Dr. Jeffrey Schwartz got a phone call at 3 p.m., a script before 5 p.m. and the next afternoon he was there, sitting with Leonardo DiCaprio, exploring the intricacies of one of the most debilitating mental illnesses in medicine.

DiCaprio was tackling the role of Howard Hughes in The Aviator, a part requiring him to arc — as Hughes did — from genius billionaire to shaggy recluse, caught in the grip of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Schwartz’s books, Brain Lock and The Mind and the Brain, had established him as one of the world’s foremost authorities on the underlying mechanisms and treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, a condition that plagues sufferers with unreasonable thoughts and fears, which in turn compel repetitive behavior.

He would not teach DiCaprio the mannerisms of people with OCD, Schwartz announced on day one. Instead, he would show him “how to become a person with OCD,” so his brain was “like the brain of a person who has the disease.”

The message was ominous, but DiCaprio proved game to try. He quickly pointed Schwartz to a particular segment of the script. “Right here, for three pages, I only have one line,” he said. Show me the blueprints, repeated 46 times, with minor variations.

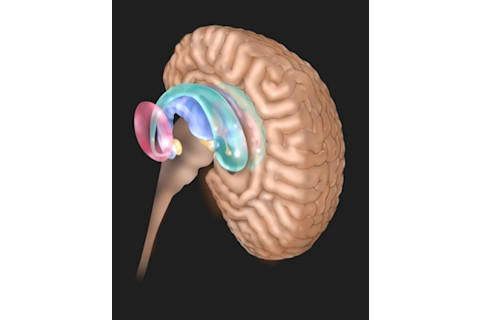

Schwartz explained that people afflicted with OCD engage in a wide variety of problematic behaviors — compulsive hand washing, door opening, repetitive checking of ovens and doors, even repeating the same word, phrase or sentence. The cause, at a neurological level, is hyperconnectivity between two brain regions, the orbitofrontal cortex and the caudate nucleus, creating a tidal wave of unfounded mortal fear and triggering habitual response as the only way to attain calm. But the worst part is that, despite recognition that all these thoughts and behaviors are irrational, the OCD sufferer feels driven to obey them, nonetheless.

Schwartz walked DiCaprio through the underlying neurology to help him understand that, for Hughes, those four words — show me the blueprints — held a magical power, offering him an escape from his fear. “Those words, he’s repeating them like his life depends on them,” Schwartz advised. “But he also understands that this doesn’t make any sense.”

In the 2004 film that eventually emerged, this scene is perhaps the most painful to watch. DiCaprio, as Hughes, twists the sentence in new directions with each rephrasing, emphasizing different words and employing different cadences. Sometimes he races through the sentence almost under his breath. Other times, he slows down, seeking the right combination of sounds, the right rhythm, to free himself from the fear roiling in his gut. All the while, his face betrays a tortured self-revulsion.

DiCaprio left The Aviator with an Oscar-nominated performance and perhaps a mild case of the disease. It reportedly took him about a year to get back to normal. And today, his willful descent into the illness and subsequent recovery represents one of the most dramatic public examples in our popular culture of neuroplasticity — the ability of the brain to change in shape, function, configuration or size.

But Schwartz says mainstream science has yet to come to grips with an experience like DiCaprio’s, based on what Schwartz calls “self-directed neuroplasticity,” the ability to rewire your brain with your thoughts. This kind of power doesn’t only rescue his patients, he says. It rescues free will.

The notion that we have free will flies in the face of much modern neuroscientific research, which suggests an ever-increasing number of our “choices” are somehow hardwired into us — from which candidate we vote for to which flavor of ice cream tops our cone. In fact, neuroscientists like David Eagleman and Sam Harris have released best-selling books offering that we are, at bottom, high-functioning, delusional robots.

And so, at a time when free will is on the run, few of our culture’s most prominent thinkers agree with Jeffrey Schwartz — a scientist, as it happens, who is entirely comfortable with being disagreeable.

OCD Family

On a warm, fall evening, Schwartz leads me to the campus at the University of California in Los Angeles to witness an OCD group therapy session. Short and squarely built with tight, curly hair and the stooped shoulders of an aged wrestler, Schwartz ambles through the parking lot until he spots one of his patients and calls out to him, warmly, by name.

“How you doing?” he says.

The man, smoking a cigarette and leaning against a brick wall just outside the entrance to Schwartz’s building, waves and indicates with a hand gesture, pointing inside, that he’ll talk in the group session. Schwartz nods, turning to me as we pass him. “Uh-oh,” he says. “Maybe things aren’t going so well for him.”

Schwartz takes the last couple of strides ahead of me and opens the door to the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, a three-story glass and brick collection of classrooms and labs. “Well,” he says, cocking an eyebrow at me. “Here we go. These are my people.”

Walking into a room filled with Schwartz’s patients is like walking in on a band of revolutionaries. They have that easy air of familiarity and quiet sense of accomplishment. They greet Schwartz, their leader, warmly. People speak of regaining time previously lost to their compulsions. One man, an actor, says he feels confident enough to audition for parts again.

Paula Scott, the senior client among them, captures just how dramatic their trip has been. “When I first met Jeffrey,” Paula says, “I was thinking about killing myself. Now, I am not even struggling with my OCD.” Paula’s illness is still present, but the condition no longer torments her, no longer controls her. OCD is just something she handles as she goes about her day.

All is Suffering

The insights underlying Schwartz’s groundbreaking techniques can be traced back to his youth. The Holocaust had ravaged his bloodline, a heavy legacy about which an elder relative educated him. “I remember he told me that it was my job to live for these people who had died,” says Schwartz, “and he didn’t mean that as some sort of metaphor, or to inspire me. He meant it literally.”

While other kids his age played, he spent long hours in the library, reading through Holocaust trial transcripts. On page after page, he read testimony about people who performed horrifying acts for the sake of power, money or simply to get along in a country suddenly steeped in the wicked. He emerged, he says, with an image “of humanity as being fallen and in need of some kind of help.”

His college years, spent at the University of Rochester, yielded another influence: the focusing power of mindfulness, a Buddhist practice in which adherents learn to view their own thoughts and impulses with complete impartiality. Aided by mindfulness, Schwartz did so well in school he was accepted as an honors scholar in philosophy in Edinburgh, Scotland.

When he embarked on his career in medicine, he knew he wanted, somehow, to combine all these elements: He wanted to demonstrate that the Buddhist practice of mindfulness could help us choose something other than holocausts and heal our fallen humankind.

Schwartz got the chance in 1983, when he agreed to work with UCLA neuropsychiatrist Lewis Baxter to tease out the mechanism of OCD. The Baxter team would be using the then-new positron emission tomography (PET) scanner, a hulking imaging machine Schwartz remembers “looking like something out of 2001: A Space Odyssey.”

To conduct a PET scan, technicians injected patients with a biologically active tracer particle made partly of positrons (positively charged electrons) and attached to some other molecule with a role in metabolism, like water or glucose. By tracking the positrons emitted as the tracer breaks down, the machine can capture images of biological processes. In this case, Schwartz and Baxter aimed to follow blood flow in the brain.

While the team worked, Schwartz scoured the literature for insight and found a largely overlooked study by neuroscientist Edmund Rolls. Rolls used monkeys to investigate the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), an area of the brain associated with decision-making. The brains of the monkeys were imaged as they grew comfortable licking a bar in order to obtain a sweet liquid. Then they were imaged licking the same bar after the liquid was replaced with a salty brine.

Rolls found activity in the OFC spiked when the monkeys were surprised by the new liquid. It was an ingenious study, Schwartz thought. Rolls had revealed the OFC to act as an error detection circuit. It made sense then to look at the OFC in relation to OCD, which fills patients with mortal fear that something is wrong.

Around the same time, Schwartz suggested the team investigate the caudate nucleus, a tail-shaped structure near the OFC that serves as the habit center of the brain. The caudate nucleus, he thought, might act as a kind of nexus for OCD — a traffic hub where rational thinking in the cerebral cortex meets the more primitive, emotion-ruled centers of the brain’s limbic system. It would be a natural ground zero for the noxious brew of repetition and terror to collide.

The research took many months. But one day Baxter took Schwartz aside to say, “We’ve got it.”

The data were clear. OCD subjects, as opposed to healthy controls, demonstrated significant hyperactivity in the OFC and caudate — even at rest. The images turned up in PET scans as bursts of color, rendering these brain regions as small fires, perpetually burning and, clearly, altering the functioning of the brain even when no episode was underway.

Free Will Therapy

Now that the neural circuitry of OCD was identified, researchers could test therapies. Using imaging technologies like PET, they could see if a given treatment tempered the fire in the brain.

For Schwartz, this was the chance to invoke his interest in mindfulness. He imagined a woman caught in the grips of ceaselessly washing her hands, yet aware her hands weren’t dirty. Able to reflect on the bizarreness of her thoughts and her behavior, she continues to wash only because it seems like the only way to ease her fear that she is contaminated.

In this sense, OCD reflects a key aspect of mindfulness meditation — granting the patient a detached perspective from his or her own thoughts. Schwartz speculated that this awareness could enable a mindfulness-based treatment strategy. After all, if the point of mindfulness is to stand back dispassionately from all our ideas and impulses, couldn’t an OCD patient use mindfulness to step back even from mortal fears and compulsions? Perhaps mindfulness could help rewire the OCD circuit in the brain.

Schwartz met one of his earliest patients, Paula Scott, in 1987, when she was deep in the throes of a case of OCD so surreal and severe she regularly contemplated suicide. Paula’s illness manifested as the irrational fear that her boyfriend was an alcoholic and drug addict.

Schwartz thought Paula’s case was particularly compelling because the repetitive behavior she chose to alleviate her fear demonstrated just how aware she really was. She knew, for instance, that if she constantly peppered her boyfriend with questions about drug and alcohol use, he’d realize something was off. “I had to find a way to conceal my feelings from him,” she says, “while still giving in to the compulsion.”

Her solution: question him rigorously without tipping him off to her particular fear. She asked him multiple questions about his day, essentially asking him to walk her through what he ate for breakfast, when he got to work, what he did that morning, and with whom he ate lunch, seeing if he might slip and say something that hinted at drug addiction.

Others joined Paula in Schwartz’s therapy group. They spoke of rubbing their hands raw to avoid contaminating themselves and, by extension, their loved ones. They talked of being late for work because they spent so much time checking the oven and the door locks. And each week, Schwartz urged his patients to experience their OCD symptoms the way a mindfulness practitioner, in meditation, strives to experience every thought — dispassionately, without succumbing to emotion.

After Schwartz’s OCD patients mastered mindfulness, their symptoms subsided, and the fire in their brains’ orbitofrontal cortex and caudate nucleus (shown here in green) dimmed. Jim Dowdalls/Science Source

“It’s not me! It’s my OCD!”

In these earliest days, Schwartz didn’t really know where he was going, only his starting point. And what he asked of his clients was truly dramatic: He asked them to recognize an OCD-related thought as soon as possible and relabel it as unreal — merely a symptom of their OCD — without giving in to it. The group responded enthusiastically, but things took off after an older woman in the group, Dottie, suddenly exclaimed: “It’s not me! It’s my OCD!”

This became a rallying cry for the group. And Schwartz realized he’d found his first step, relabeling.

If a patient suffered from a constant obsession with dirty hands and a compulsion to wash them, Schwartz advised the patient to think: This is not an urge to wash my hands. This is a bothersome thought brought about by my OCD. As soon as he hit on this method, his patients came back the next week and reported improvement, claiming they no longer felt the disease controlled them.

Yet they were still symptomatic, and the symptoms interfered with their lives. Weeks in, as his patient group reported for another session, one of them asked, “Doc, can you just tell me why the damn thing keeps bothering me — why it doesn’t go away?” Schwartz happened to be carrying around some brain scans of OCD patients in a folder. “You want to know why it doesn’t go away?” Schwartz said. “I’ll show you why.”

Retrieving the scans with a flourish, he pointed to the OCD circuit he’d worked with Baxter to establish. “This region of the brain is hugely overactive,” he said, and then Pop! He saw a change in his patient’s face and the excitement in everyone listening. Paula was one of the patients who experienced this eureka moment and felt liberated. These strange thoughts about her boyfriend’s drug addiction were no longer a sign of insanity. They were no longer even a product of her self. They were just the faulty transmissions of a malfunctioning brain.

Schwartz felt the energy in the room rise, and he saw the previously defeated men and women of his OCD group rally and strengthen as surely as if they had just inexplicably gained more muscle tone. This became the second step: reattribute. He was teaching his patients to reattribute their OCD symptoms to some gnarled brain wiring, teaching them to see the functioning of their brain as meaningfully separate from their sense of self.

Over the following weeks, patients started to report victories regularly. At first these wins were small. Paula could hold off on questioning her boyfriend about his day for longer periods — first minutes, then an hour or more. She could get by while asking fewer questions. But as time passed, the patients reported something more remarkable: The intrusive thoughts of OCD were diminishing, occurring less frequently, and coming on with less power.

Schwartz believed that this was because his patients were in fact using the power of their minds to rewire their adult brains — a finding at odds with the view in those days that only children’s brains could go through such enormous change.

One evening, while out of the office, Schwartz realized his patients needed more to do, something to focus on besides the intrusive thoughts of OCD. He thought back over the practice of mindfulness and found an analogy he liked. In meditation, if he became emotionally invested in a particular train of thought, he sought to refocus himself by drawing his attention back to his breathing.

Using that same concept, he gave his patients license to replace monitoring their breath with whatever behavior they found most compelling. Some patients found it helpful to turn back to the same healthy behavior each time an OCD episode struck: going for a walk, perhaps, or gardening.

Schwartz had found three steps — relabel, reattribute and, now, refocus.

But he needed a final step, something to pull them all together. He called that step revaluing. The OCD thoughts that patients once considered so important were to be systematically deconstructed, understood and finally revalued as, in Schwartz’s words, “trash … not worth the gray matter they rode in on.” Conversely, Schwartz’s patients learned to value their alternative behavior highly.

Schwartz’s four steps worked, but it wasn’t easy. It took, and these words struck Schwartz as key, a tremendous force of will.

The Rewired Brain

Eventually Schwartz began to feel he was seeing free will in action: the people under his care choosing, again and again, to engage in a new behavior. But he needed to wait and see if that evidence would turn up in a brain scan. And after 10 weeks of treatment in the four steps, it was time.

His patients, their brains imaged before any treatment began, entered the hulking scanners a second time. Baxter crunched the data and told him the news: The amount of activity in these patients’ OCD circuits had decreased to a degree commensurate with the best results achieved by pharmaceutical therapy. The OCD circuit, so brightly lit in the baseline scans of his OCD sufferers, now glowed more softly.

Schwartz published his findings in 1992 and replicated them in 1996, adding nuance to our notion of adult neuroplasticity. But the ensuing years, have brought a host of theorists and tracts undermining free will — and the modus operandi of Schwartz’s therapy for OCD.

Neuroscientists Sam Harris and David Eagleman published books on the topic in the past couple of years, both of which made best-seller lists. Harris is unequivocal, referring to humankind as “biochemical puppets.” In his view, we can choose our path in life no more than the eight ball can choose whether or not to fall into the corner pocket.

In his book, Eagleman is less certain that free will doesn’t exist in some form, but ponders what this current vision of mind and brain means for crime and punishment: If we really don’t choose our actions, how can we blame criminals for the havoc and pain they cause?

Schwartz refers to all these arguments as “unhealthy” and “damaging,” especially to the dignity of his OCD patients and the hard work they put in to reclaim the hours and minutes of their lives. “They describe a struggle,” he says of his clients. “They sit there, sweating, shifting their attention away from the compulsion and toward some healthy new behavior.”

His influence might aid them for a short time, he allows, but his patients go home for a week or two to fight OCD on their own. In a purely neurological sense, if determinism held sway, his patients have no free will and no hope. The scans themselves, he says, suggest free will is alive and well.

Schwartz believes free will is so powerful it literally influences our evolution. In 2004 he even added his signature to The Discovery Institute’s “Scientific Dissent From Darwinism,” which supports the heretical concept of intelligent design. While Schwartz believes in evolution, he says that the mechanism of neuroplasticity, which changes the shape of our brains, has likely shaped human evolution, too. In his contentious style, he had made his views clear.

Nothing to Hide

My visit is almost over, and on Sunday Jeffrey Schwartz takes me with him to church. “This is who I am. I have nothing to hide,” says the Jew turned Buddhist turned Christian. As the church band unwinds one tune after another, it is a surprise to hear Jeffrey Schwartz — a man who spends so much time arguing — raise his voice for some other purpose: to sing. Schwartz’s instrument is imperfect, maintaining only an intermittent connection to the proper key, but it is strong and surprisingly smooth.

As the band performs the final song of the service, a gently rocking treatment of “How Great Thou Art,” Schwartz hits the crescendo at a volume that suggests his depth of conviction, his voice keening out over the rest of the people nearby.

The music ends, then, and Schwartz breaks into a buoyant grin, transformed into a portrait of something unexpected: a man at peace with his choices.

[This article originally appeared in print as "In Defense of Free Will."]

Read an extended version of this story in Discover’s exclusive e-single Obsessed: The Compulsions and Creations of Dr. Jeffrey Schwartz.