Our understanding of animal minds is undergoing a remarkable transformation. Just three decades ago, the idea that a broad array of creatures have individual personalities was highly suspect in the eyes of serious animal scientists — as were such seemingly fanciful notions as fish feeling pain, bees appreciating playtime and cockatoos having culture.

Today, though, scientists are rethinking the very definition of what it means to be sentient and seeing capacity for complex cognition and subjective experience in a great variety of creatures — even if their inner worlds differ greatly from our own.

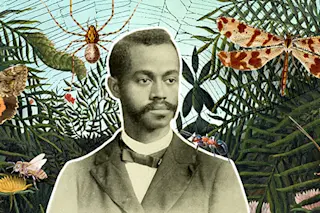

Such discoveries are thrilling, but they probably wouldn’t have surprised Charles Henry Turner, who died a century ago, in 1923. An American zoologist and comparative psychologist, he was one of the first scientists to systematically probe complex cognition in animals considered least likely to possess it. Turner primarily studied arthropods such as spiders and bees, closely ...