The New England Journal of Medicine recently published a short letter on two cases of vaccine-derived polio infection that arose in a German pediatric cancer ward three years ago. Two severely immunocompromised girls from the Middle East - one from Libya and the other from Saudi Arabia - had traveled with their families seeking specialized medical treatment in Germany.

A five-month old girl, known as Patient 1 in the article, required a bone marrow transplant for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), a rare inherited disorder (1). This condition achieved public notoriety in the case of the “bubble boy” David Vetter, a child who was insulated in sterile environments for over a decade from the time of infancy to shield him from exposure to potentially lethal infectious diseases. The two year old Patient 2 was seeking the same treatment for another rare immune disease, major histocompatibility complex class II deficiency, which is considered a variant of SCID.

Both conditions are genetic disorders that result in profound, life-threatening immunodeficiencies. Children are diagnosed at birth, typically after suffering from repeated bouts of ear and lung infections and multiple hospitalizations. The prognosis is poor, with patients generally dying in childhood or adolescence from overwhelming bacterial, viral, or fungal infections (2). A bone marrow transplant is the only therapy available.

A child is vaccinated while watching Jonas Salk, the creator of the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), administering the vaccine on television. Image: U.S. National Library of Medicine. Click for source.

In 2013, Patient 1 and Patient 2 had traveled to Germany to receive bone marrow transplants. As is common after receipt of this invasive procedure, both girls received routine medical workups to diagnose any latent or ongoing infections. Rather unexpectedly, however, poliovirus was detected in their stool samples, though both girls were free of any of the symptoms associated with polio infection. Notably, both children had previously been vaccinated with the oral polio vaccine as is common in their countries of origin.

Polio vaccines comes in two flavors. There is the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), administered via an intramuscular injection; in this vaccine the virus has been inactivated or “killed” by formalin, still maintaining much of its molecular structure which allows for the immune system to recognize the virus and develop protective antibodies.The other type of polio vaccine available is the oral polio vaccine (OPV), which is a “live” vaccine that contains a virus that has been weakened - attenuated in technical parlance - by growing multiple generations of the virus in cell cultures. With each new generation or “serial passage” of the virus in a culture of cells, the virus evolve, losing its virulence and ability to cause paralysis and death (3). Being a "live" vaccine, this weakened virus is still capable of replication. As such, administration of the OPV mimics infection with the actual poliovirus both in terms of its delivery by mouth and in the type of immunological protection that it generates against polio infection and disease. The vaccine is administered via two drops to the mouth and travels to the gut, where the weakened virus will replicate and induce an antibody response. These same antibodies will then be regenerated in the future should the body become exposed to the actual poliovirus.

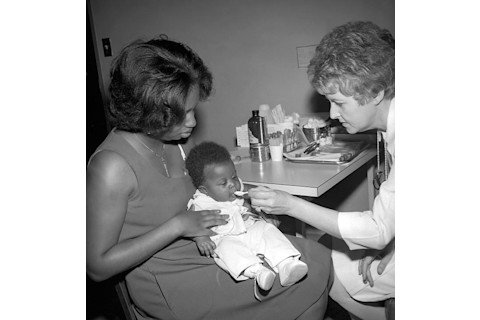

An infant receiving the oral polio vaccine (OPV) in Dekalb County, Georgia, 1977. Image: CDC/Meredith Hickson There are advantages to both vaccines but it is the oral vaccine to which we owe the massive success of global polio eradication over the past fifty-odd years. This vaccine does not require refrigeration or syringes and is thus easier to ship and utilize in resource-poor regions, making the OPV the vaccine of choice in developing countries (4). It is commonly used in mass vaccination campaigns that take place in underserved regions in the midst of a polio outbreak and it has served as our most effective weapon in the ongoing eradication of polio worldwide. But the oral vaccine does come with risks, and has been known to cause extremely rare cases of vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP) in recipients. These vaccine-associated viruses, borne of the attenuated poliovirus, have undergone genetic change as they replicate within the intestine after immunization and have subsequently regained their ability to cause neurological damage in a recipient of the OPV (5)(6). This situation is a one-time deal, only occurring in a single person who received the vaccine. There is also a related phenomenon of vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) infection in which the virus in the vaccine mutates and reverts to a “neurovirulent” phenotype capable of causing outbreaks (4). These VDPVs differ from VAPPs in that the new virus can circulate widely. VDPVs typically occur in regions where polio has been successfully eradicated and there is a subsequently low degree of vaccine coverage with some children vaccinated via OPV and others not (4). According to a publication by the CDC this past February, there are currently five countries - Guinea, Laos, Madagascar, Myanmar, and Ukraine - experiencing ongoing vaccine-derived polio outbreaks (7).It is well known that patients with immunodeficiencies, especially SCID, are at increased risk of excretion of vaccine-derived strains of polio. Without a functioning immune system to adequately respond to and control this weakened infection, these patients can harbor the virus for years, allowing the virus to mutate and serve as a source of reintroduction of polio into places where the virus has been eradicated. In 2013, five cases of VDPV infection were reported in India, every case attributed to a person diagnosed with an immunodeficiency - specifically, conditions in which their immune system is unable to produce antibodies (8). Though a rare event, these two cases of VDPV in young patients from the Middle East serve as a reminder that those with serious immunodeficiencies who have received the OPV should receive monitoring for the development of both paralytic polio as well as excretion of the virus. Such awareness is imperative to our continued successes in the extinction of a virus that has plagued mankind since the time of antiquityFrom the Body Horrors ArchivesVaccinating Against the Dark SideThe Eradication of Smallpox is a Blueprint for Polio's DemiseResourcesPolio cases could be wiped out within 12 months, says the WHO. Don't worry, I'm with you: WTH is up with VDPV vs. VAPP? Again, the WHO is here to help. References 1) A Schubert et al. (2016) Two Cases of Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Infection in an Oncology Ward. N Engl J Med. 374: 1296-1298 2) MA Saleem et al. (2000) Clinical course of patients with major histocompatibility complex class II deficiency. Arch Dis Child. 83: 356-359 3) Hanley KA et al. (2011)The double-edged sword: How evolution can make or break a live-attenuated virus vaccine. Evolution (N Y). 4(4): 635–643 4) OM Kew et al (2005) Vaccine-Derived Polioviruses and the Endgame Strategy for Global Polio Eradication. Annu. Rev. Microbiol.59: 587–635 5) CDC. (2015) Update on Vaccine-Derived Polioviruses — Worldwide, January 2014–March 2015. MMWR. 64(23): 640-646 6) WHO (February 2015) Fact Sheet: Vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP) and vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV). Accessed online on April 17, 2016 at http://www.who.int/immunization/diseases/poliomyelitis/endgame_objective2/oral_polio_vaccine/VAPPandcVDPVFactSheet-Feb2015.pdf 7) M Morales et al. (2016) Notes from the Field: Circulating Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Outbreaks — Five Countries, 2014–2015. MMWR. 65(05): 128–129 8) T Jacob John & VM Vashishtha. (2013) Eradicating poliomyelitis: India's journey from hyperendemic to polio-free status. Indian J Med Res. 137: 881–94