It’s Thursday morning at the Portland Public Schools central kitchen on Riverside Street in Portland, Maine. A crew of white-coat-clad kitchen employees is preparing locally landed Acadian redfish fillets topped with oyster cracker crumbs and seasoned with Old Bay for more than 2,000 elementary school students. This facility prepares local seafood once a month as part of the district’s commitment to the local food movement.

“We’re either doing redfish,” says Ron Adams, the director of food services, “or sometimes, we’ll get the haddock coming off Georges Bank.” Although Adams prefers the haddock, he’s pleased with the redfish, especially since it helps support beleaguered local fishermen.

Species like Acadian redfish, scup and sea robin have earned the moniker “trash fish” in commercial fishermen’s eyes because demand is so low that the price per pound makes them hardly worth landing. Some of these species are so abundant that they can interfere with harvesting money-making species, such as cod. But cod and other iconic New England seafood species are disappearing because of overfishing, and fisheries managers have drastically limited the amounts fishermen can catch. So trash fish are now getting a makeover.

Numerous campaigns by environmental groups are looking to rebrand trash fish. But some New England politicians think the process is too slow — and the markets too small — to provide the immediate assistance fishermen need. In the past year, some politicians have begun looking to federal food programs as customers for one of the most abundant and despised species: the Atlantic spiny dogfish. But proponents of serving dogfish in school lunchrooms, food kitchens, prisons and disaster shelters seem to have missed the simple fact that the mercury levels in the fish mean that serving it to these populations could be a risky move.

Cussed Dogfish

New England fishermen have hated dogfish for a long time, and there has never been a significant domestic market for the species. New York Times articles penned more than a century ago bemoan the dogfish as “cussed,” “ferocious” and so thick “it’s good-bye fishin'.” In the mid-20th century, dogfish gained some goodwill as European demand drove up New England exports. Since the 1950s, the dogfish has been the default choice for fish and chips across the United Kingdom, where it’s commonly called “rock salmon.” In Germany and France, the fish is sold as “small salmon” or “sea eel.” Dogfish fins have found a home in Japanese-Chinese cuisine.

A dogfish swimming. (Credit: Boris Pamikov / Shutterstock)

Boris Pamikov / Shutterstock

Today, the dogfish population in the western North Atlantic is as large as fishermen can remember. The Marine Stewardship Council recently certified the population as a sustainable fishery. Unfortunately, as dogfish numbers have boomed in recent years, international markets have slumped, owing to a rebounding Northeast Atlantic cod fishery and changing tastes.

New England now finds itself with a glut of dogfish and few willing buyers, and at the same time, catch limits on other species are being drastically tightened. It’s estimated there are 23 times as many dogfish as cod in the Gulf of Maine right now, but dogfish earn only a fraction of cod’s price. To make matters worse, dogfish both compete with cod for food and directly prey on cod.

Solving the Surplus

In that quandary, fishing industry advocates and lawmakers see an opportunity for government intervention. Last spring, 19 members of Congress from the Northeast wrote to the U.S. Department of Agriculture asking the agency to buy Atlantic spiny dogfish under the Section 32 program, which buys surplus food and then makes it available to the National School Lunch Program and other federal programs. In addition to providing affordable food, the aim of Section 32 is to help absorb the excess supply of certain foods and thereby shore up prices.

A USDA commodity purchase would, the lawmakers argued, be a win-win: cheap food for institutions and a much-needed “bridge” for struggling Northeastern fishermen, to tide them over until cod populations could recover. The USDA is evaluating the request. If it gets approved, dogfish filets, nuggets and tacos would make their way to government programs across the country.

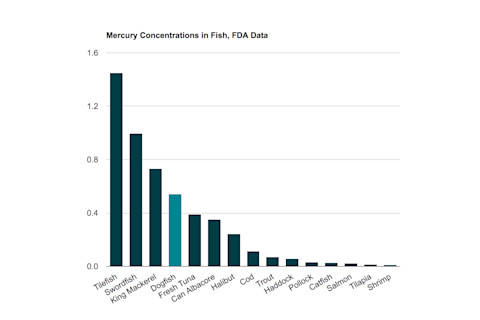

But while New England lawmakers have been advocating more dogfish consumption, some of their states’ own departments of health have been advising against it. That’s because the dogfish, a type of shark, sits high in the ocean food chain and therefore accumulates mercury from the smaller fish it eats. Maine, for instance, advises pregnant and nursing women, women who may get pregnant and children younger than 8 to avoid dogfish. The rest of the population should eat no more than two dogfish meals per month, the advice says. Federal guidelines don’t mention dogfish specifically, but the first of only three recommendations in the current FDA-EPA advice for women of reproductive age and young children is, “Do not eat shark, swordfish, king mackerel or tilefish.”

Dozens of studies show that elevated mercury in the body is associated with adverse health effects, especially in vulnerable populations such as children. In young children and fetuses, studies have shown even relatively small doses of mercury can be linked to damage to the developing brain. According to the WHO [pdf], methylmercury – the type of mercury found in fish – can cause mental retardation, seizures, vision and hearing loss, delayed development, language disorders and memory loss in children. In adults, elevated blood mercury levels are associated with impaired brain function [pdf], and acute mercury poisoning has been documented in people who consumed substantial amounts of high-mercury seafood in a short period of time.

“Even a ‘low-mercury’ variety of shark,” says Edward Groth, a former senior scientist at the Consumers Union and an independent scientist who consults for the Mercury Policy Project (MPP), “is still a very high-mercury fish.”

Measuring Mercury

There’s little data on mercury levels in dogfish specifically, but the data that does exist seems to indicate that officials need to proceed with caution.

The FDA Monitoring Program data set, which includes only 19 spiny dogfish specimens, puts the average mercury concentration in dogfish over 0.5 parts per million – high enough to result in an advisory for women of reproductive age and children in many states. That’s some 50 times higher than many low-mercury types of seafood such as clams, shrimp and tilapia.

It’s higher, too, than the average mercury levels in canned albacore (white) tuna in the same data set. Tuna is a useful comparison since it’s called out specifically in the FDA-EPA advice. The guidelines advise women who might become pregnant, women who are pregnant, nursing mothers and young children to eat no more than about one can of albacore tuna per week. What’s more, the advice is out of step with the agencies’ own underlying science, which shows that even one serving of albacore tuna per week may put individuals at risk. (See "Interpreting Reference Doses" below.) So even if dogfish poses no more risk than canned albacore, it is, at the very least, a species of concern for a food being considered for the National School Lunch Program.

Other studies place mercury levels in spiny dogfish somewhere between canned albacore tuna on the low end and Spanish mackerel, swordfish, bluefish and orange roughy on the high end. Several studies have found individual dogfish specimens with mercury concentrations exceeding the FDA action level for mercury in seafood – the level at which the FDA would consider removing the product from the market. At least one study found spiny dogfish had a mean mercury concentration twice that of canned albacore tuna.

Filling In the Gaps

You can see Narragansett Bay from marine biologist David Taylor’s office at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island. On his walls are framed scientific illustrations of fish, and a rack of well-appointed fishing rods stands in front of academic books and journals dealing with fisheries ecology, habitat restoration and environmental toxicology. Here in the Ocean State, Taylor says, “it seems like everyone fishes – and the majority eat what they catch.”

David Taylor stands in his office at Roger Williams University. (Credit: David Silverman for Roger Williams University0

David Silverman for Roger Williams University0

Taylor’s research focuses on mercury contamination in fish caught and eaten by Rhode Island’s recreational anglers. When Taylor started his work, there was a lot of research on mercury levels in freshwater fish and in some well-known commercial saltwater species, like swordfish and tuna. But there was surprisingly little research on mercury contamination in commonly consumed saltwater species such as striped bass, tautog, bluefish and summer and winter flounder.

In 2009 he began investigating dogfish. He wasn’t motivated, at first, by health concerns. Dogfish has never been a popular food choice among American anglers; if not handled properly, the flesh has a foul taste because dogfish essentially urinate into their own flesh.

Rather, Taylor turned to dogfish to better understand how mercury moves through ocean food webs. He found that the existing data on mercury concentrations in dogfish in the Northwest Atlantic were, at best, sparse. He was going to need to start collecting.

Since then, Taylor has collected and archived almost 300 dogfish samples, probably the most robust data set for mercury levels in dogfish in the Northwest Atlantic to date. His data, which will appear in a forthcoming article in Marine Environmental Research, suggest that species of dogfish, as well as age and size, can have a significant effect on mercury concentrations. In the Atlantic spiny dogfish he tested, Taylor says he found mercury levels “exceeding the EPA action level for mercury in seafood” (0.30 ppm) in more than 50 percent of market-size samples. For the closely related smooth dogfish, that figure was 90 percent – a relevant statistic since sometimes different dogfish species are caught and sold generically as dogfish in areas where the species’s ranges overlap.

According to Taylor, even a liberal reading of his data would likely place dogfish in a category where, based on joint FDA-EPA advice, he would recommend no more than a single serving of dogfish per month for men. Women of childbearing age and children would be advised to forgo dogfish altogether.

Interpreting Reference Doses

Although there is no “safe” threshold for mercury in seafood, looking at the relative concentrations of mercury puts the risks associated with dogfish into perspective.

Health officials use a tool called a reference dose (RfD) to quantify risks from toxins in food. It is a maximum acceptable daily oral dose of a toxic substance like mercury. The RfD set by the EPA for methylmercury (the organic form of mercury most common in seafood) is 0.0001 mg/kg/day. Using this reference dose, a 154-pound individual eating 0.175 kg (about one 6-ounce serving) of seafood per week should limit consumption to a fish species with an average mercury concentration of less than 0.28 ppm for that meal. This means that, using the FDA’s mercury data, one meal of canned albacore tuna (at 0.35 ppm) per week could put that individual just above the RfD for methylmercury.

The same individual could, however, consume multiple meals of lower-mercury seafood within the same time frame without coming anywhere near the RfD. For example, eating one serving of salmon (at 0.02 ppm) every day would still not reach the RfD. Based on independent researchers’ data, average mercury concentrations in spiny dogfish are somewhere between 0.35 ppm and 0.80 ppm. The FDA’s data place the mercury concentration in dogfish above 0.50.

Truth in Labeling

A final factor worth considering in the proposed federal purchase of dogfish is labeling. Parents looking over the school lunch menu, pregnant inmates or families eating at food kitchens may have heard that they should limit their consumption of canned tuna, and it will be fairly obvious what foods contain it. Dogfish, on the other hand, would likely be served as generic breaded fish fillets, fish sticks or fish tacos, possibly mixed in with other white fishes. In petitioning the USDA, industry leaders advocated just such an approach, saying, “Breaded dogfish sticks are ideal for use in domestic food assistance programs.”

Some states expressly advise consumers that such foods are a good choice. The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, advises families that “fish sticks and other frozen, breaded fish products are safe for everyone to eat up to twice each week.”

If the breaded fish fillet is made from dogfish, though, that health advice is inaccurate, says Andrew Smith, Maine's state toxicologist.

Back at Portland Public Schools, the kitchen’s local fish vendor recently sent a sample of dogfish fillets to the school. The fillets were mixed in with a shipment of redfish, and kitchen employees prepared them both the same way. While the dogfish samples were not differentiated from the redfish to allow for a formal taste test — students commonly are asked to weigh in on new foods with smiley- or sad-faced ballots — Adams, the director of food services, says he didn’t hear anything negative. He hasn’t added dogfish to the regular menu yet, but he says if he does, he’ll likely offer it as fish nuggets, use it in fish tacos or simply prepare it like the redfish he already serves.