The pith: there are differences between populations on genes which result in "novelty seeking." These differences can be traced to migration out of Africa, and can't be explained as an artifact of random genetic drift.

I'm not going to lie, when I first saw the headline "Out of Africa migration selected novelty-seeking genes", I was a little worried. My immediate assumption was that a new paper on correlations between dopamine receptor genes, behavior genetics, and geographical variation had some out. I was right! But my worry was motivated by the fact that this would just be another in a long line of research which pushed the same result without adding anything new to the body of evidence. Let me be clear: there are decades of very robust evidence that much of the variation in human behavior we see around us is heritable. That the variation in our psychological dispositions, from intelligence to schizophrenia, is substantially explained by who our biological parents are. This is clear when you look at adoption studies which show a strong concordance between biological parents and biological children on many metrics as adults, as opposed to the parents who raised the children. This doesn't mean that environment doesn't matter, but I believe we tend to underweight genetics in individual outcomes in our contemporary Zeitgeist, just as we may have overweighted it in the past. At this point some of you may be wondering, "what, I hear about genes for [fill in the blank] constantly!" So why am I saying we underweight genetics? I think there's a disjunction between the fixation that the public (and therefore the popular press) has on a specific biophysical candidate gene which is given almost magical powers of causal necessity and the more abstract and diffuse statistical genetic reality of correlations between parents and offspring whose effects seem to be distributed diffusely across the genome. The latter is a robust and ubiquitous phenomenon, but because it is not possible to frame the narrative as a "gene for X" it lacks power. In contrast, when you have a powerful gene of large effect whose variation in state has a concrete and comprehensible outcome the narrative is clear, precise, and distinct. There's an unfortunate problem with this though:

quite often the narrative is wrong because it is not robust.

It won't be replicated and stand the test of time.

The example of the "language gene," FOXP2, is illustrative of the issues I'm pointing to in the most broad of terms. As a matter of fact FOXP2 is a much better candidate for being the "language gene" than is usually the case for the gene for X, but ultimately it is probably not alway useful to term FOXP2 the language gene when the faculty for speech is such a complex trait subject to many biological pathways. The putative "God gene" was a much worse case of a gene for X, and probably a good example of the problem I'm talking about. There's a pretty robust body of evidence that religiosity has a heritable component, but there isn't much evidence for a gene for belief in God. What does all this have to do with dopamine receptors and novelty? The DRD4 locus has been implicated in a lot of behavior genetic variation, and dopamine receptor genes are often pointed to as "master controllers" of a sort for various aspects of personality and life outcomes. Dopamine as a neurochemical has myriad functions, so variation in its production controlled by genetics is a natural candidate of interest for researchers. The problem is that the nature of this sort of statistical and sexy science is that there's going to be a natural gravitation toward significant results which later turn out to be false positives. Before moving on, I do want to reiterate that as a gene for X the dopamine receptor loci are much better set of candidates than the "God gene," but here the devil is in the details. Let's see what the argument in the paper which triggered The New Scientist piece is. Novelty-seeking DRD4 polymorphisms are associated with human migration distance out-of-Africa after controlling for neutral population gene structure:

Numerous lines of evidence suggest that Homo sapiens evolved as a distinct species in Africa by 150,000 years before the present (BP) and began major migrations out-of-Africa ∼50,000 BP. By 20,000 BP, our species had effectively colonized the entire Old World, and by 12,000 BP H. sapiens had a global distribution. We propose that this rapid migration into new habitats selected for individuals with low reactivity to novel stressors. Certain dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4) polymorphisms are associated with low neuronal reactivity and increased exploratory behavior, novelty seeking, and risk taking, collectively considered novelty-seeking trait (NS). One previous report...demonstrated a correlation between migratory distance and the seven-repeat (7R) VNTR DRD4 allele at exon 3 for human populations. This study, however, failed to account for neutral genetic processes (drift and admixture) that might create such a correlation in the absence of natural selection. Furthermore, additional loci surrounding DRD4 are now recognized to influence NS. Herein we account for neutral genetic structure by modeling the nonindependence of neutral allele frequencies between human populations. We retest the DRD4 exon 3 alleles, and also test two other loci near DRD4 that are associated with NS. We conclude there is an association between migratory distance and DRD4 exon 3 2R and 7R alleles that cannot be accounted for by neutral genetic processes alone.

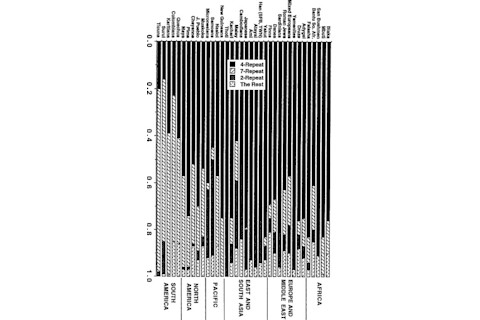

I am impressed by the extent to which the authors touched all the bases in this paper. As a case of how natural biases work you probably wouldn't be reading this post if it was just another paper which was going to go into the memory whole and become a small C.V.-builder. What's the point of reading and reviewing papers which don't present anything new? So what's new here? First, let's review the curious case of DRD4. It's a gene, and like any gene there are different variants depending on the region you're looking at and the type of variation you're looking at. The second is important because often I'm talking about single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), a change in the bases at a specific position, but the most relevant type of variation for this locus are actually tandem repeats. These repeats vary in number, so you have alleles of different lengths. ~90% of the variation in populations surveyed falls into the classes of 2, 4, and, 7 repeat alleles within exon 3 of the gene (an exon is a coding region), termed 2R, 4R, and 7R. The 4R repeat value is presumably ancestral, and the most common variant world wide, while the 7R variant is common in the New World, and the 2R in East Asia. You can't just get VNTR polymorphism from the HGDP Browser last I checked so I yanked the bar plot you see above from the 1996 paper where the variation on these polymorphisms was originally assayed (definitely in the days before R!). There's a clear limitation on the population coverage in this paper because all the new-fangled genomics has been focusing on SNPs first (though you see papers on copy number variation now and then). This issue should be eliminated with the ubiquity of full genomes, but that's for the future. As you can see there's a tendency for the 4R allele to be modal in Africa, and decrease in frequency as you move away. 2R is more common in East Asia, while 7R is very common among some tribes in the New World. Why? This is where "novelty seeking" (NS) comes into play. One simple model is that those with NS alleles are more likely to migrate. So the rank order would be 4R > 2R > 7R. So instead of temporal natural selection you are talking about spatial natural selection. There are several problems with this model, but one of the most immediate ones is that immigrants to the USA from Europe and Asia don't seem to exhibit the pattern you'd expect, an enrichment of 7R/2R vs. 4R. A second bigger problem is that when you see geographic distributions they may reflect random events of population history due to stochastic fluctuations in gene frequency. In plain English a series of population bottlenecks can result in gradients of allele frequency due to simple genetic drift + population history. Populations with more recent common ancestors share more genetic drift history than those more distantly related. But let's back up for a moment. What's going on with the repeat alleles and behavior? Psychology and neuroscience aren't my thing, so let me quote from the paper:

7R and 2R alleles are associated with a partial loss of DRD4-mediated prefrontal inhibition because of blunted second messenger response. Compared with the 4R, the 2R and 7R alleles result in 40 and 80% reduction in intracellular second messenger response, respectively.... Promoter polymorphisms, including a −521 C/T single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and a 120-bp tandem duplication located 1.2 kilo-bp upstream of the initiation codon, are associated with similar neurophysiologic downstream effects as 2R and 7R exon 3 VNTR alleles...There is a well-supported correlation between the DRD4 7R, 2R, 120-bp promoter duplication, and −521 C/T SNP and the personality trait novelty seeking (NS)...High NS individuals are considered exploratory, impulsive, excitable, quick-tempered, and extravagant, whereas low NS individuals tend to be rigid, prudent, stoic, reflective, staid, and slow-tempered...

As you can see there are two other genetic variants, a SNP and a duplication region, on DRD4 that they're looking at in this paper in addition to the repeats which are the focus of the research. These are the only other variants which were found in the literature and were assessed in 15 or more populations in their data set. Note that the variation in the genes are associated with biophysical changes on the molecular scale, as well as the personality differences.

At this point we need to get the meat of the paper:

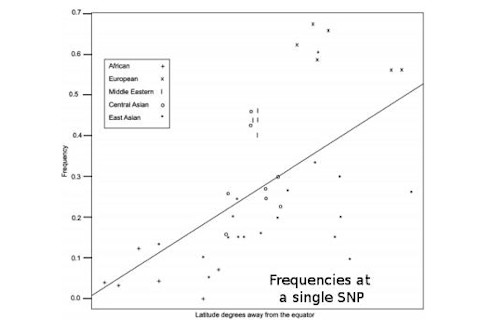

they propose to control for population history/structure in the distribution of DRD4 alleles

. The problem is illustrated in the plot to the left. You see the allele frequencies at a single SNP as a function of distance from the equator. This could be a signal of selection on a functional variant since the change in the environmental parameter and change in the allele frequencies are correlated. But the symbols which represent the population aggregate proportions of the allele also indicate the region of origin of the samples. What is clearly evident is that there is clustering dependent upon the region of origin. So you have a set of points which are used to generate a correlation...but those points are clearly not independent. They cluster together in units defined by geographic origin. Why? One plausible explanation is that populations near to each other share common evolutionary history, and so are perturbed in the same direction of allele frequencies by drift dynamics. In other words, shared evolutionary history produces the result of correlation between allele frequency and geographic gradients, because geographic gradients determine evolutionary history! The proposition that DRD4 alleles vary due to migration may suffer from this problem. To correct for this the authors start out with the "serial bottleneck" model of expansion out of Africa. So all human populations can be traced by the San through a sequence of founders. Obviously New World groups would be separated by the greatest number of founding events, East Asians and Oceanians somewhat less, and Europeans and Middle Easterners the least. There are some immediate problems I have with this, but I'll hit that later. With this in mind they constructed a linear model where you have a set of variables which predict an outcome. In their case the predictors would be the frequencies of the alleles at DRD4, and the outcome would be migration (distance from the point of origin with their model of serial bottlenecks). They generated a correlation structure using genetic distances from the literature. The correlation structure is a proxy for the phylogenetic tree which defines the set of relationships which characterize the evolutionary history of these populations. In other words you expect correlations in gene frequencies from populations which are relatively closely related as opposed to those which are distantly related. As a check on this they took 400 pre-validated neutral alleles, not subject to natural selection and so ancestrally informative, and put them through their models controlling for structure and not controlling for structure. The average slope which measures the relationship between migration distance and the genes in question was zero for the neutral markers. In other words migration distance wasn't predicated by them. But there was a huge range of variance of the slope of the regression (which measures the correlation, so that a slope near 1 is well correlated and 0 is uncorrelated). Remember, randomly there will be a lot of different relationships. Here's the important point: the variation in the slope across the neutral genes decreased a lot once you controlled for the genetic relationships between the populations. They still average out to zero, because these are neutral genes, but a lot of signals thrown up by genetic drift producing between region population structure were reduced once you took into account between region population structure as measured by their proxy of genetic distance.

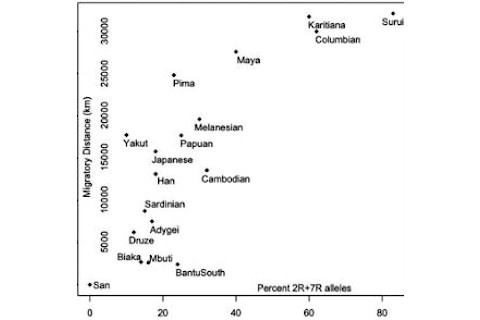

The major result is shown to the left. This is a plot which illustrates the relationship between the proportion of 2R + 7R alleles and migration distance

controlled for population structure.

The relationship still holds as you can see for these alleles to a statistically significant degree (just below the 0.05 threshold). On the other hand the relationship does not hold for the other two variants in the promoter region. This is interesting because all of these variants have been shown to have an outcome on dopamine pathways in terms of correlations on the molecular genetic scale as well as in some behavior genetic studies. But

in this case one can not infer that there is a relationship between migration and genetic variation on DRD4 on the non-repeat variants.

What to make of all this? I have to note what when I got to the discussion of this paper I actually went back and reread their introduction and results because its tone was so cautious and equivocal that I wasn't sure if they actually had positive results at all, and if I'd just seen it by mistake. The authors make some very criticisms of naive inferences of evolutionary importance to behavior genetically interesting alleles without taking into account phylogenetics. Additionally they seem to be implying that one should be skeptical of behavior genetics results which don't often cohere together as a whole. They point out that many of the behavior genetic results are biased toward people with psychiatric illnesses and there's just not that much analysis of normal human variation because of the nature of the funding. And yet after the stringent controls which they applied the 7R/2R variants still seem correlated with migration, so they argue that this warrants further investigation. Two critiques I'd immediately make is the nature of their population coverage as well as their model of demographic history. The population coverage they could not control; only some groups have been typed for VNTR variation on DRD4. But I think it should make us wary of simply taking a p-value below 0.05 at face value. Who knows how the p-value might change as one increases coverage? It's a good start, but more research needs to be done, as they properly admit in the discussion. More important for me though is the fact that they worked within the serial bottleneck out of Africa migration framework. This may still work...but perhaps it may not. Our understanding of the human past and the nature of the emergence of modernity humanity is somewhat in flux now, so one of the solid foundations which are simply assumed as givens in this paper has become a lot less solid over the past few years. Some of the migrations which they hypothesize I simply don't even believe. For example: Druze → Cambodian → Papuan → Melanesian. I can see the plausibility for this case, but Melanesians have Austronesian admixture, and Cambodians are I believe in large part derived from a migration of farmers from southern China. There's reticulation and back migrations which are going to confound the idea of a serial bottleneck, even assuming a simple out of Africa event. The authors do acknowledge that they're underestimating migration distance, but I wonder how robust their results would be to further refinements? Additionally, the serial bottleneck out of Africa to me is too redolent of the thesis from ~10 years ago that most extant genetic variation across populations can be traced back to the distributions circa 20,000 years before the present. I don't know if this is true anymore. Rather, we may have a palimpsest where in many regions there has been a massive overlay due to the expansion of farmers. Finally, a lot of the hypothesized evolutionary pressures resulting in allele frequency differences seem ad hoc or post facto. We know from behavior genetics that the "long" and "short" repeats, 7R and 2R, lead to novelty seeking. How does that map onto the cultures we see? And how did long term pressures shape those allele frequencies? The original research on 7R and 2R suggested that spatial selection, where migrants were self-selected, can't explain it because of modern immigration patterns...but how applicable is that to the past?* There are lots of questions here. All in all, this is an interesting paper. It has moved the "needle" in my estimation that DRD4 has been the target of selection. But in terms of specifics I've got a lot of questions. Citation:

Matthews LJ, & Butler PM (2011). Novelty-seeking DRD4 polymorphisms are associated with human migration distance out-of-Africa after controlling for neutral population gene structure. American journal of physical anthropology PMID: 21469077

* Please note,

The New Scientist summary is kind of misleading on this point.

They don't believe that selection operated upon migration, rather, selection operated upon populations which had migrated due to new environments.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons