Coronavirus might be a new word for most people, but for a small cohort of scientists, that term has dominated their careers for decades. “I was writing reports about coronaviruses before it was cool,” jokes Frank Esper, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the Cleveland Clinic.

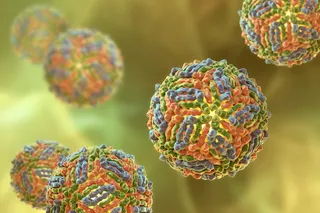

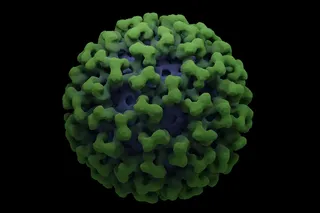

That’s because the virus causing the COVID-19 pandemic isn’t the coronavirus — it’s a coronavirus, meaning it belongs to a larger group of pathogens that share the name because they look similar to one another. A couple of other viruses in this category have made headlines in recent years after international outbreaks, namely SARS in 2003 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak that started in 2012.

Of the seven coronaviruses that have been circulating among humans, however, four of them just give someone a cold. Most people pick up at least one of these congestion-inducing viruses in their lifetime, and they’ve been ...