spider DNA to brew silk proteins that are spun into textiles. Bolt researchers control fabric qualities, like stretch and softness, by manipulating protein chemistries, fermentation conditions and other aspects of the spinning process. In 2016, the company received $50 million to scale up production, even partnering with apparel company Patagonia to develop designer products.

Ties from Bolt Threads. (Credit: Bolt Threads)

Bolt Threads

DNA Slipping

We’ve been slipping foreign DNA into yeast since 1978, when Gerald R. Fink at MIT figured out how. In 2015, scientists swapped genes crucial for yeast survival with human versions, and of the 414 genes they tested, nearly 50 percent of the human proteins could keep the yeast alive.

Today, yeasts are programmed to secrete human proteins used in vaccines, insulin and other biopharmaceuticals.

Gross Yeast Tricks

Beard Beer, from Oregon-based Rogue Ales, is brewed with a strain of wild yeast harvested from nine beard hairs plucked from brewmaster John Maier. The Baltimore Sun said the American wild ale has a “smooth finish and citrus notes.”

In 2015, British blogger Zoe Stavri reportedly baked a sourdough leavened with yeast from a vaginal infection — granted, it was a very small amount. Candida albicans, the typical culprit behind such infections, likely played a role in this baking project. Doctors do not advise repeating this at home.

Biofuels

We’ve used yeast to convert plant cellulose and starch into biofuels like ethanol for decades; however, the process still isn’t efficient, and scientists are genetically altering yeast to change that. Yeast doesn’t function well in high alcohol concentrations, so upping its resistance is one objective. Also, coaxing yeast to move beyond glucose to sugars found in non-food plant fibers could lower costs.

As it stands, 90 percent of car engines still run on petrol, as opposed to alcohol.