For the first time researchers have sequenced the complete genome of a cancer cell, and they say the process turned up eight previously unknown genetic mutations that played a role in the patient's terminal leukemia. As it gets cheaper and easier to decode entire genomes, as opposed to just checking "usual suspect" stretches of DNA, doctors hope to decode the genomes of many different types of cancer. Eventually, researchers say cheap techniques may allow doctors to study the cancer genomes of individual patients. Lead researcher Richard Wilson

said he hoped that in 5 to 20 years, decoding a patient’s cancer genome would consist of dropping a spot of blood onto a chip that slides into a desktop computer and getting back a report that suggests which drugs will work best.“That’s personalized genomics, personalized medicine in a box,” he said. “It’s holy grail sort of stuff, but I think it’s not out of the realm of possibility” [The New York Times].

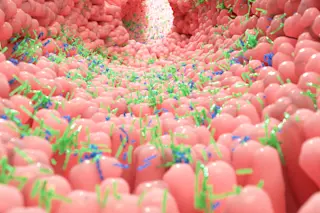

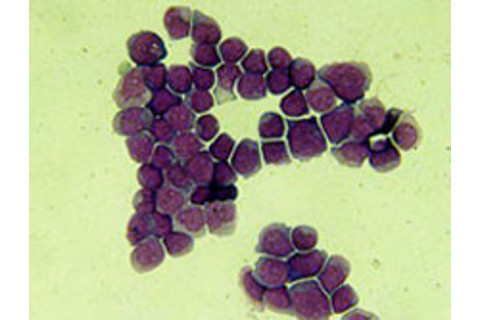

In the study, published in Nature [subscription required], researchers compared tumor cells and normal, healthy cells all donated from a woman who died of leukemia in her 50s. The comparison allowed them to identify mutations that occurred only in the cancer cells.

None of the researchers knew what to expect for the number of mutated genes in the cancerous cells. “We were flying blind,” says [study coauthor Timothy] Ley [Science News].

They finally identified 10 significant mutations that appeared to encourage tumor growth and allow the cells to fight off chemotherapy; eight of those mutations had never before been linked to leukemia. Researchers also studied tumor samples from 187 other patients with the same form of leukemia, called acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), but found that none had the eight newly discovered mutations.

Dr Richard Wilson said: "This suggests that there is a tremendous amount of genetic diversity in cancer, even in this one disease. There are probably many, many ways to mutate a small number of genes to get the same result, and we're only looking at the tip of the iceberg in terms of identifying the combinations of genetic mutations that can lead to AML" [BBC News].

However, that daunting variety doesn't mean that a new drug would have to be developed for each individual patient, said Wilson.

“Ultimately, one signal tells the cell to grow, grow, grow,” he said. “There has to be something in common. It’s that commonality we’ll find that will tell us what treatment will be the most powerful” [The New York Times].

Related Content: 80beats: Get Your Genome Sequenced--Now 95% Off 80beats: New Test Could Allow "Real Time" Tracking of Cancer TumorsImage: Timothy Ley