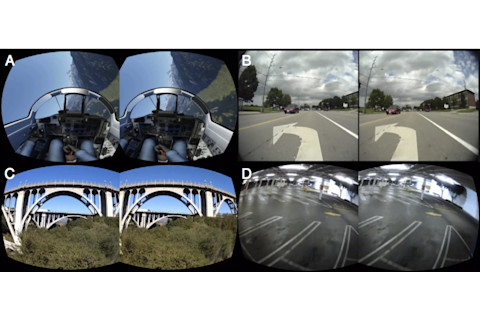

Between the rise of 3D movies and virtual reality, more and more people are getting a chance to don goofy glasses or headsets and experience media in three dimensions. And many of those people are discovering something about themselves: 3D makes them ill. Sitting in the theater or on their own couch, they get a sensation like motion sickness. They might feel nausea, dizziness, or disorientation. A new study suggests that these symptoms aren't weakness on the part of the viewer. People who get "simulator sickness" may simply have better 3D motion perception. Several factors influence whether a person is prone to ordinary motion sickness. Studies have found that younger people are more vulnerable, and that more women get motion sickness than men. Certain personality traits have also been tied to motion sickness. The main theory behind why it happens, though, is that the brain is getting conflicting cues. Say a person is trying to read in the car, for example. Maybe the eyes, trained on the pages of a book, report that the body is staying still, while the inner ear is pretty sure it's speeding along a highway. C. Shawn Green, a psychologist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and his colleagues used that idea of conflicting cues to study 3D sickness. Maybe, they reasoned, certain people are more sensitive to this conflict because their senses are more accurate. A brain that builds a very precise picture of the world around it might be quicker to notice when sensory cues don't quite line up. In brains that aren't so particular, maybe a little bit of mismatch goes unnoticed. In a fake 3D environment, there are plenty of chances for cues to conflict. Maybe a character appears to be moving toward the viewer because it's getting larger, for instance, but the viewer's eyes don't need to refocus like they would in real life. This mismatched information could cause mayhem in an attentive brain. To test the idea, the researchers gathered 84 subjects and gave them a battery of visual tests. The tests measured their 3D vision, both for moving objects and stationary ones. Then subjects watched 3D videos in an Oculus Rift headset for 20 minutes. These weren't true virtual reality settings, where people can turn their heads to look around within an environment. They were straightforward 3D movies that gave a first-person view of driving a car, swooping through a canyon in a fighter jet, or flying as a drone. After watching the movies, subjects filled out questionnaires about how they felt.

The 3D videos. Not everyone survived the full 20 minutes of 3D videos, though. Sixty-three percent of subjects quit before the end. They complained of symptoms like nausea, headaches, dizziness, and eye strain, Green says. The researchers looked for differences between quitters and the rest of the group. People who quit early were more likely to be women. The quitters reported being more prone to motion sickness in their everyday lives. They also had better 3D motion perception. Green says this is the same visual skill you might use in real life to judge the distance of a baseball or soccer ball that's coming toward you. When the researchers looked across all subjects, they saw that people with better 3D motion vision reported feeling worse after watching the movies, even if they hadn't quit. Even the difference between the sexes could be traced back to the same thing: the women in the study group had tested higher for 3D motion perception, making them more likely to feel sick and quit the experiment. This points to an "interesting paradox," the scientists write: "those who have better 3D vision, and thus would be able to take the most advantage of 3D technology, are also those who are least able to tolerate it." The results do suggest ways to make 3D movies and games more tolerable to their viewers. If creators were more careful about cues for 3D motion, creating environments that were a more perfect match for the real world, they might make fewer people feel like vomiting. Green says the finding fits with the broader theory of motion sickness, too. The kinds of mismatches experienced by a person who's trying to read in a car aren't quite the same as a person shooting aliens in a 3D video game. But that person's sensitivity to sickness might also depend on how accurately her brain observes those cues. And a better understanding of motion sickness might one day help keep all of us less queasy—in the real world or not.

Images: top by Sergey Galyonkin (via Flickr); bottom, Allen et al.

Allen, B., Hanley, T., Rokers, B., & Green, C. (2016). Visual 3D motion acuity predicts discomfort in 3D stereoscopic environments Entertainment Computing, 13, 1-9 DOI: 10.1016/j.entcom.2016.01.001