This is the third is a series of three posts from researchers’ expedition to northern Norway. Read others in the series here.

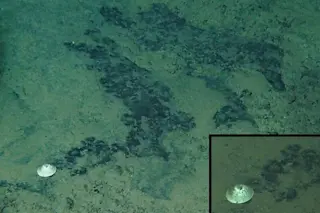

As fieldwork drew to a close last week off the northern tip of Norway, stormy seas flattened to a silvery smoothness and hungry fulmars swam about our fishing boat waiting for juicy leftovers. All we had to offer, though, were dead shells. The team of scientists I accompanied had still not achieved one of its prize goals: the discovery of live, deep-water clams of a very special kind. The confidence we brought at the beginning of the week was wearing thin. Dead shells dredged from 600-foot depths proved our prey were tantalizingly close, but elusive. For days we had successfully collected living samples in 50-foot waters, but the Arctica islandica clam, the oldest living multicellular animal in the world, is at the extreme reach of its range where ...