Last week Luke Jostins (soon to be Dr. Luke Jostins) published an interesting paper in Nature. To be fair, this paper has an extensive author list, but from what I am to understand this is the fruit of the first author's Ph.D. project. In any case, you may know Luke because I have used his loess curve on hominin encephalization for years. His bread & butter is statistical genetics, and it shows in this Nature paper. God knows how he managed to cram so much density into ~5.5 pages of plain text. Luke is also a contributor to Genomes Unzipped, and has put up a post over there on one implication of the paper, Dozens of new IBD genes, but can they predict disease? The short answer is that for individual prediction complex traits are going to be a hard haul over the long term.* They are subject to what ...

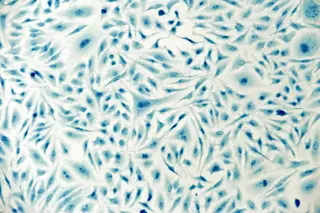

Inflammatory bowel syndrome is nature's side effect

Explore groundbreaking insights into the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease through extensive genome-wide studies.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe