In December 2014, a handful of Disneyland tourists left the California theme park with more than just memories of Mickey Mouse and Space Mountain. They also left with the measles.

Within weeks, 125 cases were confirmed in the United States. Of the adults and kids infected, 110 lived in California — and nearly half had not been inoculated with the vaccine for mumps, measles and rubella (MMR), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ultimately, the outbreak resulted in 147 measles cases.

The disease spread because people had not been fully vaccinated, according to a 2015 analysis published in JAMA Pediatrics. The culprit was America’s growing anti-vaccination movement.

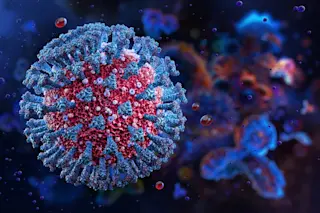

Measles is a highly infectious disease with symptoms including high fever and severe rash. In rare cases, complications can lead to encephalitis, a brain inflammation that causes seizures. Ninety percent of people exposed to someone with the virus will become ...