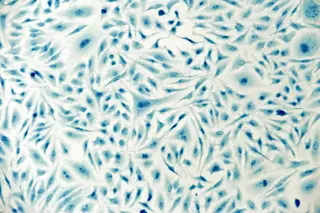

For three days, Alex Jofriet drank one 8-ounce glass of milk per day. This was a big deal because he hadn’t touched the stuff in years. Jofriet has Crohn’s disease, a poorly understood chronic inflammation of the intestine. Eat the wrong thing, or even too much of the right thing, and he would pay the price: hours in the bathroom wracked with stomach pain, gas and diarrhea.

But Jofriet took the risk. He and his doctor, Shehzad Saeed, decided to set up an experiment, and Jofriet would be the only subject. For those three days, he would drink milk like he wasn’t afraid, like he hadn’t spent the past eight years negotiating a careful truce with his digestive system. He would drink milk and record how he felt on those days. How many bowel movements did he have? Was there blood in his stool? Did he have stomach pain and ...