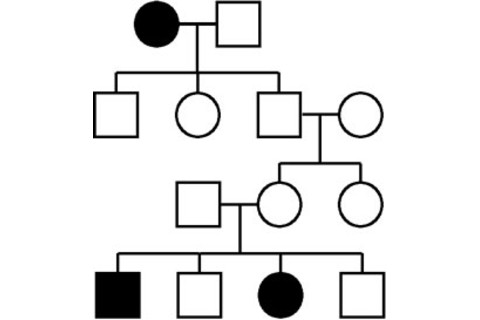

After yesterday's post I feel it is important again to reiterate that there is an unfortunate tyranny of the gene-as-physical-entity when it comes to our understanding of human heredity. To clarify what I mean, I think it is useful to borrow a framework from Andrew Brown. On the one hand you have a conventional modern mainstream understanding of the gene as a molecular biological entity, fundamentally derived from DNA and its role as envisaged by Francis Crick and James Watson, but with roots deeper back into the physiological genetic tradition which Sewall Wright was embedded within. In contrast to this concrete and biophysical conception of the gene there are those who conceive of the gene as an abstract unity of analysis. Richard Dawkins is the primary proponent of this viewpoint on the public intellectual scene, though men such as William D. Hamilton self-consciously understood the difference between their own genetics, and that which arose out of the insights of Crick and Watson. The key point which you have to remember is that the gene was conceived of before its substrate, DNA, was understood. Genes, and therefore genetics, predates molecular biology. For example, when you look at the pedigree above you see an autosomal recessive trait (dark). This is inferred by the pattern of inheritance. It is not adduced from a feature of molecular biology. If it is an autosomal recessive trait with a locus of high penetrance, then no doubt there is a clear molecular biological grounding for how the consequent phenotype manifests. But an understanding of molecular biology is not necessary to infer the genetic character of the trait. More colloquially: you don't need to know the exact gene of major effect to conclude that a trait is genetic.

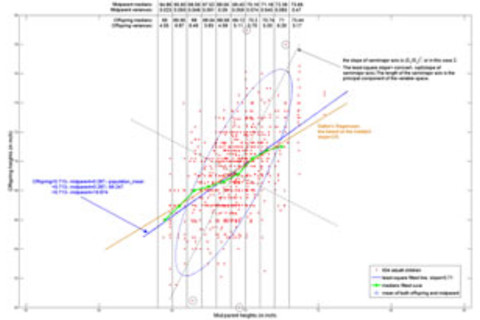

And the tyranny of the gene is even more pernicious when it comes to a concept which predates genetics itself, but is clearly ultimately inextricably tied to a genetic understanding of the inheritance of traits: heritability. Heritability is simply the proportion of variation in the trait that is due to variation in the genes. One infers it in a classical sense by tracing correlations of the trait of interest across relatives of differing degrees of relatedness. Fundamentally it is a "gene blind" summary of statistical patterns and associations. Why does all this matter? Because today people want a specific gene, elucidated by contemporary molecular biological methods, before they accept that a trait is "genetic" or "heritable." This is the fundamental tragedy of behavior genomics. It is clear that many behavioral and cognitive traits have a heritable component, but the public is always hungry for the "X gene."