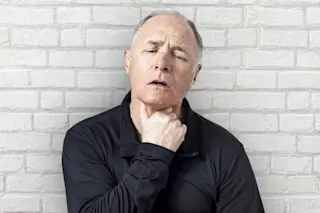

Richard came to my clinic with a common complaint: difficulty swallowing food.

At first, he had trouble only with large bites. But now, even small bites and drinks were causing him problems. The 70-year-old attorney often felt like he was choking.

For most of his life, Richard exercised regularly and was fit, but over the past year, he had lost weight and energy. “Maybe I’m just getting older,” he told me, “but I feel like I am having a lot more troubles than I used to.”

Having problems swallowing is common. The act requires a complex coordination between the mouth, tongue and esophagus. Various muscles need to work in the right way at the right time to allow food to go from your dinner table to your stomach and not get stuck midway or inhaled into a lung.

The medical term for difficulty swallowing is dysphagia. Some people have trouble ...