Don’t you just hate it when a moth larva busts in through the wall of your house like some squirmy lepidopteran Kool-Aid man?

If you’re a colony of aphids living in a gall, this is a real threat. But luckily there’s a team of heroes ready to spring to action, even sacrifice themselves, to repair that wall and save the rest of the clan.

A team of Japanese researchers has been studying this phenomenon for over 15 years. Their latest work, out this week in PNAS, breaks down the interesting chemical properties of the sticky spackle the aphids use to patch the hole. But the coolest part might be how well the phenomenon mirrors a body’s immune system.

Bug Off

Some species of aphids, little insects that suck sap out of plants, live in colonies inside galls.

A gall is an abnormal growth on a plant, similar to tumors in animals. Gall formation is triggered by chemicals secreted by an intruder like a virus, bacterium, fungus or insect — including aphids who intend to move inside.

Some other insects don’t make galls but steal ones that are already in use. One such kleptoparasite — or biological home invader — is the nolid moth (Nola innocua), whose larvae steal galls from aphids called Nipponaphis monzeni.

Though the moth larva doesn’t attack the aphids directly, the act of it boring into the gall and eating it from the inside-out tends to leave all the aphids, well, dead.

The aphids don’t give in so easily. They'll attack the larva. And as soon as a hole is bored into their gall, a team of aphid nymphs — or juveniles — from the colony immediately surround it.

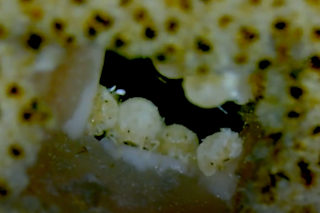

They discharge a surprising volume of white fluid that looks a bit like Elmer’s glue, which they knead as it congeals and hardens, plastering the hole. They lose up to two thirds of their body mass. The secretion contains whole globular cells called hemocytes, some of which burst outside the body to add more to the plaster. (You can watch a video of it here.)

Some of the aphids get plastered right into the patch in the wall. Others might be abandoned on the outside, no longer able to get back in. Those that “survive” will likely die from the extreme loss of bodily fluid. After the aphids install their patch, the plant actually regrows more tissue, healing the gall.

As the nymphs knead the fluid, it hardens to form a patch, which will eventually regrow with plant tissue. (Credit: Mayako Kutsukake)

Mayako Kutsukake

A Social Immune System

The researchers describe what happens as a “coagulation” of aphid bodily fluids which form a “scab” over the gall’s injury.

If this reminds you of the last time you scraped your knee, it should. In the bodies of mammals, blood cells called platelets will gather at a wound right after injury. These stick together to form a clot, preventing more blood loss from the site. Other cells and molecules that make up the immune system spring to action to stop any intruders, like bacteria that might have entered with the scrape.

The aphid system to protect their gall is surprisingly analogous — a “social immunity.”

This is neat because immunology normally focuses on the cellular and molecular ways a body fights off intruders, explained Takema Fukatsu, who lead the study, in an email.

But in social animals, there can also be behavioral, physiological, even social organizational ways that a so-called immune system can function — for the survival of the group as a whole.

But in the aphids, the group discovered, the “individual immunity” and “social immunity” were not separate ideas, but connected by evolution. They think the body fluid the aphids secreted to plug the hole could have evolved from body fluids that would heal a wound inside an individual aphid.

Fukatsu is senior researcher at Japan’s National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology and a professor at the University of Tokyo and the University of Tsukuba.

He explained, “the mechanistic bases of social immunity … are expected to be distinct from the molecular and cellular immune mechanisms. In this context, our finding was quite unexpected and surprising.”

“The phenomenon and the behavior are extremely exciting,” says Fukatsu.