Helen Epstein felt deeply isolated and alone. Haunted by her parents’ harrowing experiences in Nazi concentration camps in World War II, she was troubled as a child by images of piles of skeletons and barbed wire, and, in her words, “a floating sense of danger and incipient harm.” But her Czech-born parents’ defense against the horrific memories was to detach. “Their survival strategy in the war was denial and dissociation, and that carried into their behavior afterward,” recalls Epstein, who was born shortly after the war and grew up in Manhattan. “They believed in action over reflection. Introspection was not encouraged, but a full schedule of activities was.”

It was only when she was a student at Israel’s Hebrew University in the late 1960s that she realized she was part of a community that shared a cultural and historical legacy that included both pain and fear. “I met dozens of kids of survivors,” she says, “one after the other who shared certain characteristics: preoccupation with a family past and Israel, and who spoke several middle European languages — just like me.”

Epstein’s 1979 book about her observations, Children of the Holocaust, gave voice to that sense of alienation and free-floating anxiety. In the years since, mental health professionals have largely attributed the second generation’s moodiness, hypervigilance and depression to learned behavior. It is only now, more than three decades later, that science has the tools to see that this legacy of trauma becomes etched in our DNA — a process known as epigenetics, in which environmental factors trigger genetic changes that may be passed on, just as surely as blue eyes and crooked smiles.

Neuroscientist Rachel Yehuda of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York had been keenly aware of the Holocaust since her childhood in a close-knit Jewish neighborhood in Cleveland. While her own parents were Israeli, she recognized in hindsight that the troubles of her friends’ European-born parents went far deeper than the normal dislocations immigrants feel. The descendants showed a greater sense of insecurity and instability, and focused on the potential for impending danger even when no danger was present. “Even in good times, some offspring seemed like they were waiting for the other shoe to drop,” she says.

Yehuda’s later studies revealed an intriguing distinction. These children not only were affected based on whether or not their parents had symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). She and colleagues also learned that offspring could be affected differently by parental Holocaust trauma based on whether it was the mother or father who was exposed. These differences were reflected in crucial changes in key brain circuits.

Her research is part of growing evidence that has yielded an entirely new understanding of molecular differences reflected in the brain between men and women, and how outside forces can permanently imprint neurological circuitry in sex-based ways. “There’s a complex interplay between hormones, experience and epigenetic changes in response to life events,” says neuroscientist Cheryl Sisk, who studies sex differences in the brain at Michigan State University in East Lansing.

Uncovering these differences in the hard wiring of the brain, researchers believe, can offer a better understanding of the biochemical origins of many physical diseases and psychological conditions that have few treatments. To be sure, there was a significant male bias in laboratory experiments on animals — neuroscience research skewed heavily toward the use of males, and five times more studies were conducted solely with male animals than with females or a mixture of the sexes. Scientists justified this because they believed there were no sex differences in brain function aside from reproduction.

But recent research has proved otherwise: There is a vast divergence in brain function across the gender divide. These newer studies are beginning to uncover the reasons why men are much more susceptible to neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and ALS; why autism, dyslexia, stuttering and early onset schizophrenia are three to four times more prevalent in boys; and why attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is diagnosed 10 times more often in boys. In contrast, women are diagnosed twice as frequently with depression, anxiety and panic disorders.

Drilling down to the source of these gender inequities could ultimately lead to better therapies. “While gender differences in cognitive function are small, the differences in vulnerability for diseases are spectacular,” says Geert J. de Vries, a neuroscientist at Georgia State University in Atlanta. “Nature has found a way of protecting one sex better than the other against certain diseases. This research might detect protective factors and give us insights in how to better treat these diseases.”

Remodeling the Circuitry

From the moment a fetus is bathed in steroidal hormones in the womb, the brain begins to take shape as male or female. “The gonads of the developing fetus are the epicenters of sex determination,” notes Margaret McCarthy, a neuroscientist at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. The SRY (sex-determining region Y) gene on the male’s Y chromosome orchestrates the formation of the testes, while the gonadal precursor will differentiate into an ovary by default (in the absence of the steroids produced by the testes). Other sexual characteristics depend on hormones secreted by the testes or ovaries later in embryonic development.

Yet the differentiation doesn’t end with gestation. Scientists now know that specific brain circuits underlying sexual differentiation can be remodeled through life. Hormones drive many of these sex differences, while major life events — such as puberty, pregnancy, parenthood or even traumas — also help shape male and female brain circuitry.

Studies like Yehuda’s provide a window into how this happens. Her initial research revealed that the children of Holocaust survivors were three times as likely to be diagnosed with PTSD, anxiety and depression, and engaged in more substance abuse than their peers. “Straight genetics did not explain the high prevalence of PTSD in this community,” says Yehuda. “Epigenetics provided a construct to conceptualize this — that experiences stay with us, particularly the traumatic ones.”

A micrograph shows isolated neurons from the brain of a human fetus. In infancy, about half the neurons will die during a pruning period. | Riccardo Cassiani-Ingoni/Science Source

Her more recent studies revealed marked differences in the way men and women coped with the horrors of the Holocaust. In 2014, her team compared 80 adults who had at least one parent who was in the camps with 15 demographically matched controls whose families did not face the same ordeals. Participants submitted blood and urine tests and were given a battery of psychological tests to evaluate their mental health and gauge whether the parents suffered from PTSD. The results showed that the children had a different stress hormone profile than their peers: They had lower levels of cortisol, the “fight or flight” hormone that helps regulate our response to extreme stress, and greater activity of an enzyme that breaks down cortisol — two differences that might make them more prone to anxiety disorders and PTSD.

What’s more, there was an increased sensitivity to cortisol if the mother, or mother and father, had PTSD. If only the father had PTSD, however, that sensitivity decreased. This was reflected in subtle DNA changes in an epigenetic gene that governs the stress response: Children whose fathers were survivors had greater genetic alterations in the GR-1 promoter, a tiny spigot that normally dampens genes that shut down the stress response. In other words, a more active GR-1 promoter caused a silencing of the gene, resulting in less cortisol. Having two stressed-out parents had the opposite effect, with the spigot leading to the release of more cortisol, making the children more fearful and anxious. This made sense, says Yehuda, “because volunteers generally described their fathers as being numb and detached, though prone to explosive outbursts, while mothers were riddled with anxieties.”

Meek Roosters

The study of gender differences in the brain and the resulting differences in behavior dates back to the mid-1800s, with the classic experiment of German physician Arnold Berthold, who showed that testicular secretions were essential for the normal expression of male actions. When he castrated a group of juvenile roosters, the fowl became puny and meek: They lost interest in the hens, they failed to sprout abundant plumage and were smaller than normal males. They didn’t crow or strut like their intact brethren.

But the truly modern era of behavioral endocrinology began in the late 1940s, when scientists such as endocrinologist Alfred Jost began studying how the release of steroidal hormones like estrogen and testosterone in the womb and during infancy created permanent sex differences. In the absence of testosterone, the embryo becomes female, and when male rabbit fetuses were deprived of testosterone — like Berthold’s castrated roosters — they became feminized.

Throughout our lives, these studies found, sex-specific hormones secreted by the ovaries or testes were responsible for instigating major life changes, such as the onset of puberty, having babies or fortifying parental bonds.

By the 1980s, the use of new imaging technologies like positron emission tomography (PET) provided unprecedented glimpses of a living human brain. More recently, techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have changed how we can study the brain and behavior. With fMRI, scientists get an even clearer picture of the differences because they can see which brain regions are activated while a person is thinking and processing information. “We’re on the threshold of a new awareness,” says Arthur Arnold, a neuroendocrinologist at UCLA who is a pioneer in the study of sex differences in the brain.

Diverging Developmental Milestones

Hormones regulate a lifelong reshaping of our neuronal pathways, programming a turnover and pruning of brain cells — a process that begins in the womb and continues to affect our intellectual, emotional and social development in adulthood. Studies in animals show that during a brief prenatal developmental window, testosterone and related hormones cause structural changes in the male’s brain so that it differs from that of a female’s. Researchers now think that in female animals, the presence of estrogen promotes female development at specific life stages, and having a second X chromosome makes female brains different from those of males.

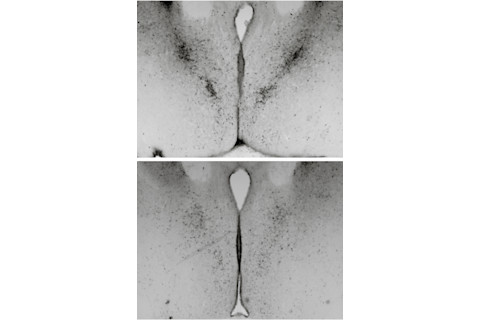

Images from a mouse study show the male brain (top) has many more cells in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, an area that regulates anxiety and response to stress. | Courtesy of Nancy Forger

Nancy Forger

Brain development involves an overproduction of neurons, followed by a period of trimming in which about half the neurons die during infancy. Studies in mice conducted by neuroscientist Nancy Forger of Georgia State University show that hormones act like chemical scalpels, sculpting the male brain differently from the female brain. As mammals gestate, testosterone and related hormones trigger cell death in some brain regions and spur cell development and more robust nerve connections between synapses in other regions, causing prominent sex differences in the brain and spinal cord. Forger’s research, for example, has shown that males have more cells in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, which regulates anxiety and response to stress, and in the spinal nucleus of the bulbocavernosus, which is made up of motor neurons in the spine that control muscles attached to the penis. Females, in contrast, have more cells in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus, which is a cluster of cells that help regulate the hormones that orchestrate ovulation.

“Men and women are more the same than different in the brain, but little differences can go a long way,” says Forger, who is also looking at the effects of epigenetic changes that cause differences in the brain that can last a lifetime.

Subtle changes in fetal steroid hormones may even predispose children to autism, according to a 2014 study by European researchers. They compared the concentrations of testosterone, cortisol and other hormones in the stored amniotic fluid samples of 128 Danish boys who have autism with 217 boys who do not. Tests revealed that during their fetal development, boys with autism were exposed to even higher levels of sex steroid hormones than the control group of boys. It’s a significant difference, and even a small rise in testosterone and other hormones may heighten risks for autism. In the womb, boys produce twice as much testosterone as girls, providing possible clues as to why autism strikes males in such disproportionate numbers.

The Imprint Experience

Sex differences become even more marked during puberty, when the brain undergoes another period of explosive growth. It kicks off when the hypothalamus — a tiny but powerful structure at the base of the brain — unleashes gonadotrophin-releasing hormone. This chemical signal sets off the chain reaction of physical changes that ultimately transform children into sexually mature adults. The biochemical onslaught of estrogen and testosterone sparks the development of the reproductive system and influences neurotransmitters like serotonin that regulate mood, which may help explain why teenagers can be reckless and excitable.

“We know puberty and adolescence is a major transition,” says Sisk, the Michigan State neuroscientist. “Kids go wacky for a long time due to their raging hormones and other factors. Now we’re trying to put all these pieces of the puzzle together to try and figure out what is going on.”

Research into how pubertal hormones influence the developing adolescent brain and how they shape adult social behaviors has direct implications for human mental health. That’s because a number of gender-based pathologies, such as eating disorders, depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, emerge during adolescence and contribute to teen suicide. This flux in hormones can also provide insights into the biological changes that prepare us to become a sexually mature adult, as well as the complex interplay between genetically programmed changes and those that are shaped by experience and the environment.

One study found that when paternal mice snuggled with their newborn pups in the nest, it prompted the formation of new brain cells that created a lasting connection with their offspring. | Orkemdemir/iStock

A recent Michigan State experiment shed light on which parts of the male brain sprout new neurons during puberty. In the 2013 study, researchers injected adolescent male hamsters with a special chemical marker to detect the growth of new cells. When the hamsters matured into adults, they were allowed to mingle and even mate with the females. Immediately after these interactions, scientists examined the brains and discovered the new cells that formed during puberty had been integrated into the amygdala, an almond-shaped region deep inside the brain that is thought to play a role in such social behaviors as mating. The new research suggests this nerve growth is important for adult reproduction because it may have created neural pathways that enabled the males to interact with females.

“We know that experience is at least as powerful a regulator and shaper of brain structure and function as hormones, and boys and girls have very different experiences,” says Sisk, who was involved in the study. “The brain metamorphosis of puberty … is not just about the fine tuning of synapses or making more of a particular neurotransmitter. It’s really a complete makeover that includes the addition of brand-new cells in places we never considered before to give us the tools we need to navigate our way through the human social fabric as adults.” The turmoil of the teenage years also can drive hormonal changes that permanently alter neural pathways for emotional regulation. How each sex handles these stresses provides clues into the biological roots of gender differences in incidences of mental illnesses, and illuminates why women have higher levels of anxiety and depression. In 1989, University of Wisconsin researchers launched a longitudinal study, called the Wisconsin Study of Families and Work, which collected medical and demographic data on several hundred children from birth to early adulthood. In a 2002 study that followed 174 of these kids, researchers reported that 4-year-olds living in stressful environments — their mothers were depressed, their parents fought, or there were financial difficulties — had high levels of the stress hormone cortisol in their saliva. When the children were observed two years later, those with more cortisol exhibited greater behavioral problems, such as aggression and impulsivity.

The researchers checked back in with the study subjects when they turned 18 to find out how the increased cortisol affected their brain function. Researchers scanned the brain connections of 57 participants — 28 females and 29 males — using fMRI. Brains of teenage girls exposed to high levels of family stress when they were toddlers showed reduced connections between the amygdala, which is also known for processing fear and emotions, and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, an outer region responsible for emotional regulation. This correlated with anxiety in adolescence: Girls with higher scores on anxiety tests have weaker synchrony between these two regions. Yet the young men in the study didn’t exhibit any of these neural patterns, suggesting that this may be a developmental pathway that makes females more prone to becoming anxious. “Males are better at avoiding depression,” says Georgia State’s de Vries, “and experiments like these may illuminate their protective factors.”

Parenting Rewires the Brain

As we move into adulthood, parenting also generates brain changes along sex-related lines. Expectant mothers spend nine months marinating in a flood of hormones that alter their brain circuitry. Once they give birth, hormones are released to stimulate lactation and to cement an emotional bond with their newborns. Preparing for parenting rewires fathers’ brains as well, but in a different way. For mothers, that hormone surge is part of an exquisitely choreographed internal program that nurtures developing fetuses throughout pregnancy. For fathers, the social interaction with their offspring spawns binding neural ties.

One study found that when paternal mice snuggled with their newborn pups in the nest, it prompted the formation of new brain cells that created a lasting connection with their offspring. Samuel Weiss, director of the Hotchkiss Brain Institute at the University of Calgary, and his colleagues reported that nerve cells sprouted in the olfactory bulb, the seat of the sense of smell, and in the hippocampus, the brain’s memory bank. These particular brain cells are also regulated by prolactin, a hormone that orchestrates the milk production in the breasts of new mothers. In the fathers, a surge of prolactin helped the neurons form a permanent circuit in the brain, which integrated a pup’s scent into the father’s long-term memory. As a consequence, even when the fathers were separated from their babies for a few weeks — normally enough time to forget cage mates — they easily recognized their pups when they were reunited. But new neurons formed only if the father had physical contact in the nest with the pups.

“The nuzzling stimulates the production of the hormone prolactin,” says Weiss. “If you block prolactin, it stops brain cell production, and memories aren’t formed because no nerve cells are produced. But this has long-term implications for mental health because these social interactions yield the release of hormones that change the brain, which, in turn, forms social memories. And these memories reinforce positive social interactions, creating positive feedback loops.”

On the epigenetic side of the equation, research into different parenting behaviors indicates that positive experiences may become embedded in our DNA — and in a way that also breaks down along gender lines. While Yehuda’s research on the children of Holocaust survivors suggests we can’t escape the legacy of trauma experienced by our parents, the opposite may be true, too: Healthy parenting can have a salutary effect on not only their offspring but also future generations.

Weiss’ group looked at how different parenting models affected new nerve growth in the brain, and the behavioral impact of the neurological changes. They used 8-week-old mice and placed them into three distinct environments. In the first group, mothers raised their litters alone until their pups were weaned; in the second, the impregnated females were put in cages with virgin females who helped them rear the young mice; and the third group consisted of pups reared by both parents. When the young animals were successfully weaned, researchers gave them a series of tests to gauge their fear response, along with their cognitive, memory and social skills. The mice were also injected with a dye that could illuminate the footprints of new nerve cell growth in the brain.

Perhaps not surprisingly, two parents were better than just one, although it didn’t matter whether it was a combination of mom and dad or the two females. The extra attention the offspring received in the enriched environments — nursing, licking and grooming — translated to denser nerve growth in the dentate gyrus, which is in the hippocampus, the brain’s memory warehouse believed responsible for learning and storing short-term memories.

But while male pups raised by two parents produced more gray matter in the memory-processing regions, dual-parented females sprouted twice the number of nerve cells in the corpus callosum, a thick bundle of nerve fibers that enhances communications between both sides of the brain and facilitates spatial coordination and sociability.

In fact, female mice raised by two parents were more proficient at negotiating a ladder with uneven rungs than females with just one parent — and all females were far more adept at this task than the males, even those reared by two parents. These effects endured not only throughout the animals’ lives but were carried on to the next generation and along the same gender lines: The offspring of dual-parented pups turned in superior performances on tests of cognitive ability and social skills than mice raised by single parents.

“We already know that in humans, positive early experiences lead to stronger adults that have less problems coping and managing life’s challenges, but the generational results are mind-numbing — who would imagine that if you have a positive early experience that your offspring would benefit?” says Weiss. “We’re not that far away from the point where we will be able to explore similar things in humans.”