Of the questions that have troubled great thinkers these last few thousand years, the question of which TV science show is the best has proved among the hardest to resolve. This is partly because the science shows on television keep changing, but it is also a fact that work in the field has, until lately, been spotty and lackadaisical, undertaken more often by desperate science writers for an afternoon than by a dedicated specialist for an entire year. I want to thank the editors for giving me the time and space to pursue my own research to its full completion. Without further ado I can now reveal the best science show on television: Ghost Hunters, currently in its fifth preposterous season on cable television’s Syfy (né Sci Fi) Channel.

“No, it isn’t,” I hear you protest, and you have my sympathies, for that was my first reaction too. Like you, I subscribe to various high-end periodicals, where much has been written in recent years about the current golden age of science on television, and Ghost Hunters does not often get a mention. For Virginia Postrel, writing in The Atlantic back in 2007, it was dramas like

and

Numb3rs

that were making braininess sexy and imparting a “geeky glamour” to the airwaves—and that was before the rise-to-total-dominance of House, a prime-time juggernaut whose climax each week involves a man having a scientific epiphany illustrated by an animated sequence of a corpuscle misinterpreting a hormonal signal from a gland. On the nonfiction side of the ledger, the pasture is even lusher and more science-y. Even aside from your

and your How It’s Made, there are now entire channels whose raison d’être is to let people watch planets spinning and nebulas…nebulizing, all in high definition at four in the morning.

How is it, then, that the best science show on TV turns out to be a low-budget and in many ways deeply stupid offering about two Roto-Rooter plumbers who spend their weekends shuffling around old buildings in the dark, interpreting every distant thump as a “footstep” and every draft-powered swish of a curtain as a lonely dead child whispering “Chrisss”?

Well, it is certainly not that the Ghost Hunters make braininess sexy; no, for that they would need more braininess. Lead investigator Jason Hawes, founder of the Atlantic Paranormal Society, not only looks like and has the same day job as Samuel “Joe the Plumber” Wurzelbacher but carries himself with the same air of surly distrust, as if suspicious that the whole world might be encoded with hilarious bon mots at the expense of his sister. Hawes’s sidekick, Grant Wilson, is a slighter, stooping man with a Dickensian underbite and a permanently queasy expression, as if he’s about to be hanged for stealing a sheep, and like Hawes he is approaching midlife without entirely having mastered the difference between phenomenon and phenomena. Those hoping against hope that the pair might be closet intellectuals were cruelly disabused in one recent episode when, upon rolling up to the supposedly haunted former home of novelist Edith Wharton and finding it to be a huge mansion, Jason squinted up at the crenellated frontage and, in lieu of a low whistle, murmured to Grant: “Yeah. I’m thinking she was a pretty good author.”

It also needs admitting that the Ghost Hunters, while unflaggingly vocal in their allegiance to “science” and “hard evidence,” might want to avoid investigating the haunted former homes of Karl Popper, say, or Ernst Mach, lest something throw a lamp at them. Investigations begin “scientifically” enough. Jason and Grant arrive at a location at dusk with a vanload of equipment and listen carefully, even skeptically, to the proprietor’s account of the various black masses, white ladies, and mustachioed gentlemen seen wandering about the place. Their team of young assistants then festoons the property with infrared cameras and digital voice recorders, and for the rest of the night the team shuffles about in groups of two using handheld devices to measure unexplained changes in temperature and fluctuations of electromagnetic fields (knowingly shortened to “EMF”). Electromagnetism, of course, is one of the most science-y things around, but one is best advised to have a reason to measure it before one goes out and buys a fancy meter. “There is a theory,” either Jason or Grant will explain afresh to the camera in most episodes, that anomalous EMF readings can indicate the presence of paranormal activity. But after five long seasons of watching EMF levels randomly soar and plummet in the darkness, it has been revealed to be a theory of exceptionally low quality. Yet they cling to it still.

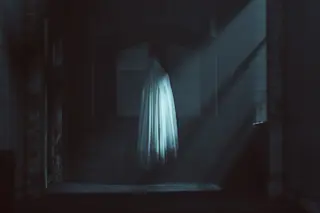

The key scientific concepts of falsifiability and repeatability are missing from the Ghost Hunters’ arsenal. Upon hearing a distant thump in an old wooden house as its timbers settle for the evening, Jason and Grant will, quite properly, call out, “Can you do that again, please?” and after a respectful pause of maybe 45 seconds, the spirit will often oblige, typically from a different part of the house, causing much dropping of jaws and widening of eyes. But never is the spirit asked to thump four times slowly, then shut up for a minute, then give them 13 thumps in quick succession. More maddening still, in the event that their cameras do actually capture a mysterious moving shadow or the faint outline of what just might be a Civil War–era soldier with one leg and an exceedingly peaked cap, Jason and Grant will share the news with the homeowner, then drive away in their SUV, congratulating each other on “another great investigation.” I do not concur with this analysis. To qualify as even an adequate investigation, the Ghost Hunters would surely return the next night, perhaps even the night after that, maybe every night for a week, until rather than a blurry photo of a possible ghost they had a tack-sharp photo of an actual one. Instead, the more promising and intriguing their findings, the more likely the episode is to be the last in the series, to the immense frustration of any actual scientists watching.

Finally, there is the Ghost Hunters’ peculiar habit of turning out all the lights before investigating. If it is ever proved conclusively that death is not the end, but that we live on inside walls of creepy old buildings, disembodied but in period costume, someone is winning a Nobel Prize. There would be no more glorious spectacle—trust me—than that of Jason and/or Grant and/or the tattooed, phlegmatic tech manager Steve Gonsalves in white tie addressing an auditorium of Swedes on the best techniques for gathering “electronic voice phenomen…” and then discreetly swallowing the last syllable. Which is why it is so frustrating to see them pursuing such important work in total darkness. I could understand it if witnesses reported seeing ghosts only in the pitch black, but they don’t. From the data gathered over five long seasons, it would seem one is at most heightened risk of a paranormal encounter when one is either “locking up for the evening, you know, like I always do” or “just sitting there, watching TV.” Yet rather than replicate these at least partly illuminated conditions, the Ghost Hunters insist on “going lights-out,” with all the attendant risks of stumbling, falling, or getting creeped out. If Isaac Newton had worked only at night, it is hard to imagine he would ever have unpacked light into its spectrum of component colors. Why, then, must the Ghost Hunters work in darkness?

Because to Jason, Grant, and the rest, darkness is their ultimate quarry—and here is where the scientific juices begin to flow. If the impossible one day were to happen and they found themselves with high-def footage of Edith Wharton making out with a headless horseman in a hammock of ectoplasm, it would most likely be an annoyance to them, a distraction. Ghost Hunters is the best science show on television because unlike the fastidious drones of CSI or that frizzy savant on Numb3rs, the Ghost Hunters never win, and they don’t care.

For Jason and Grant there is clearly no greater thrill than reporting back to the owner of some massively atmospheric and turrety castle that the voices he’s been hearing are from his glitchy clock radio and that the place is as haunted as a tube of toothpaste. And we, their fans, are with them on that. For it is not ghosts we tune in to see. We tune in to see Jason spend 20 minutes latching and unlatching a closet door to find out why it swung open. We tune in to watch Steve and his callow protégé, Dave Tango, hunched exhaustedly in an Econo Lodge room, growing stubblier before our eyes as they “review” hours of low-grade audio for that moment when, amid an ocean of hiss, a disembodied voice might just possibly be saying “Chrisss.” We tune in to be reminded of what CSI, House, and the rest will never remind us: how easily and thoroughly any humdrum human existence can be transformed if you wrest your attention from the tawdry Technicolor scenery of life and train it instead upon the murk and gloom and the shadows that surround us.

Other shows might be more movingly persuasive on the thrill of finding answers, but Ghost Hunters, uniquely, can sell you on the thrill of having questions and of proceeding—carefully and with senses peeled—ever deeper into the endless, exhilarating dark.