"I wish I were a rat," Frank Garofolo, a 56-year-old investment banker in Boston, said recently. Garofolo has diabetes, as do his mother, father, and brother; his sister died of it. He had just been told about an experiment at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City in which a plump lab rat lost more than half its intra-abdominal fat when it was exposed to a drug-and-light therapy usually used to kill tumors. A couple of years earlier, Garofolo had submitted to experimental surgery himself at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, during which a surgeon pulled chunks of ivory-colored fat out through small openings in his belly. Although the loss of 4½ pounds of intra-abdominal fat allowed Garofolo to go from a tight size 44 belt to a loose one, it didn't have the effect he so fervently desired—boosting his insulin sensitivity and lessening the severity of his diabetes—leaving him desperate enough to envy a rat.

More than fat anywhere else in the body—even more than overall obesity—intra-abdominal, or visceral, fat is associated with pernicious health effects in humans. A major effect is reduced sensitivity to insulin, the hormone that helps glucose enter the body's cells. Biologists lump visceral obesity (having a large midsection) with a cluster of other more obvious physiological abnormalities—high triglycerides, high blood pressure, high fasting blood sugar, and low HDLs (high-density lipoproteins, the so-called good cholesterol)—under the umbrella term metabolic syndrome; people with this condition are at increased risk for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

Studies have shown visceral obesity to be a risk factor on its own as well, a strong predictor of, among other things, heart attacks in young men, chronic heart failure in older people, high blood pressure in Japanese Americans, heart attacks in "well functioning" elderly women, and—the clincher, the coup de grease, if you will—of "all-cause mortality" in men. Having an excess of visceral fat has also been implicated in the development of Alzheimer's disease, colon cancer, gallstones, ovarian cystic disease, breast cancer, and sleep apnea.

"Visceral obesity," declares Philipp Scherer, a professor of cell biology and medicine at Albert Einstein and an expert on fat, "does seem to be truly evil."

Yet most people have never even heard of visceral fat. A survey released last year by the World Heart Federation concluded that most Americans are unaware that visceral fat is a leading risk factor for heart disease—even though, by one estimate, almost 46 percent of adult Americans have an excess of it. Moreover, the majority of physicians do not regularly check their patients' girth, which is the primary indicator of visceral obesity. "We are where cholesterol was in 1970 or blood pressure was in 1960," says obesity researcher Steven Smith of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge.

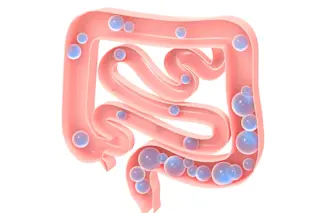

Visceral fat lies deep inside the abdomen, surrounding vital organs like the liver, heart, intestines, and kidneys, as well as hanging, in a separate double flap, off the ends of the stomach like an apron. In lean people, the flap, known as the omentum, is thin enough to be seen through (by someone in a position to have a look, that is). In obese people it may be inches thick, fused, and "hard like cake," according to Edward Mun, now director of bariatric surgery at Faulkner Hospital in Boston; he is the surgeon who removed part of Garofolo's omentum. Packed around the organs is another type of visceral fat, called mesenteric.

The abdominal region harbors still another kind of fat, which lies outside the abdominal wall, just under the skin. This subcutaneous, or peripheral, fat tends to be soft and flabby; you can pinch or grab it. It has two compartments, the deeper of which is thought, like visceral fat, to have negative effects on health. The superficial layer may cause cosmetic distress in women who get a buildup of it as they age, but from a medical perspective it is considered benign. Subcutaneous fat also appears outside the abdominal area, on the lower body—the hips, buttocks, and upper thighs. There it is not only benign but actually beneficial.

"Peripheral fat is, in reality, good fat," explains Osama Hamdy, director of the obesity clinic at the Joslin Diabetic Center.

Before menopause, women tend to have more good fat than men do. One interpretation holds that, through most of human evolution, visceral fat was useful for short-term storage—it accumulates quickly and is released quickly—for the benefit of male hunters who needed quick access to energy. Subcutaneous fat, in contrast, was meant for long-term energy storage, for the benefit of the (often female) gatherers who had to wait a long time between meals. Subcutaneous fat is less active metabolically than visceral fat. "It's like a big bucket," Smith says. "It locks the fat in." Put another way, it keeps accepting excess caloric energy that might otherwise end up in the abdomen. Jean-Pierre Després, director of research in cardiology at the Laval Hospital Research Center in Quebec City, calls subcutaneous fat "an expandable metabolic sink."

Compared with women, men not only have "a smaller gluteofemoral [butt-thigh] bucket," notes Smith, but they also have twice as much visceral fat, the stereotypical beer belly. (Approaching menopause, women start to catch up.) The belly may feel hard to the touch instead of soft, the visceral fat pushing up against the muscles of the abdominal wall. Health profiles reflect this sexual dimorphism: Men tend to be less insulin sensitive than women.

One of the first to make this link was Jean Vague, a professor on the faculty of medicine at the University of Marseille. In 1956 he recognized this male-pattern obesity—also called android obesity—and observed that it leads to "metabolic disturbances," including diabetes. Vague was far ahead of his time. "Obesity wasn't a big deal in the '50s," Smith says. "We were dealing with polio." Nowadays a person with android obesity would be called an "apple," while a person with gynoid obesity ("with lower-body predominance," Vague wrote) would be a "pear." As anyone who has read a fitness magazine knows, apples are bad, pears are good.